This article was originally featured on Task & Purpose.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of War and Climate Week, a series of stories exploring how the U.S. military is coping with extreme weather, sea-level rise, and a warming globe.

Forget what you’ve seen in movies: flying low and slow in large fixed-wing aircraft is tough to do. It is even more difficult while flying through mountains, where the weather is unpredictable and the terrain forbidding. Now add to the picture crowded airspace where you might collide with another aircraft if you are not careful. Oh, and by the way, half the airspace is filled with smoke and there is a wildfire raging off your wingtip with flames reaching over 100 feet high.

That kind of delicate situation is why airmen with years of experience consider aerial firefighting to be one of their most challenging missions outside of combat. But it is a mission that members of the Air Force’s 302nd Airlift Wing often find themselves on when government officials need extra hands to contain the devastating fires that spark across the country all year round.

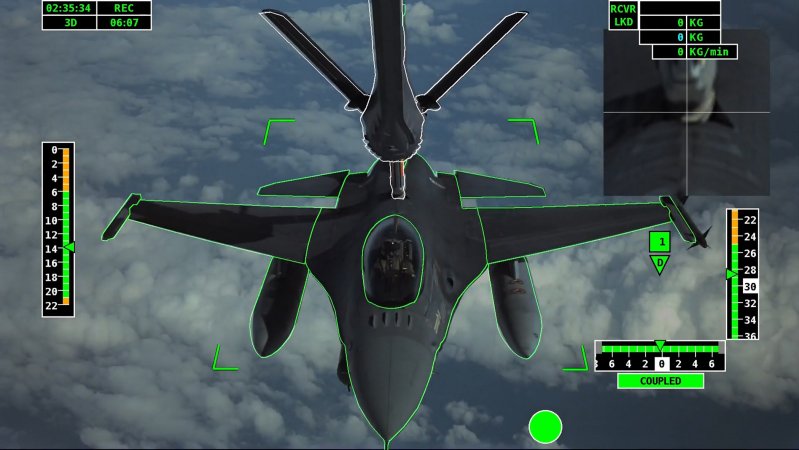

“It does require all six of us on an H-model C-130 to work together, to be supremely proficient in the aircraft and really in sync,” said Lt. Col. Richard Pantusa, chief of aerial firefighting for the 302nd. The wing flies the C-130 Hercules, a highly-adaptable four-engine transport plane that can be modified to land on snow, shoot 105mm cannon rounds, or fly into hurricanes. But even the C-130 needs its crew on point to safely execute a low, slow aerial firefighting mission.

“150 to 200 feet above the ground, going 120 knots or so … those parameters are challenging,” Pantusa said. 120 knots is equivalent to about 138 miles per hour. In that situation, pilots must be laser-focused to make sure the aircraft is at the proper speed and altitude and headed in the right direction and in the correct configuration to prevent drag. The co-pilot meanwhile is busy looking out for hazards such as power lines, birds or smoke which can seemingly come out of nowhere so close to the ground. The navigator keeps an eye out for terrain hazards and makes sure the aircraft can get down to the target area; the engineer monitors the aircraft to make sure it is performing well and the loadmasters in the back operate the Modular Airborne Firefighting System, the 11,000-pound system of metal tubes and tanks that drops 3,000 gallons of fire retardant in less than five seconds.

“They all have a job to do and it’s all critical in nature,” Pantusa said.

But this is a military aircrew we’re talking about, right? Aren’t they trained to do this sort of thing in their sleep while getting shot at by rocket-propelled grenades? Not quite. While the crews qualified to fly aerial firefighting missions are well-trained to do the job, it is not their primary mission. The 302nd is a combat-ready tactical airlift and airdrop unit, and tactical airlift is a different ballgame from aerial firefighting.

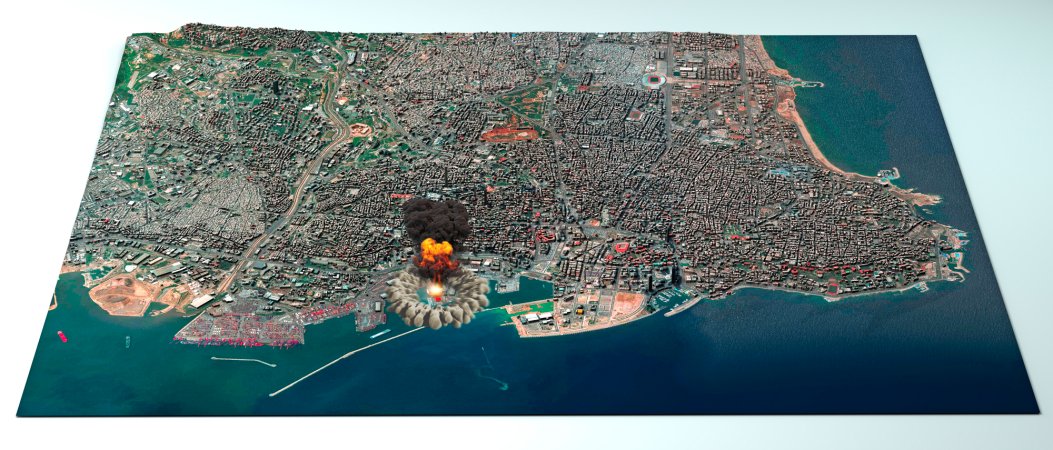

There’s a good reason why these combat-ready aircrews have to switch up their tactics to help with wildfires at home: the Laguna Fire of September 1970, when a 175,000-acre wildfire swept through southern California, killing 16 people and destroying nearly 400 buildings. In response to the disaster, Congress created the MAFFS program, ordering the U.S. Forest Service to provide the MAFFS system and the fire retardant while the Department of Defense provides the aircraft, crews and maintainers to fly the mission.

Though this article is about Air Force crews, most of the country’s aerial firefighting is carried out by a large fleet of civilian contractors such as 10 Tanker and Coulson Aviation. The MAFFS program authorized the Air Force to set up eight C-130s and their crews to be ready to help with the firefighting mission in case the civilian contractor fleet was stretched too thin by an intense fire season. One such season was June 2021, when seven out of 10 Federal Emergency Management Agency regions were experiencing large wildfire activity requiring federal assistance.

“The contract fleet was stretched to the limits,” Pantusa said. “We’re the surge force, so when we’re called in to surge, that’s what we do.”

The 302nd Airlift Wing is one of four wings in the Air Force trained and equipped to do the MAFFS mission, though the 302nd is the only unit in the Air Force Reserves that can do so. The others are all Air National Guard: California’s 146th Airlift Wing, Nevada’s 152nd Airlift Wing and Wyoming’s 153rd Airlift Wing. Each wing has two C-130s and the necessary crews trained to answer the National Interagency Fire Center’s call at a moment’s notice.

“We have 48 hours from the time they notify us to get wherever they need us to go,” Pantusa said.

Since Air Force crews like those from the 302nd are the backup, the scene is already lively when they arrive. The airspace over a fire is usually crowded with other aircraft lining up to drop retardant to help crews working on the ground. To make things more complicated, there might also be Air Force RC-26 surveillance planes collecting intelligence on the fires; helicopters scooping water for direct attacks on the fire, and other manned or unmanned planes providing support and coordination to the rest of the effort. Though the aircraft come from all over the region and even all over the world, they spend time beforehand brushing up on the same standard tactics and procedures to minimize the chance of an accident and to make the operation as efficient as possible.

“It is like a NATO operation,” in terms of getting a large number of air crews from a wide range of backgrounds on the same page, Pantusa said.

When an Air Force C-130 takes off to fight fires, it is at the disposal of the incident commander, the firefighter on the ground who comes up with the strategy for containing and knocking down the fire. Despite what it might look like from pictures, the purpose of a MAFFS mission is not to put out a fire by dropping fire retardant directly onto it. Instead, the purpose of a MAFFS mission is to drop the retardant on the place where the incident commander does not want the fire to spread, so that the ground teams can more easily contain it. After all, it’s called fire retardant, meaning to prevent or inhibit, not fire putter-outer.

“We don’t put fires out, we slow the rate of spread and cool down fire as it progresses so ground forces can get ahead of it,” Pantusa said.

The reason C-130s and other aircraft have to fly so slow and low to drop fire retardant is because it is essentially “just enhanced water,” which needs to fall to the ground vertically like rain in order to effectively coat the plants, logs and other flammable material below, the airman said.

MAFFS is an impressive system: it can drop 3,000 gallons of fire retardant weighing about 28,000 pounds through a tube out the back of the aircraft in less than five seconds. The retardant, also called “slurry” or “mud,” is 80 to 85% water and 10 to 15% ammonium sulfate, a jelling agent, and red coloring, according to the Air Force. Why red? Because it helps pilots see where they dropped previous loads. While 3,000 gallons sounds like a lot, it can cover an area only a quarter-mile long and 60 feet wide. That’s a good amount of ground, but sometimes an incident commander wants several miles covered as he or she sets up a line of containment. When that happens, “we get into a loop where we launch, drop, refill and do it again,” Pantusa said.

The maintenance crews waiting at the flightline are trained like a NASCAR pit crew, the officer explained: the plane can land, take on a fresh supply of fire retardant and take off again in as little as 15 minutes. A hard day’s work might involve six to eight drops, but crews have performed as many as 15 in a single day. Remember, each of those drops involves an intense amount of concentration to pull off, but it also requires a significant amount of flexibility.

“All it takes is the wind to shift 90 degrees and everything we’re working on can be called off,” Pantusa said. For example, if smoke blows over the drop zone, it might limit visibility, which makes it too dangerous for MAFFS crews to fly into. Luckily they do not fly alone: it’s standard procedure for C-130s and other firefighting aircraft to follow a smaller lead plane, often flown by federal or state pilots, which makes sure the conditions and wind speed are good and that the escape route is clear for the aircraft to climb back up.

“They show us where the retardant goes, we fly right behind him,” Pantusa said. “They help before you take a 150,000-pound aircraft through.”

The wing rotates out crews every week to avoid burnout, the officer explained. But fighting wildfires is still a demanding task, especially last year when all eight of the military’s MAFFS aircraft helped fight the Dixie fire. The largest single wildfire in California history, the Dixie fire covered 963,300 acres and destroyed 1,300 buildings in northern California last summer.

“We found ourselves in the situation of kind of scrambling to put together another month worth of a second crew that we didn’t know we were going to need,” Lt. Col. Patrick McKelvey, a C-130 pilot with the Nevada Air National Guard, told Air Force Magazine last year. A former Navy F/A-18 fighter pilot, McKelvey said dropping fire retardant is as challenging as a nighttime carrier landing.

“Every situation we go into is unique … You’ve never flown that line. You have absolutely no idea what you’re getting into,” he said. “And we’re going down to 150 feet and doing it far slower than we would normally do an airdrop because of the way the retardant comes out of the airplane. So, it’s lower, you’re heavier at max gross weight, you’re using far more power. It’s hot, you’re at high altitude up in the mountains, canyons, obstacles, trees. Next to flying around the aircraft carrier at night, this is probably some of the most high-risk flying I’ve ever done.”

The fires could get worse in future summers. Multiple studies show that climate change is making wildfires season longer and more devastating, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Part of the reason why the season is longer is due to warmer springs, longer summer dry seasons, and drier soils and vegetation, the EPA said.

“Climate change threatens to increase the frequency, extent, and severity of fires through increased temperatures and drought,” the agency wrote. “Earlier spring melting and reduced snowpack result in decreased water availability during hot summer conditions, which in turn contributes to an increased wildfire risk, allowing fires to start more easily and burn hotter.”

However, it is unclear whether that means Air Force crews like those of the 302nd Wing will find themselves fighting more fires. Many factors affect whether Air Force MAFFS crews are sent in to help, and it’s not just the amount of acreage burning, Pantusa explained. For example, the most intense year for Air Force MAFFS in terms of sorties flown was 1994, and no military crews flew MAFFS missions in some years as recently as 2019, he said.

“There are a lot of variables: the contract civilian fleet gets larger and smaller based on federal funding,” the airman said. “And it’s not just that fire is burning, it’s where it burns, so significant risk to population centers is another factor.”

No matter what happens this summer, MAFFS crews like Pantusa’s are trained to respond when needed. The missions can bring up a strange mix of emotions, because while it is rewarding to pull off a MAFFS drop, it is also heartbreaking to meet people who lost their homes.

“We sometimes end up eating breakfast with folks whose house burned down,” Pantusa said. “It’s a spectrum of emotions, both rewarding and tragic.”

Hopefully there are far fewer folks with burned homes thanks to the efforts of the Air Force MAFFS program and the larger fleet of civilian contractors who do the mission year-round.

“It’s a culmination of a lot of training and cooperation because we do work with so many partners in both government and industry,” Pantusa said. “There’s a level of trust and competency which combine to do something really useful.”