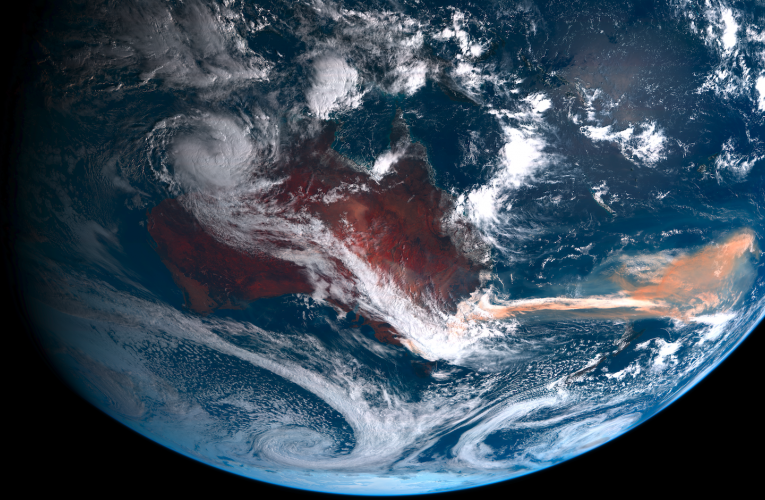

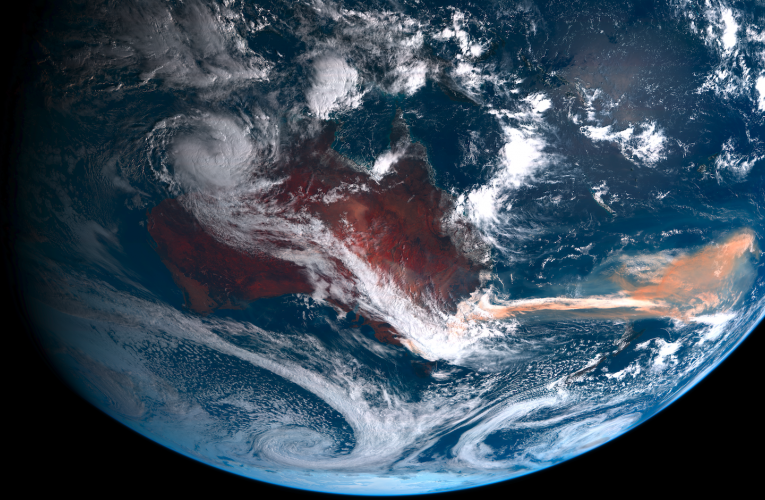

The wildfires of 2019 and 2020 in Australia burned an area of eucalyptus forest larger than the state of West Virginia. They released more carbon than the entire country produced in 2018, sending plumes of smoke 20 miles into the air and creating an atmospheric eddy the size of Montana.

Then, that smoke did something even more unexpected, according to new research published today in Nature: it fell on the Southern Ocean to the east of Australia, sparking a months-long algal bloom. The bloom spanned thousands of miles, with uncertain effects on both marine life and global emissions—and illustrated how we’ve only just begun to understand the global ripples of climate change.

“When you see the images of the wildfires, the environmental impact of these fires is pretty obvious on local ecosystems,” says Nicolas Cassar, a biogeochemist at Duke University, and an author on the paper. “The surprise to me is how these wildfires can have an impact on ocean ecosystems thousands of kilometers away.”

Algae blooms are short-lived population explosions of tiny sea plants. They usually happen when a waterway is flooded with some kind of critical, scarce nutrient. Algae gobble up all of that food, grow rapidly, and then die off. As they decay, they suck oxygen out of the water.

Public health officials have warned about the possibility of algal blooms after wildfires in inland North America, since fires can leave streams, lakes, and reservoirs choked with ash and dead plants. And once algae does bloom in that nutrient-rich soup, it can be deadly: over the past week, three dogs appear to have died along the Columbia River in Washington after playing in algal water.

But this is one of the first times that an algae explosion in the open ocean has been connected to a wildfire. At sea, algae can poison other organisms directly by pumping out toxins—often called “red tide”—or it can choke marine life to death as it rots. Often, algae blooms are caused by pollution from fertilizers, as in the dead zone at the mouth of the Mississippi River. But a record-setting toxic bloom on the West Coast in 2015 was caused by unusually warm waters, while a 1997 event that smothered coral reefs was linked to wildfires in Indonesia.

In this case, researchers think the growth was driven by iron in the smoke. The Southern Ocean contains many of the other essential minerals that algae need to grow, but iron is comparatively scarce. What little exists comes from deep in the ocean, melting ice, or dust falling on the sea’s surface. “Delivery of [iron] to these waters is believed to be an essential driver of” algae growth, the authors write.

[Related: Maggots and algae could be the sustainable snacks of the future]

Satellite images of the smoke showed that soot fell on an area larger than the entire continent of Australia, and was particularly heavy in two spots: the ocean to the south of Australia, and thousands of miles to the east, off the coast of South America.

From October to April, algae growth took off in that region, with blooms following peaks in soot.

“The scale is substantial,” says Weiyi Tang, one of the study’s lead authors, and a biogeochemist at Princeton University. “The area that was affected exceeds the area of Australia.”

The blooms were so large that the authors estimate that they ended up absorbing the equivalent of 50 to 150 percent of the carbon released by the actual fires. That could mean that the algal blooms actually offset the fires’ impact on the climate.

“The holy grail is, how much did it offset?” says Cassar. “But we don’t know.”

If algae sits on the surface, that carbon will go right back into the atmosphere. But if it sinks, the carbon will become locked up on the seafloor.

To figure that out, scientists would need to travel to the site of the bloom as it was happening, and measure how much gunk was actually falling down to the seafloor—and Tang and Cassar hope to be able to mount that kind of rapid response in the future.

It’s still not clear what the blooms meant for marine life throughout the Southern Ocean, or around the world. According to research published earlier this year, the region is already home to some of the biggest algae blooms on the planet—and if they become more common with climate change, those plants may end up soaking up vital nutrients that would otherwise fertilize other parts of the ocean.

“The Southern Ocean is a really important part of the world,” says Cassar. “It has a disproportionate influence on our climate. A huge amount of the anthropogenic heat is in the Southern Ocean, and the anthropogenic carbon. So changes to it can have ramifications for our global climate.”

But the authors also note that Australia has had wildfires before, yet hasn’t seen this kind of massive bloom. That may be because the fires were so enormous, or because they lined up with some other environmental cycle, like sunny weather or the right wind conditions.

“The ocean system had to have the perfect conditions to be responding to the higher supply of aerosols,” Tang says.

It could be possible that conditions will line up in similar ways elsewhere in the world. “There might be other places responding to the wildfires,” says Tang. “We’re really trying to take a better look.” Oceans off the coast of North America, Siberia, Africa, and the Amazon may all be changing in ways that are completely unknown.