Last November, at Fort Campbell, Tennessee, half a mile from the Kentucky border, a single human directed a swarm of 130 robots. The swarm, including uncrewed planes, quadcopters, and ground vehicles, scouted the mock buildings of the Cassidy Range Complex, creating and sharing information visible not just to the human operator but to other people on the same network. The exercise was part of DARPA’s OFFensive Swarm-Enabled Tactics (OFFSET) program.

If the experiment can be replicated outside the controlled settings of a test environment, it suggests that managing swarms in war could be as easy as point and click for operators in the field.

“The operator of our swarm really was interacting with things as a collective, not as individuals,” says Shane Clark, of Raytheon BBN, who was the company’s main lead for OFFSET. “We had done the work to establish the sort of baseline levels of autonomy to really support those many-to-one interactions in a natural way.”

Piloting even one drone can be so taxing that it’s not rare to see videos of first-time flights leading immediately to crashes. Getting to the point where a single human can control more than a hundred drones takes some skill—and a lot of artificial intelligence.

In total, the swarm operator directed 130 vehicles in the physical world, as well as 30 simulated drones operating in the virtual environment. These 30 virtual drones were integrated into the swarm’s planning and appeared as indistinguishable from the others in the program to the human operator, and to the rest of the swarm. As apparitions of pure code, tracked by the swarm AI, these virtual drones flew in formation with the physical drones, and maneuvered around as though they really existed in physical space.

How a human commanded the swarm

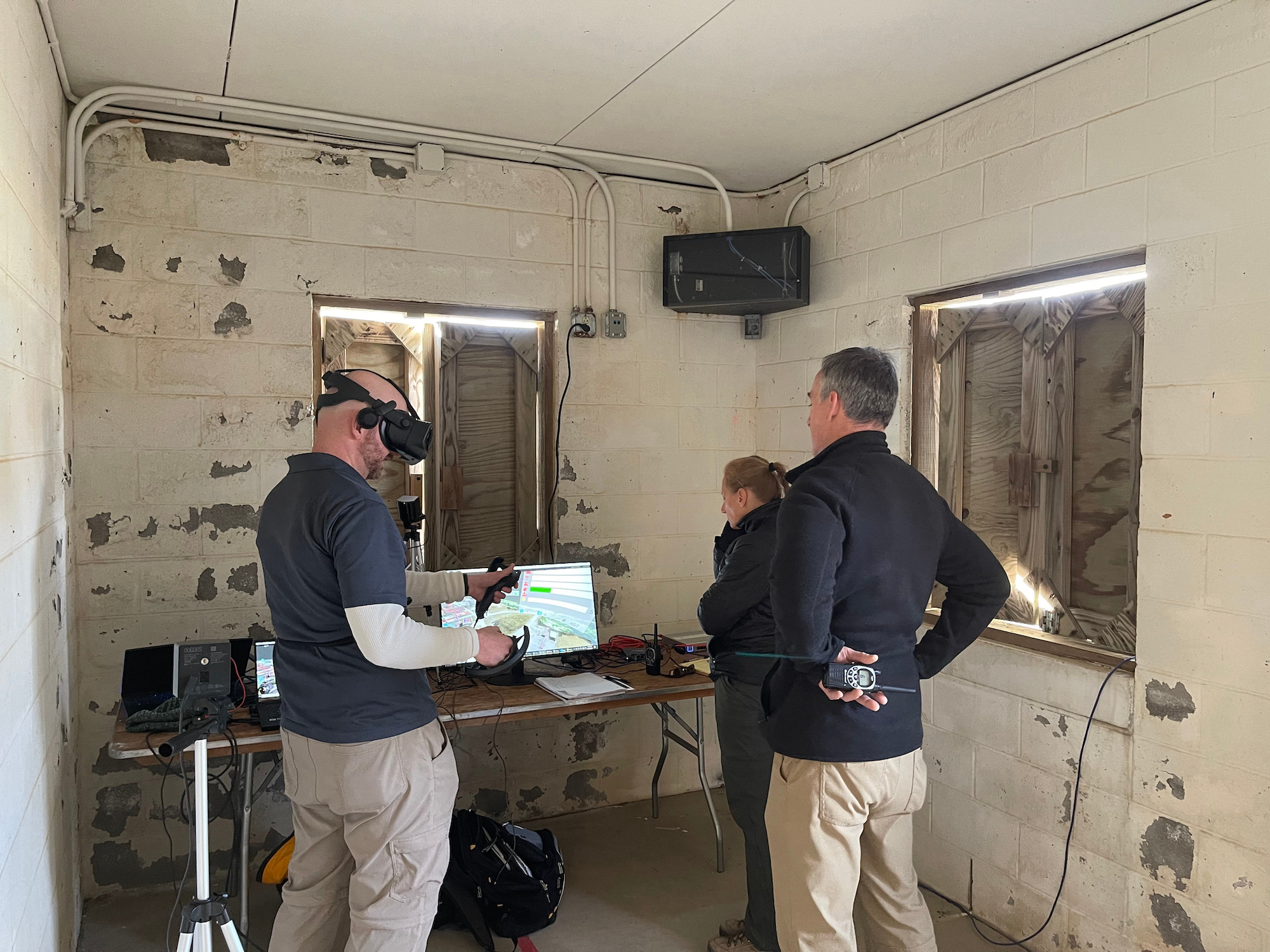

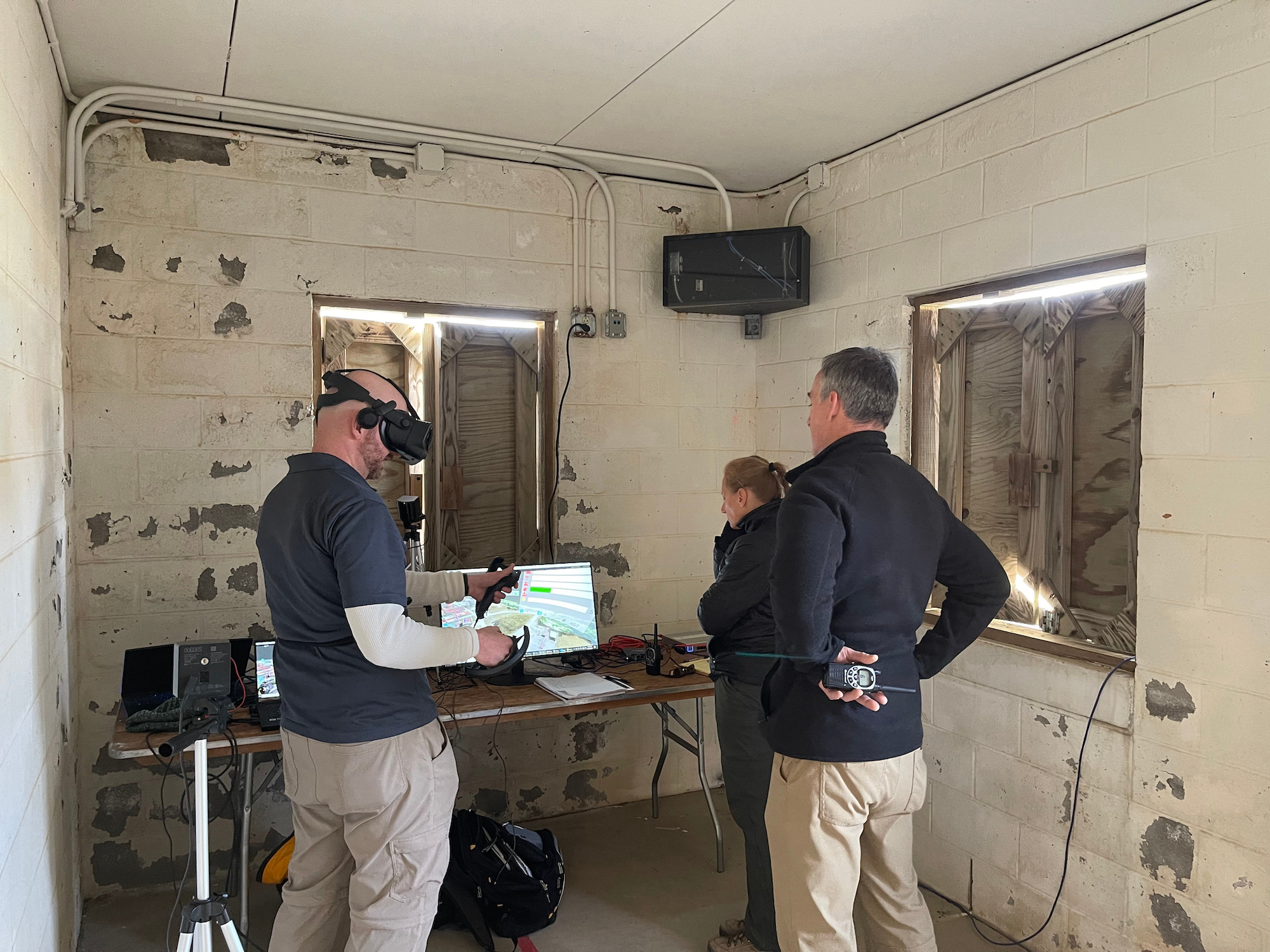

For the person directing the swarm, the entire array of robots appeared as a virtual reality strategy game, mapped onto the real world.

Wearing a Microsoft VR headset, the operator interacted “with this 3D VR interface that has what’s called a sand-table view,” says Clark. “It can be very similar to the sort of God’s Eye, real-time strategy game view, where they see all the platforms laid out over a 3D map of the environment. When something is detected, they’ll get an icon geolocated to the space. So if one of the platforms detected a hazard right outside of the building, they’d see a red flashing icon appear in space where that belongs.”

With the headset on, the operator was able to assign the swarm missions and see what the swarm had already scouted, but they was not giving direct orders to individual drones. The swarm AI, receiving orders and processing sensor information, was the intermediary between human control and the movement of robots in physical space.

At present, when a squad wants to use a drone to scout an area, it takes a dedicated pilot controlling it by tablet to see and direct the robot. The new approach has drawbacks and advantages: Because the operator’s VR headset blocks out the surrounding world, the human operator is vulnerable and oblivious to their immediate surroundings, except as they are displayed inside the headset. At the same time, the human operator is directing the actions of dozens of robots, shifting the one-to-one pilot-to-drone ratio drastically. Provided the human swarm operator can stay safe and the network can stay functional, the drones can capture useful information and relay it to nearby soldiers in the field. The new technology allows for a tremendous shift in what can be known about a battlefield in real time.

How the swarm operated

The physical drone models included custom drone planes made by Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab. In the swarm, their role was primarily passing over the entire training area and initial mapping, though the swarm also directed them to provide camera coverage as needed. On the ground were small wheeled robots made by Aion Robotics. In between were four different types of quadcopters, including 75 3DR Solo drones, light-show drone models from UVify, and two sizes of quadcopter by ModalAI.

[Related: These augmented-reality goggles let soldiers see through vehicle walls]

All of the robots involved were either commercial models or custom models built from commercial, off-the-shelf parts. This was not a swarm built to military specifications—these were commercial, hobbyist, and custom-built machines working together through dedicated software. That keeps the cost of the swarm down to about $2,000 for each robot in it.

These six types of robots reported telemetry information to each other, letting the swarm know where each part of the whole was in space. That shared information let the swarm collaborate on flight paths in real time, moving pieces into place as needed while avoiding collision.

“We work hard to do some processing [of sensor readings] on platforms, so we don’t need to send a lot back on the network,” says Clark. “So we never send back a raw picture. We send back, ‘ah this picture is a door’ or ‘this picture is a hazard’ or ‘a source of intel.’ That processing happens on board. We just send back a notification.”

[Related: Why the Air Force wants to put lidar on robot dogs]

Automated processing makes swarm interactions possible. It can also, depending on the nature of what is processed, come with a significant risk of error.

Each of the robots was equipped with a little LTE modem, and to ensure the robots were communicating with each other and the human operator, the team set up an LTE cell tower, like the kind that regularly processes cell phone signals. This let the swarm share location to Android Tactical Assault Kit (ATAK), a program that runs on phones and lets soldiers in the field receive and send battle-relevant information.

“During the field exercise, as a matter of convenience, we had safety spotters out on the range looking for unsafe conditions or flyaways, and all of their phones were receiving all of the swarm traffic and their phone would vibrate and warn them if something got too close to them, because it’s too hard to track all of them in the air at the same time,” says Clark.

By only filtering the proximate drone location to people in the field, the swarm shared only what the observers needed to immediately know. In a real-life scenario, with swarms moving in support of battle, soldiers will at most need to know if a nearby drone is friendly, and won’t want to spend a lot of time sorting out where exactly the rest of the swarm is.

As the Pentagon expects future battles to take place in massive urban environments, getting more situational awareness could mean the difference between squad survival and ambush.

Watch a video from the human swarm operator’s perspective below: