A massive mat of seaweed, hundreds of miles long, is currently floating toward the Caribbean coast of Mexico. The Sargassum threatens to coat over 180 miles of beaches there, washing up along popular destinations like Tulum. As it advances, the once clear blue waters are turning brown and the algae’s decay sickens the fresh, salty air with a rotten egg smell. Desperate to keep tourists coming, hotel owners are spending up to $47,000 a month to clean up the mess.

New satellite data reveals that the “great Atlantic Sargassum belt” extends from the west coast of Africa to the Gulf of Mexico. This yearly bloom might be here to stay, according to a new study, published Thursday in Science. “This is the largest belt of seaweed in the world,” says the study’s lead author, Mengqiu Wang, an oceanographer at the University of South Florida.

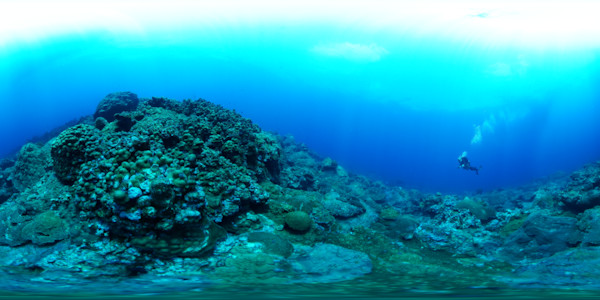

Sargassum is a brown seaweed with large, leaf-like structures and gas-filled “berries,” which allow it to stay afloat. It is, unsurprisingly, a defining feature of the Sargasso Sea in the northern Atlantic ocean. Sargassum mats are important habit for fish, birds, turtles and crustaceans. A lot of prized fish we love to eat—including mahi mahi and amberjack—use these tangled marine vines as a place to raise their young. “In open waters, it’s a good thing,” says Wang. “But when it washes onto the coast, it becomes a coastal nuisance.” Or worse.

Not only does Sargassum smell and look gross, the piles of dead seaweed can harm humans and animals. Hydrogen sulfide—the stuff that makes that rotten egg odor—can also irritate the lungs, especially for people with conditions like asthma. As the seaweed rots in coastal waters, decomposer microbes use up oxygen, causing marine animals to suffocate. Hydrogen sulfide and ammonium, chemicals released during decay, also poison aquatic life. A recent study reported that organisms of 78 species, mostly fish and crustaceans, died during a 2018 Sargassum tide in Mexico. It’s also washed up on Carribean islands, Florida beaches, and Africa’s west coast.

After hearing numerous reports of Sargassum washing up, Wang wanted to see if she could find where all this seaweed was coming from. She used data collected on NASA satellites to visualize the seaweed across the Atlantic. Because the chlorophyll in the seaweed reflects infrared light, it shows up clearly in the satellite sensors.

The resulting maps shown an obvious and growing presence since 2011, with the Sargassum clumped together across a massive belt in the Atlantic. In 2018, this belt contained over 20 million metric tons of seaweed, the study estimates.

The scientists also investigated potential causes of the seaweed bloom. They looked at how different factors correlated with the growth of the brown algae, including sea surface temperatures and nutrient levels. Based on this analysis, it seems that increased nutrients leaching into the ocean are probably to blame, especially those coming from Brazil.

In recent years, deforestation and agriculture have intensified in the Amazon, leading to more nitrogen and phosphorus in the Amazon river, which is then dumped into the ocean. In addition, there’s a major upwelling site off the coast of Africa, where nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean rises to the surface. Using a computer simulation, Wang found that ocean currents could be transporting these nutrients into a belt along the Atlantic, matching up with where the Sargassum is blooming. “It’s very rare to see a huge pattern like this in open water,” she says.

The seaweed mat still has its secrets. Wang adds that while her work shows a hypothesis for its formation, other factors could be at play. We don’t know how global warming and associated ocean acidification might be affecting the algae’s growth, for example.

What does seem clear is that as long as we keep feeding the seaweed, it’ll continue to bloom and muck up coastal waters. Deforestation in the Amazon is only speeding up. As of May, a soccer field-size plot of rainforest is cleared every minute. “If we don’t change anything, [the seaweed belt] will stick around,” says Wang.