President Biden announced plans in April to cut climate-warming emissions in half by 2030. It’s a necessary undertaking to prevent us from hurtling toward disastrous and irreversible climate changes.

But ramping up clean energy isn’t without its own thorny considerations. One question is where to put all those renewables. If sun and wind provide 98 percent of energy by 2050, that could quadruple the amount of land required to produce energy, according to an analysis by Bloomberg and Princeton University.

That’s why policymakers are looking to the sea for solutions. The President also recently pledged to develop 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030—a goal that, if achieved, could alleviate the pressure on land to support vast acres of energy development.

Today, there’s only a couple small offshore wind plants in the States. But the Department of Energy reports that 28,581 megawatts of offshore capacity are currently on their way to fruition. Here’s how those projects could help us meet America’s clean energy goals.

How offshore wind works

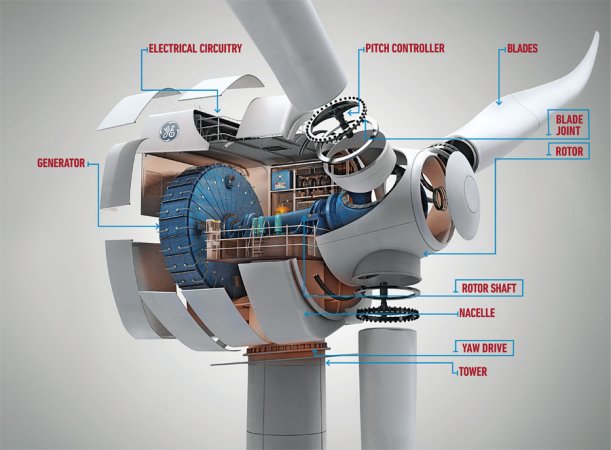

Offshore wind turbines route power to shore using buried wires. The turbines above water don’t look all that different from windmills on land—except for their size. Offshore turbines are about twice as big as those on land, extending more than 500 feet from the water to the tip of their blades.

Not only are they ideal in that they avoid using land, but offshore wind plants can also produce more power because ocean gusts tend to blow stronger and more consistently. That’s simply because there are few obstacles for wind at sea—no mountains, valleys, or buildings.

Offshore turbines are usually mounted on a fixed foundation that’s pounded into the seabed, which limits construction to water shallower than about 200 feet. But newer floating technology, which buoys the turbines while keeping them in place with a mooring line, could allow developers to install turbines in deeper seas. It’s an enticing possibility—more than half of potential US offshore wind resources are in waters deeper than 200 feet.

Offshore turbines can supply a lot of power

Researchers at the National Renewable Energy Lab have estimated that offshore wind resources have the potential to supply nearly double the amount of energy Americans currently use. “We’re never going to do that, but that gives you an idea of how much resource we have,” says Walter Musial, the offshore wind research lead at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Open coastal waters are necessary for other uses, like fishing, and many inland states are better served by land-based energy generation. “You wouldn’t necessarily use offshore wind resources to power Kansas City.”

Still, with about 80 percent of the country’s population living along its coasts, tapping into the sea’s stores of wind energy could prove invaluable, especially where there’s little room to develop energy on land such as in the Northeast.

As for meeting 30 gigawatts by 3030? Musial says it’s definitely doable, but not without its barriers.

The hurdles to offshore wind

To usher in turbines, the federal government has to lease ocean space to wind developers, a process of citing and permitting that can grind on for years. It also requires negotiating with other groups who need access to those waters, including the military, shipping, and fishing industries. Fishers have raised concerns about how the developments could preclude them from their fishing grounds. “Our fisheries are already more strictly regulated than anywhere else in the world, so it’s not just as simple as saying fishermen can just change their gear and go fish somewhere else,” Annie Hawkins, the executive director of the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, told the New York Times recently.

Another issue is building transmission infrastructure on land. Though at first offshore wind farms could essentially plug into the grid wherever fossil power previously did, there will eventually be a need for new transmission lines. To get off fossil fuels, not only will cars need to tap into the grid to charge, but many appliances will also need to be electrified; that means our future energy needs are going to be much greater and thus demand more transmission infrastructure. These lines can be challenging to plan out and build because it requires approvals from many levels of government and landowners. “It’s more complicated than the wind farm,” says Musial.

There’s also some unknowns about how the facilities will affect ocean life. When fixed turbines are mounted into the seafloor, the installation process can produce a racket underwater. A clanging 10-foot diameter pipe being hammered into the seafloor could stress out marine animals like endangered right whales. Luckily, there are techniques to lessen the sound available, such as creating a ball of bubbles around the construction area that breaks up the sound.

Why offshore wind is a cost effective and reliable resource

Offshore wind, though not without its challenges, could provide a large wedge of the country’s future power needs. And much like solar power, wind power costs (including offshore wind) have dropped since the first turbines cropped up. Though there are few offshore turbines in the US currently, offshore wind farm development in Europe and Asia has led to costs plummeting. “Offshore wind is far more cost competitive today than it was just five years ago,” says Ryan Wiser, a senior scientist focused on electricity markets and policy development at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “And indeed, that’s one of the key reasons a growing number of states, especially in the East Coast, but perhaps as well in the near future on the West Coast, have established more aggressive offshore wind targets.”

Wiser and other researchers with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have estimated that wind prices (including offshore) could go down to half what they were in 2015 by 2050. “There are definitely a number of recent studies that have shown that even with very deep decarbonisation in the power sector, we may well be talking about costs and prices that are not that dissimilar from what we observe today, as households,” says Wiser. “And the simple reason for that is that the cost of several key low-carbon technologies have declined on an accelerated basis.”

The myth that Musial confronts most often is that reliance on solar and wind will lead to less reliable power. But grid operators already deal with fluctuating power demand throughout the day and across seasons. With the right mix of clean sources, our supply will be sufficient, he says.

“The bottom line about offshore wind or any renewable energy system is that the reliability and the flexibility of the grid to deliver power is not going to change,” says Musial. While we will need to implement new technologies to store power, the fluctuations of the sun and wind are not insurmountable obstacles. “It’s a myth that the reliability of the grid is going to go down.”