About 5.7 million Americans suffer from heart failure, meaning their hearts don’t pump blood as well as they should. The affliction costs the nation about $32 billion a year, and there’s no cure. But a squishy, air-powered robot might be able to help.

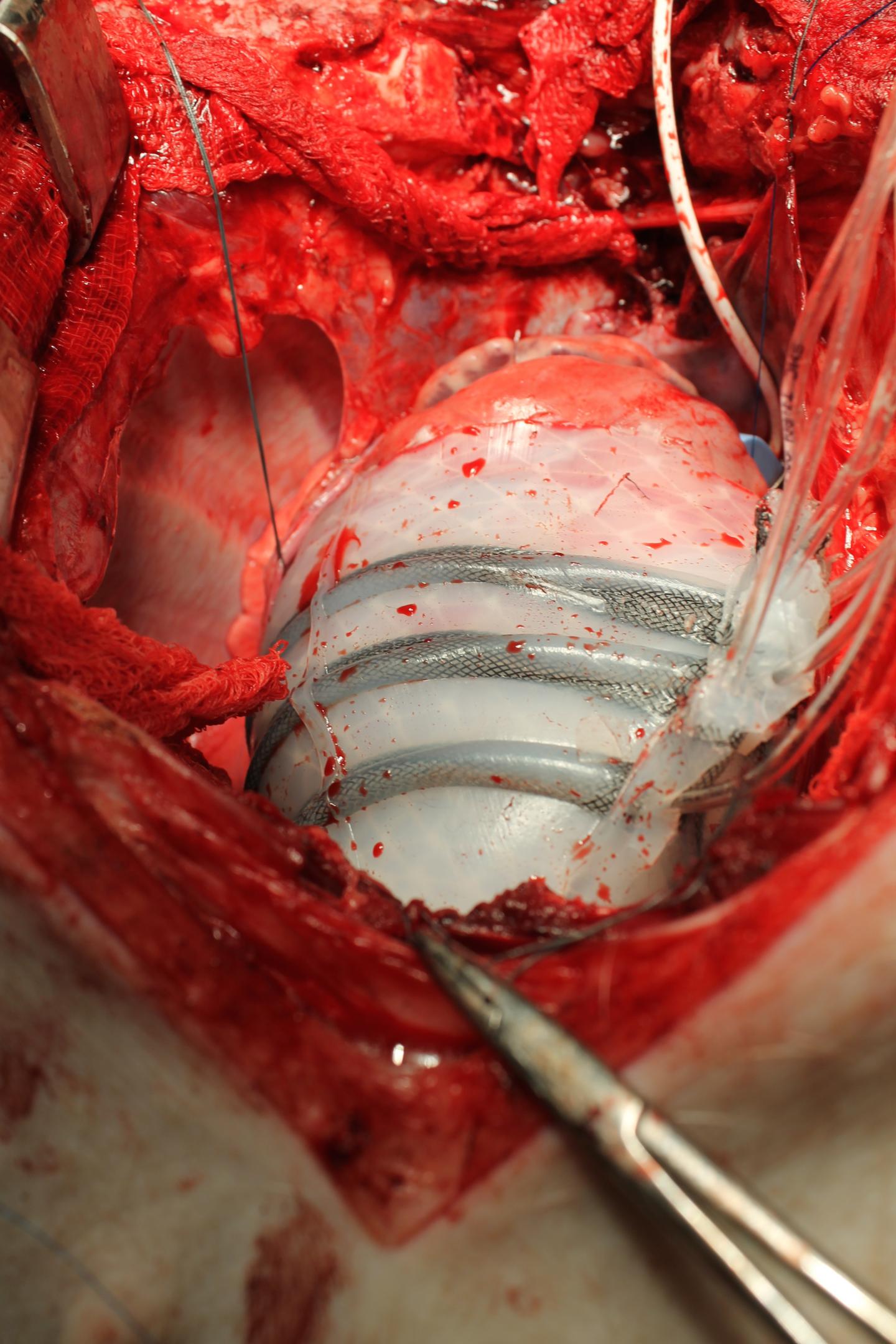

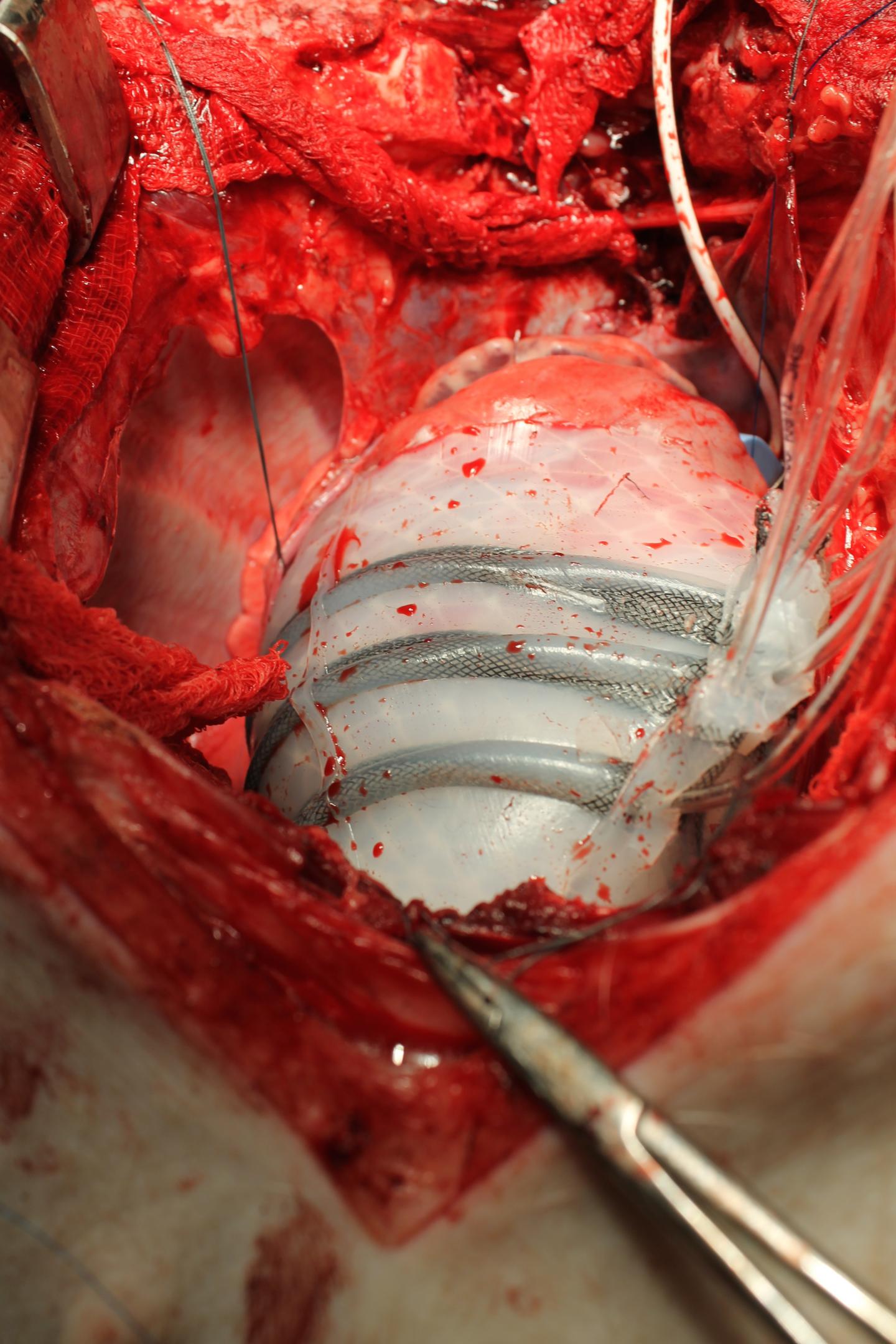

A team lead by engineers at Harvard University is testing a silicone sleeve that slips over the bottom of the heart like a cocoon, then inflates and deflates to squeeze the heart and give it a powerful beat. Proof-of-concept studies showed that the soft robot restored normal blood flow in six pigs whose hearts had stopped.

There’s still a lot more work to be done, including long-term studies in animals (and then humans). But if the experiments continue to be successful, the robot may one day provide an alternative to the current treatment for severe heart failure. Doctors implant ventricular assist devices (VADs) to keep a patient’s heart pumping while waiting for a transplant, or to keep them alive indefinitely.

VADs pipe blood from the heart through a mechanical pump and then into the arteries. The machines save lives, but because they come in direct contact with blood, the patient has to be on blood thinners to avoid clots that gum up the works.

The soft robotic pump doesn’t come into contact with blood. The thin sleeve slips over the outside of the heart, twisting and contracting to mimic the muscle’s natural movements.

To test it, the researchers induced cardiac arrest in six pigs, then used the sleeve to get their hearts pumping blood again for 15 minutes or more.

That’s promising news, but several challenges lie ahead. After getting squeezed and released by the device for two hours, pig and rodent heart tissue became inflamed, especially in the region where a suction cup secured the device to the heart. Attempts to fix the problem by coating the heart with a hydrogel before attaching the device didn’t quite work, so the researchers will have to develop some other kind of adhesive.

The system is also fairly bulky. The heart sleeve is tethered to an external air compressor that continually inflates and deflates it. The authors hope to make the system more portable, so that the air compressor and power supply could be worn on a belt around the waist, but it’s likely the next version will still have cables sticking out of the patient’s torso to connect the sleeve to the power supply. That’s similar to today’s VADs. But eventually the technology might become fully implantable.

Maybe one day the device will help treat other types of cardiac diseases, says study co-author Ellen Roche, as well as fix ailments in other organs. Who knew hugs could pack so much healing power?