In recent years, scientists have been finding new ways to treat cancer outside of the chemotherapy and surgery combination. One technique, called immunotherapy, has showed promising results by reprogramming the patient’s immune system to attack tumors. Researchers from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle tested a version of immunotherapy on patients who had late-stage leukemia and lymphoma that had exhausted other treatment options—some weren’t expected to survive the experiment.

But the researchers were shocked to find that 27 of the 29 leukemia patients—that’s 94 percent of the study participants—went into complete remission and showed no more signs of the disease. Stanley Riddell, one of the researchers behind the trial, presented the unpublished results on Sunday at the annual AAAS meeting in Washington, D.C.

Our blood contains T cells, which are supposed to detect pathogens in the body. In this study, the researchers removed these cells from patient’s blood and tweaked their genes to recognize the cancer cells that would otherwise slip by the immune system.

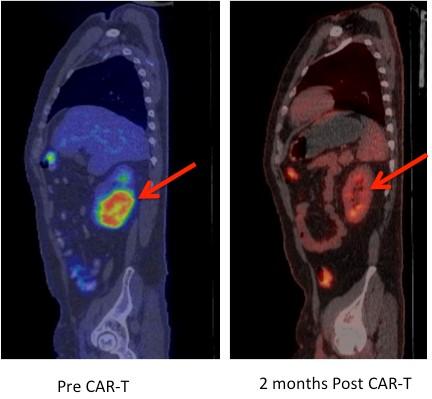

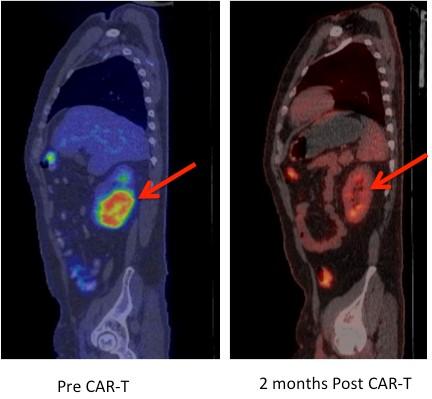

The resulting T cells, called CAR-T cells because of the special receptors inserted into them, are then put back in the body. Researchers hypothesized that the CAR-T cells would give the patient a long-term immune response—indeed, a few small but promising trials have corroborated it—but in many cases the T cells end up being less effective over time, either because the cells themselves become exhausted or because the cancer cells inhibit detection.

The results of this trial were different. In addition to the stunning results from the leukemia patients, 19 of 30 lymphoma patients responded to the treatment as well, after just a single dose of CAR-T cells. Many of the patients who were not expected to live for more than a few months are still alive now, three years after the trial started. “This is unprecedented in medicine, to be honest, to get response rates in this range in these very advanced patients,” Riddell said, according to the New York Post.

To the researchers, this strengthens the evidence that CAR-T cells (and immunotherapy in general) might be a viable treatment for cancers beyond lymphoma and leukemia.

But the treatment isn’t perfect quite yet. During the trial, seven patients developed cytokine release syndrome, a life-threatening inflammation that results when too many cancer cells are killed at once, and two of the patients died as a result.

While that might be acceptable risk for a last-ditch effort for patients with terminal cancer, such dramatic side effects wouldn’t be acceptable for patients with earlier stage or less lethal cancers, as Ars Technica reports.

The researchers don’t yet know the best dose for the treatment that wouldn’t cause such a strong reaction but would still get rid of the cancer, and they don’t know how long the patients will remain in remission. But they are heartened and encouraged by the results.

The researchers have submitted a draft of their study to a journal and hope that it will be published soon so that they can continue their work with immunotherapy, according to a press release.