When Winter Storm Grayson plowed into the East Coast earlier this month, it brought a few unwelcome gifts—namely brutal cold, power outages, coastal flooding, and whiteout conditions from Virginia to Maine. But the blizzard also gave parts of New York and New England the chance to experience the rare and thrilling weather event known as thundersnow. It happens when a snowstorm produces thunder and lightning, and has been known to send meteorologists into ecstasies of delight.

It might seem odd to have lightning flashing in the middle of a blizzard. In fact, thundersnow isn’t really that mysterious. “Lightning and thunder, they don’t care about the calendar, whether it’s January or any other month,” says Antti Mäkelä, a climate scientist at the Finnish Meteorological Institute in Helsinki. “If conditions in the atmosphere are favorable then lightning can occur and it’s the same type of lightning that occurs in the summertime.”

Thundersnow does have its dark side, though. Winter thunderstorms can be particularly dangerous exactly because they are so unexpected. Fortunately, we’re getting better at forecasting and understanding thundersnow.

Hang on. If it’s the same as regular lightning, why don’t we have thundersnow all the time in winter?

Thundersnow storms tend to be a little smaller and weaker than the storms that produce lightning in spring and summer. However, both types of storms need moisture and air currents traveling upwards to produce lightning. “You need instability in the atmosphere; that’s kind of the fuel that drives thunderstorms, and drives those upward motions,” says Matthew Kumjian, an atmospheric scientist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park.

Inside the cloud, rising particles collide with those falling down and become charged. The negatively charged particles gather at the bottom of the cloud, and the smaller, positively charged ones wind up toward the top. Eventually, the cloud will build up enough electricity that some is discharged as lightning.

In winter, these elements come together less frequently than during the warm season, Kumjian says. “A lot of the normal, day-to-day snow bands that people might experience in the northern part of the country, those often do not have the right ingredients to get the type of instability that you need to get the thundersnow.” However, it can sometimes be created in lake-effect snow as cold air moves over relatively warmer water, or when air is forced to rise in strong nor’easters.

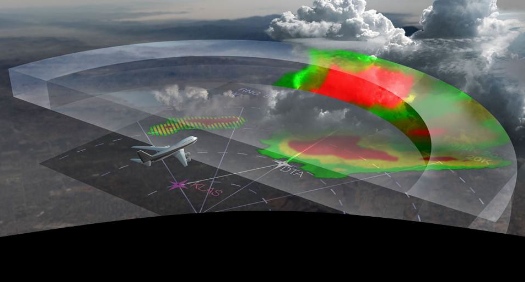

Thundersnow storms typically only manage to produce a handful of lightning strikes, while summer thunderstorms can produce thousands of zaps per storm, Mäkelä says. Often, thundersnow storms won’t even be able to form lightning until an airplane triggers it by flying too close to a heavily charged cloud.

The areas that experience lightning during a snowstorm also tend to be those that receive the heaviest snowfall. As with summer thunderstorms, “Most of the electrification occurs in that same area where the heavy precipitation starts to come down,” Mäkelä says.

How rare is thundersnow anyway?

Short answer: we don’t know.

Some areas do get more thundersnow than others, including those near large bodies of water and parts of the mountainous western United States. Japan and Finland seem especially prone to thundersnow because they have so much coastline, Mäkelä says. Another hotspot is the Palmer Divide, a large ridge in central Colorado that lies between Denver and Colorado Springs. When winds slam into this formation they can be forced upwards, creating the lift needed to kick start the processes that eventually lead to lightning.

Over the past few decades, scientists have tried to figure out how often thundersnow strikes. “These types of events…ended up looking like they were extremely rare, maybe only happening a few times across the entire United States per year,” Kumjian says. “But in recent decades we’ve been developing better tools to detect lightning flashes.”

A few years ago, he received funding from the National Science Foundation to investigate thundersnow in Colorado. That year, Kumjian and his colleagues reported 17 different thundersnow storms in the northern part of the state alone. “The previous climatology said that part of the country should only have less than one per year, so I think it’s probably safe to say that it’s more common than once thought,” Kumjian says. However, “The jury is still out on exactly how often this happens.”

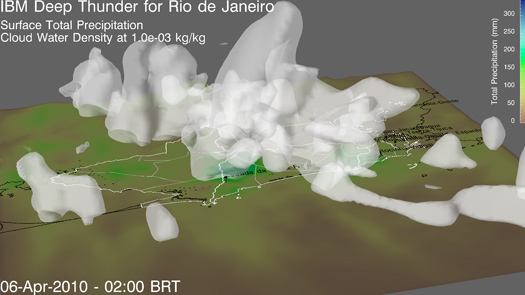

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s GOES-16 satellite has been collecting information on lightning flashes across the United States, and might be able to give us a more detailed picture of thundersnow, he says.

Is it dangerous?

Thundersnow is a problem for airplanes. In Finland, planes are actually more likely to be struck by lightning in the winter months because pilots know to avoid thunderclouds when it’s warm out, but may not take the same precautions in colder weather, Mäkelä says. On one day in October 2011, ten different planes trying to depart from or land at Helsinki Airport were struck by lightning. When Mäkelä interviewed the pilots, some reported being temporarily blinded or deafened. The temperature on this day was a little above freezing, so the storm they were traveling through wasn’t quite thundersnow, but it did demonstrate how much rarer cold-weather thunderstorms are—and how little pilots expect them to produce lightning.

Fortunately, airplanes are built to withstand lightning strikes. But the combination of thundersnow and airplanes can still be dangerous for people on the ground. A couple winters ago, a plane that was trying to land at Helsinki Airport triggered a lightning strike that passed to the ground and hit a house, which then burned down, Mäkelä says.

And for people outside, there’s probably even less warning that thundersnow is about to strike than you’d get with a warm season storm. “People are generally not expecting it to lightning when it’s snowing outside so there’s always that element of being caught off-guard that makes people a little more vulnerable,” Kumjian says.

Plus, the fact that thundersnow doesn’t produce a lot of flashes means you’re even more likely to be caught by surprise. And even if there was a previous strike, you might not know about it. “The snow itself can kind of muffle the sound of the thunder, so you don’t hear the thunder as far away from where the flash actually occurs as you would normally in a warmer season thunderstorm,” Kumjian says.

That said, the chances of getting struck by lightning during a thundersnow storm are much lower than in summer storms, which produce many more lightning bolts.

So can we predict thundersnow?

Forecasters are getting pretty good at identifying which areas will have a high risk of lightning during an event like Winter Storm Grayson, Kumjian says. “And indeed, the big cyclone was actually pretty electrically active.”

And once a huge winter storm is underway, we might even be able to predict imminent lightning strikes. Forecasters have identified a distinct radar signature associated with strengthening electric charge. It happens when ice crystals in the cloud get caught by the electrical field. This makes the crystals tilt instead of drifting with their longest sides facing downwards like a sheet of paper you’ve just dropped. “When you get these kind of tilted ice crystals in the cloud, that does something to the radar signal that shows up pretty clearly,” Kumjian says. In nor’easters, he’s seen that this indicates a strong electric field is forming and a lightning flash may happen in the next five to 20 minutes.

This radar signal can only be caused by ice; raindrops are too heavy and fall too quickly to be much affected by the cloud’s electric field. “So it’s either higher up in a normal season thunderstorm or anywhere in a thundersnow storm,” Kumjian says.

The signature wouldn’t really be that useful for summer storms; there’s not much doubt that a developing thunderstorm will produce lots of lightning. But thundersnow is another story. “The radar signal might be an intriguing way to start to give you that short-term heads up that something is happening,” Kumjian says. “When you see it, at the very least I think the forecasters can say there is a much higher risk of a flash occurring sometime in the next 20 minutes.”

He plans to keep investigating how often thundersnow really happens and where it occurs most frequently around the country. Studying these storms could reveal how much buildup of electric charge is needed for a cloud to produce lightning on its own. “We could definitely learn something about the fundamental processes associated with lightning,” Kumjian says.

He himself has only experienced the joy of thundersnow on one occasion. It happened during his time as a graduate student in Oklahoma when he stepped outside during a blizzard. “Within a couple of seconds of me standing outside, I heard a fairly loud boom and quickly jumped back inside because it took me quite by surprise,” he says.

Still, he said, it’s always exciting to hear—if not see—this rare phenomenon in action. “It’s basically just like a thunderstorm in the warm season, just it happens to be snowing outside,” Kumjian says. “But it still doesn’t take away from the magic of it.”

![Spying On Thunderstorms From Space [Video]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/7IDHUIMONOAKW45PJUPLFYTXXI.jpg?w=525)