From cities in the sky to robot butlers, futuristic visions fill the history of PopSci. In the Are we there yet? column we check in on progress towards our most ambitious promises. Read more from the series here.

While the quest for baseball’s inventor reads like a whodunnit, less murky is baseball’s sport-genealogy: It is descended from rounders (and to some extent cricket) and became a professional sport in the mid-19th century. Among the various rules that distinguish baseball from rounders is the role of the umpire. In baseball, the home-plate umpire calls every pitch in the game—ball or strike. In other sports, the umpire only makes calls as-needed—out-of-bounds, fouls, close plays—but the home-plate ump is mandated by the rules of the game to call every play. Because there are no lines painted around a strike zone, the home-plate ump’s play-calling is so conspicuous, and sometimes controversial, that efforts have been underway for more than a century to improve their accuracy through automation.

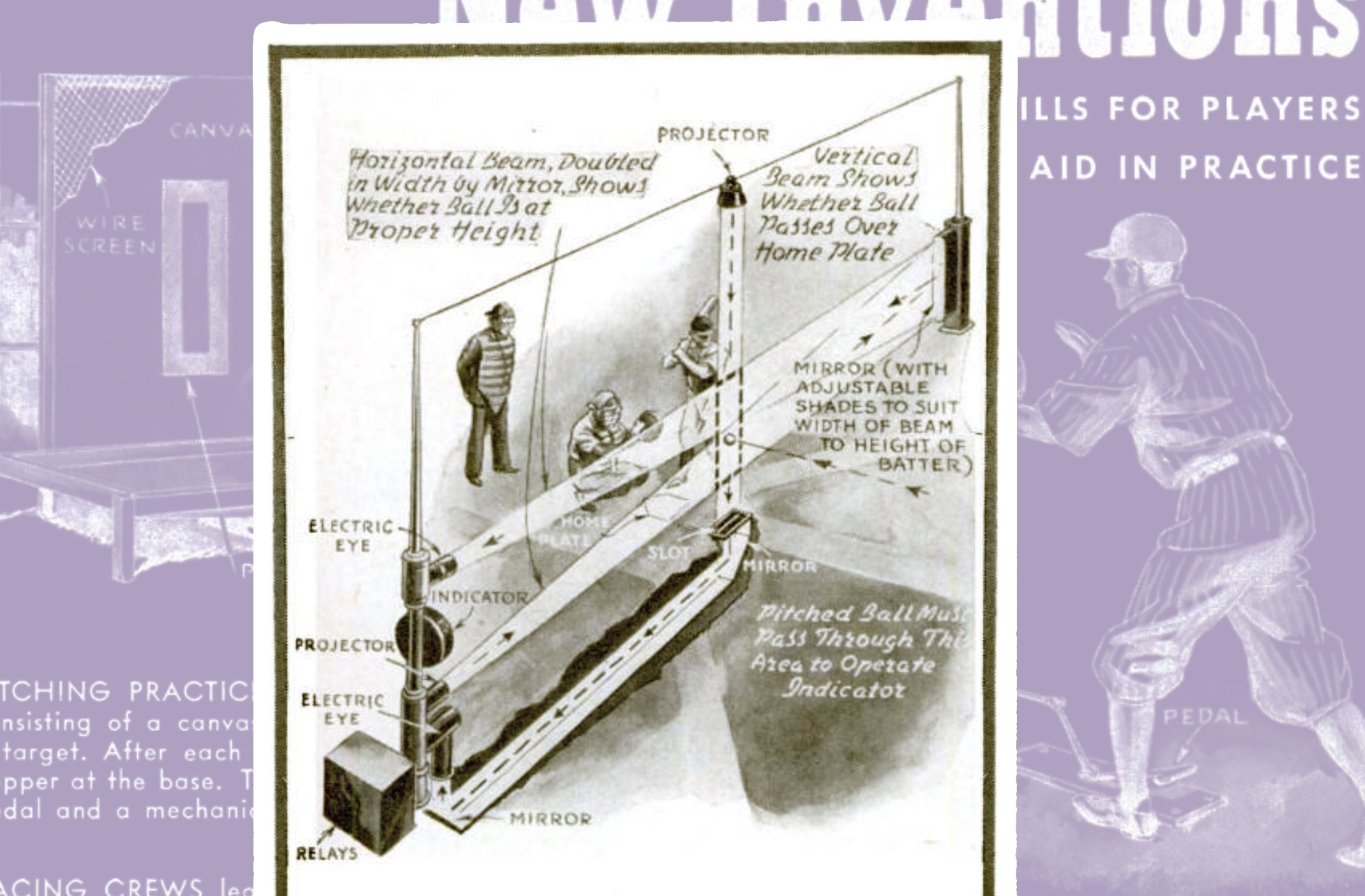

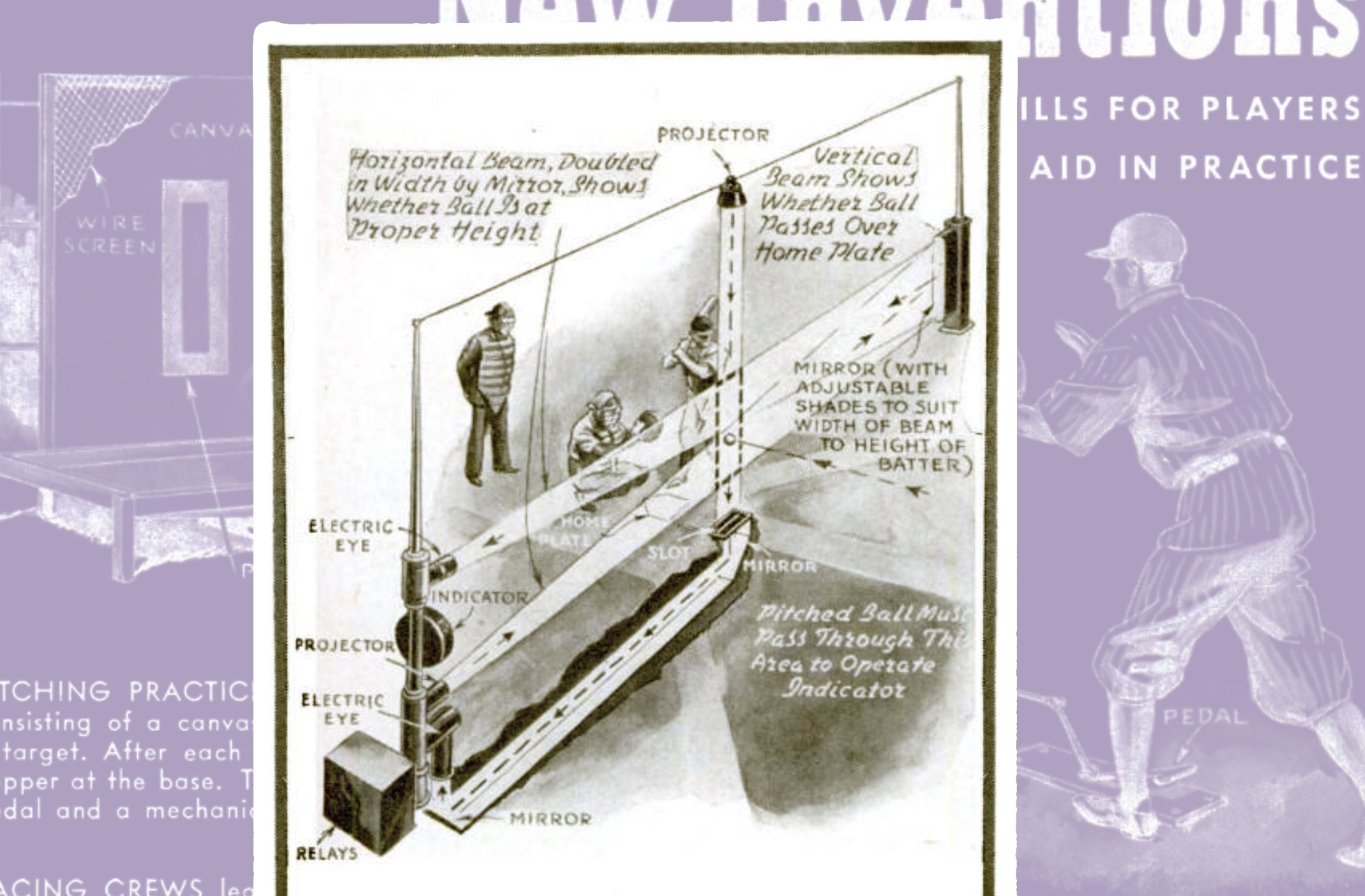

In a June 1939 roundup of new sports inventions, Popular Science included an “electrical umpire,” a device which used light beams to detect a ball passing through the strike zone and take “the guesswork out of calling ‘balls’ and ‘strikes.’” The 1939 version of a robotic home-plate umpire may have been among the first to use “electric eyes,” but it wasn’t the first machine to be used in a baseball diamond. A July 1916 Popular Science story also described a low-tech automated home-plate umpire designed to eliminate the guesswork in baseball training camps, little leagues, and carnivals. The 1916 device had a strike zone-sized opening cut into a sheet of canvas and was backstopped by a bowling-alley style ball-return register.

“The whole premise of officiating is the balance of art and science,” says Brenda Hilton, a senior director of officiating for the Big Ten Conference and founder of Officially Human, an organization dedicated to improving the treatment of sports officials, especially at the high school and lower level. “Do people really want to play or watch when there are robots [officiating]?” We’re not likely to see C-3PO dressed up in stripes anytime soon, if ever, but Hilton’s question applies equally to the less eye-grabbing automation that’s already here as well as what’s on the horizon.

Using technology to improve the performance of sports officials is not new. Instant replay has been around since 1963 when CBS TV director Tony Verna introduced it during the annual Army-Navy college football showdown that year. The NFL began experimenting with instant replay as early as 1976, but took another decade to fully implement it; the NHL followed in 1991; then the NBA in 2002. In 2008, Major League Baseball was the last of the four major American sports leagues to warm up to instant replay. But soon, it may become the first to flip the relationship between official and machine, allowing the technology to make the initial call.

In 2022, Major League Baseball debuted “robo-umps,” an automated ball-strike system (ABS), in their Triple A minor league, the last stop before the majors. In the new officiating arrangement, which is designed to be collaborative, the home-plate umpire still posts up behind the catcher, but is joined by a black box equipped with pitch-tracking radar. In addition to the standard protective gear, the human ump’s accessories include a smartphone and an earpiece to receive transmissions from the ABS. Instead of making the call, the ump merely announces what the system “sees,” giving voice to the ABS and intervening only when there’s an obvious error, like a pitch that hops across the plate. The goal of the ABS is to call pitches more accurately and provide a consistent strike zone, one that pitchers and hitters can rely on from one game to the next and one season to the next. Beyond its use in minor league trials and training camps, MLB has not announced any future rollouts.

[Related: Major League Baseball is nearing the era of the robot umpire]

But even if the decades-old vision of automated home-plate umpires may finally be here, it wouldn’t change the emotional investment of the players, coaches, and fans. After all, the umpire is more than just an arbiter of rules in a baseball game. “Who would the fans yell at?” Hilton asks. She’s only partly joking.

In all sports, umpires and referees hold a special place in the hearts and minds of players, coaches, and fans. Feelings toward these key people on the field and court are mostly negative, a trend that has been on the rise. According to a 2019 survey conducted by Officially Human, 59 percent of officials who officiate games at the high school level and below don’t feel respected and 60 percent ranked verbal abuse as the top reason they quit. A similar survey conducted by the National Association of Sports Officials in 2017, which included professional sports officials, reached similar conclusions: 48 percent of male officials have at times feared for their safety. The problem has become so acute at the high school level that the National Federation of High Schools estimates that “50,000 individuals have discontinued their service as high school officials,” according to their website, citing the unsportsmanlike behavior of players, coaches, parents, and fans as one of the primary reasons.

By adding technology, would it be possible to cool down heated emotions, reduce acrimony, or elevate respect for officials? Hilton thinks that with too much technology, “games may become unwatchable.” She admits her bias for human officials, but adds, “I think that fans would become more disengaged at the pro level if they went all electronic.” In a recent Wall Street Journal editorial, sports journalist James Hirsch seemed to agree, writing that instant replay “robs games of their drama.”

Every sport is, after all, part performing art—a production of humans on a stage, with all their emotions, inconsistencies, delights, disappointments, thrills, and surprises. Officials play integral parts in every performance, sometimes by assuming attention-grabbing roles—making critical calls that change outcomes—but mostly by playing mundane parts to keep the show on track: throwing the ball up, dropping the puck, calling out of bounds, and offering a steady presence when tempers flare on the field.

[Related: Radium was once cast as an elixir of youth. Are today’s ideas any better?]

Still, technology seems to have carved out a relatively permanent role in those performances. In a 2021 Morning Consult survey, 60 percent of sports fans believe that instant replay should be used “as much as possible to ensure the accuracy of calls” while another 30 percent believe it should be used on a limited basis “to maintain the flow of a game.” The remaining fans didn’t know or had no opinion. None said no to instant replay.

Sports fans are already seeing their wish for more technology come true. For instance, the April 2022 debut of the US Football League was dominated by drones to offer more camera angles for viewers and replays. In 2021, the NFL added Hawk-Eye’s Synchronized Multi-Angle Replay Technology, or SMART, to its arsenal of instant replay cameras. Hawk-Eye is best known for its role in tennis, but is also used as goal-line technology in international soccer.

Yet, with all that extra technology, what’s become clear is that human officials are pretty darn good at their jobs, especially at the professional level. According to CBS Sports, in the 2020 NFL season, there were 40,032 plays of which only 364 were reviewed, or less than 1 percent. Of the reviewed plays, about half were reversed, which was a little higher than previous seasons. Viewed from the officials’ lens, human referees were right 99.5 percent of the time.

Judging by the pace of instant-replay adoption, not to mention that “electric umpires” have been an option since at least 1939, it’s not likely that Major League Baseball will implement robo-umps in the majors anytime soon. But that won’t stop sports innovators from developing new systems or tech enthusiasts from advocating for automation. “There’s a great balance somewhere,” Hilton says. “We just have to figure out what that balance is.”