The atmosphere that blankets our planet contains around 5,600 trillion tons of air. It can blast the ground below with lightning, torrential rain, heat waves, and tornadoes, or caress it with a light breeze or dusting of snowflakes. As the past few days have reminded us, it’s no small feat to make predictions about what this vast, seething mass of wind and water will do.

But our forecasting prowess—at least when it comes to predicting how hot the coming days will be—has been making impressive strides. High-temperature predictions have improved significantly over the past 12 years, according to a new report from ForecastWatch, a Columbus, Ohio-based company that assesses the accuracy of weather forecasts. In fact, our ability to pin down the next day’s high temperature has improved by almost a degree Fahrenheit, says founder Eric Floehr.

That might not sound like much of an upgrade. But there’s a lot riding on weather forecasts, and a relatively small boost in accuracy can make a big difference when a country is faced with a natural disaster. And as weather forecasts become ever more sophisticated, you may come to realize that they’ve infiltrated other realms of technology to innocuously improve more typical days as well.

“We’re in the middle of this big revolution in how we use weather,” says Bill Gail, co-founder and CTO of Global Weather Corporation, based in Boulder, Colorado, which provides forecasts to utilities and other businesses. “In a decade…those of us who already use weather information will be using it 100 times as often and won’t even know it.”

Weather, weather everywhere

There are some obvious benefits to having reliable weather reports, like advance warning before hurricanes like the recent Harvey. Predicting the path of a hurricane is essential to keeping people out of harm’s way. Still, fleeing a storm can be expensive. It’s been estimated that it costs $1 million per mile of coastline to evacuate before a hurricane. And as was the case in Houston last week, it can be difficult to determine whether or not forced evacuations will do more harm than good. Having more precise forecasts in future could cut down on the number of people who have to seek shelter, and help those in the path of the worst of the weather make crucial decisions.

But outside of catastrophic events, less crucial forecasting needs still add up. Each year, companies in the United States lose more than $500 billion because of weather-related problems. Floehr says he consults with businesses that use weather forecasts in their decision-making as well as groups that provide weather forecasts to the public.

Sometimes, they work with sports teams that need to predict how many people might come to a game. That means factoring the weather into their calculations, which is not a straightforward affair. If a team is counting on fans buying tickets for a game scheduled for Friday, they must consider the forecast from several days earlier. Sometimes, “That person looks at the forecast on Wednesday and says, ‘you know what, I’m not going to the hassle of trying to take off Friday afternoon for the game if there’s a 50 percent chance of rain,'” Floehr says. “And it doesn’t matter if it rained or not on Friday, that consumer made his decision on Wednesday.”

And power companies need accurate weather forecasts to predict how much energy people in their service area will draw on. “It costs a lot of money and it takes time to turn on a generator, so you don’t want to turn it on if you are going to waste the energy,” Floehr says. “In the energy industry, even a sway of a half a degree on average in accuracy really translates into bottom line savings.”

Providers also must estimate how much power they will be able to generate from wind or solar farms. If a day is less breezy than anticipated, they may have to buy electricity on the energy spot market to make up the difference, Gail says. His company, Global Weather Corporation, now provides wind forecasts to Xcel Energy. Xcel serves eight western and Midwestern states and gets nearly 20 percent of its power from wind energy. In 2015, Xcel estimated that improvements in forecasting had saved its customers $49 million.

Increasingly, forecasters are answering questions that go beyond the weather itself. When a storm hits, power lines can be knocked down. But some are more vulnerable than others, such as power lines that run through trees. Utilities must decide whether they will need to call in trucks from other cities and send them to areas that are most likely to be damaged in a squall. In the past, Gail says, forecasters would simply inform them that a particular area is liable to feel high winds or other stormy conditions. “What they’re telling us is, don’t tell us about icing or wind or anything like that—tell us where we should park our people…a day ahead so that they can respond quickly if power lines go down,” Gail says.

Feeling the heat

A forecast starts with measurements of elements like temperature, wind, or humidity. These observations, gathered by balloons, satellites, ground-based weather stations and other equipment, are fed into computer algorithms, many run by government agencies like the National Weather Service. “A computer model is basically a replica of the entire atmosphere—how it moves, and the energy that goes into it,” Gail says. These simulations can fill in space where observations are sparse and then predict what will happen in future.

Forecasters collect these weather models and look for trends that emerge. “Everyone pulls these models together, but they may pull them together in different ways,” Floehr says. Commercial forecasters can tailor their outputs to answer particular questions the businesses they work with are interested in. Different providers do better with certain types of forecasts. “There’s no such thing as one most accurate provider on all measures,” Floehr says.

He and his colleagues determine accuracy by looking at the difference between actual and predicted temperatures over time, and have built up a dozen years worth of forecasts. For the new report, they gathered weather forecasts every day for more than 750 locations around the United States, and information about how hot it actually was taken at weather stations located in airports and landmarks like Central Park. From 2005 to 2016, they tracked predictions from 10 forecasters, including The Weather Channel, AccuWeather, and the National Weather Service.

How accurately we predict temperature varies by season, slacking off a bit in winter. But over the past 12 years, Floehr and his team saw, forecasts for daily high temperatures have become more accurate across the board. Forecasts can correctly estimate tomorrow’s peak warmth to within 3 degrees of the actual highest temperature about 80 percent of the time. Before, the margin of error was closer to 4 degrees.

Five-day outlooks have made even more progress, improving nearly a degree and a half on average. About 57 percent of five-day forecasts fall within 3 degrees of the actual temperature, up from a not-so-impressive 44 percent.

Today, we can guess the high temperature three days into the future as well as we could predict tomorrow’s weather 12 years ago, Floehr says. And our five-day forecasts are, on average, as skilled as 2005’s three-day predictions.

He is planning to do similar reports for low temperature (perhaps within the next year) and precipitation. He’s also noticing signs that the commercial providers are improving at a faster clip than the National Weather Service, perhaps because they have more freedom to innovate, and plans to investigate this in a future report as well.

A long way to go

We have a few things to thank for our increasingly powerful weather forecasts.

Our equipment is getting better all the time—NASA’s GOES-16 satellite, which launched in November, can scan the Earth five times faster and with better image resolution than previous satellites.

We can come up with models that operate at increasingly fine scales. We can hone in on terrain just a few miles wide, instead of patches spanning tens of miles, Gail says.

And we’re getting better at understanding how the atmosphere works, and how thunderstorms or other disturbances evolve.

Still, we have a long way to go. “You’re dealing with something ultimately that is inherently unpredictable,” says Greg Carbin, Forecast Operations Branch Chief for the National Weather Service Weather Prediction Center in College Park, Maryland. “At some range in the future it doesn’t matter how good your computer models are, the way the atmosphere is chaotic in nature, your predictability will break down.” For most forecasts, he says, this happens at around seven to 10 days.

There are some elements of the atmosphere we still struggle to predict. The intricate details that make one tornado fearsome and another short-lived are poorly understood. Other events, like thunderstorms, are commonplace but unfold over tiny areas. Our ability to guess how intense a hurricane will become is also still in its infancy. Forecasters had a remarkably good idea of how devastating Hurricane Harvey might be as it began to approach land, but were reluctant to believe the worst possible scenario with the the evidence available to them—and the storm still brought a few terrible surprises. “You’re not able to follow every molecule of air in the entire atmosphere,” Gail says.

The United States, gifted as it is with varied geography and some pretty dramatic weather, can be a handful for forecasters. “Weather is a little more dynamic in the U.S. than it is in Europe,” Gail admits. And we still have a lot of gaps the models must fill in from places where there are fewer weather stations.

These holes in our data matter for more than the people who live in areas that are sparsely furnished with forecasting equipment. As you move further out in your predictions, you have to know not just what’s happening where you live but what perturbations are unfolding all over the world. “Weather today comes from someplace else in the world a few days in the past,” Gail says. “You have to know what’s bubbling up in Siberia to know what’s going to happen here in the US in a few days or a week.”

On top of all this, the conviction with which forecasters describe an event can actually break down as it looms closer. The smaller the scale you’re forecasting on, the more difficult the prediction is usually, Carbin says. “People think you should be more confident as you get closer to the event, but it doesn’t always work that way,” he says. “Maybe [at the end of June] I was very confident that thunderstorms were probably going to interrupt July 4th fireworks. But on the day of the event, depending on where your fireworks are, the thunderstorm could [wind up] 10 miles away and not interrupt the event at all.”

Behind the scenes

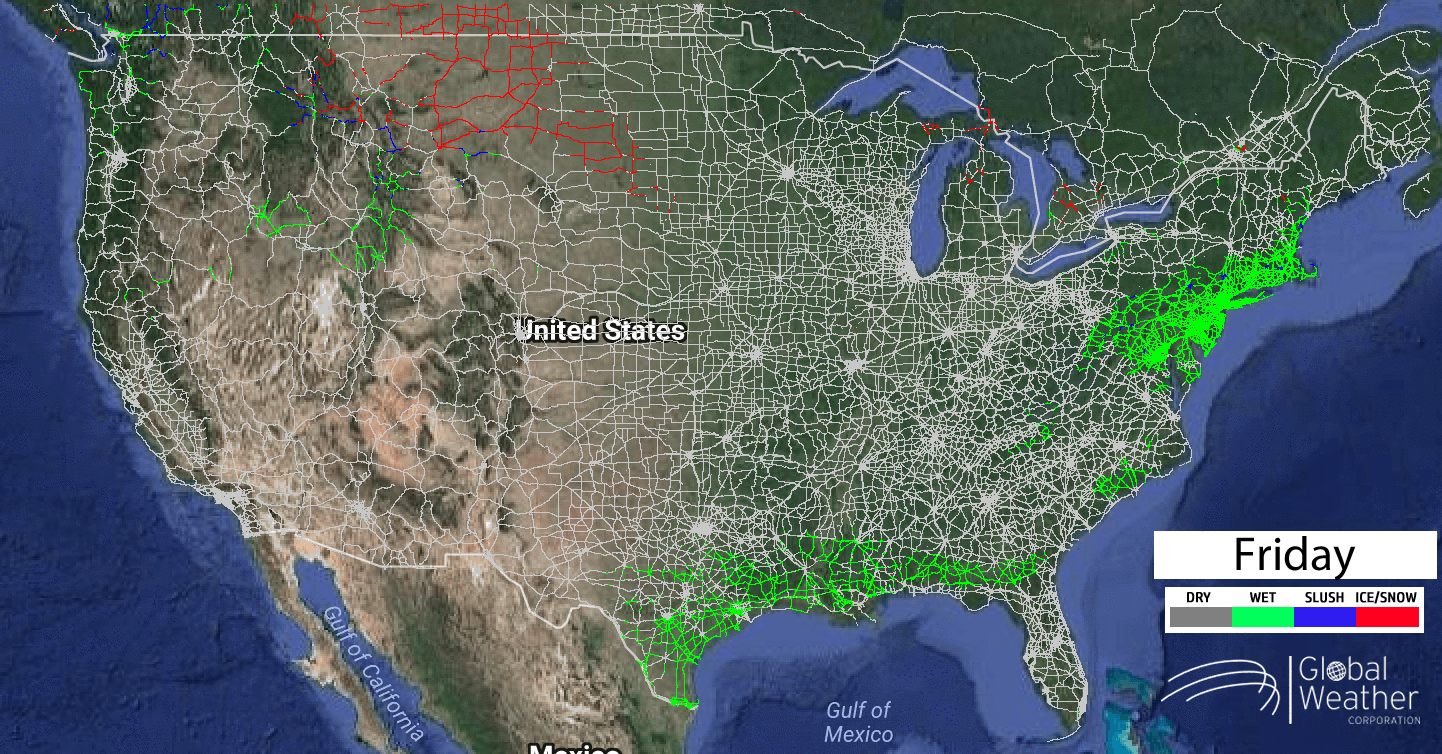

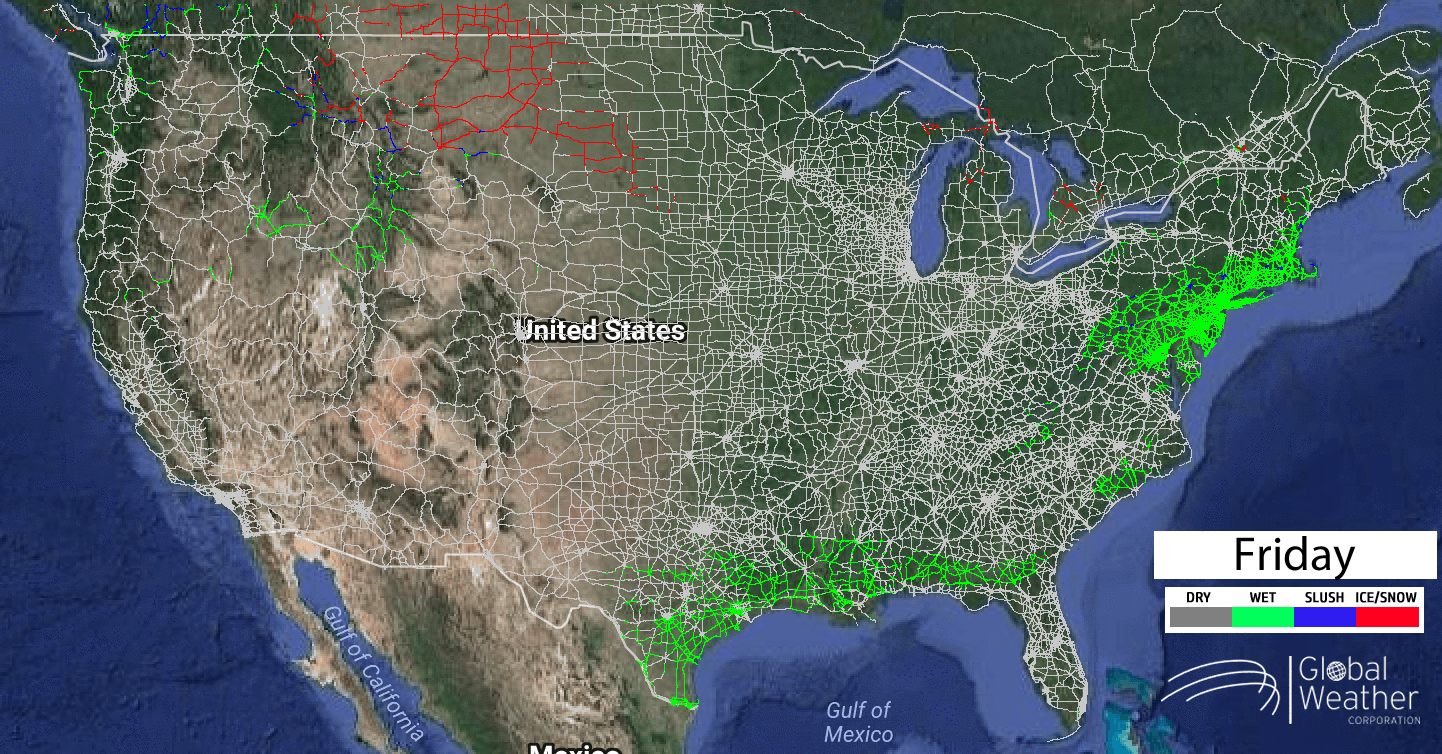

Still, our forecasts are getting better, and there are a few ways that these improvements could save lives. About 22 percent of all vehicle crashes are weather-related; around 5,900 people die every year in these accidents. “This is the equivalent of one airliner going down every week and nobody really caring very much about it,” Gail says. “Good, accurate information that tells you where the roads are going to be slippery would have an enormous impact.”

Global Weather Corporation is coming up with forecasts for how slick or icy the roads are in the United States, Europe, and China. This intel will be fed to connected cars, so drivers will receive alerts if dangerous conditions are on the horizon.

“It didn’t do much good to have weather forecasts for road surface conditions before, since none of the drivers could actually get that information,” Gail says. Now, car companies offer in-vehicle communication systems that can display weather information. Still, “Weather information is sort of buried in the menu selections,” Gail says. “It should be something that comes up all the time when you’re driving.”

Soon, your map will automatically include forecasts when it advises you to take a particular route. And before long, Gail says, we will be slipping weather predictions into decisions made behind the scenes, so you will benefit from forecasts without having to consciously think about the weather.

“The future is, you get weather information on your phone tied to your schedule, tied to where you’re driving, tied to all the different things you’re doing during the day,” Gail says. “The old paradigm was, you look at your map and…you get the weather and you try to combine those two in your head. Why should you be doing that? Why shouldn’t your app being doing that for you?”