An unexploded bomb is a terrible threat, and the Air Force is investing in armored vehicles with powerful lasers and robot arms to safely clear them off runways. In February, the service branch announced that in the fall of 2022 it will start fielding these new bomb disposal vehicles. These machines, and the people inside them, will work to ensure runways, both at home and nearer to combat abroad, are able to launch and receive aircraft without sending pilots into an accidental inferno on the ground.

These vehicles are called “Recovery of Airbase Denied By Ordnance” or “RADBO,” and they are based on MRAPS, the Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles that the Pentagon used for patrols in Iraq and Afghanistan. MRAPs are already built to ensure the survival of their passengers against explosives, with special v-shaped hulls directing the blast force away. There is enough of a surplus of MRAPs that NASA has some, and the military has offered many to police departments as overqualified crowd control vehicles.

Bombs can end up on runways for a host of reasons. The most dramatic are enemy attacks, with cruise missiles cratering the surface from afar, or hostile air forces flying close enough to try bombing an airbase from the sky. Ground attacks, too, can place explosives on pavement, like army artillery or bombardment by nearby mortars.

Also possible, while less flashy, is the Air Force accidentally having a loose bomb on takeoff or landing end up on the tarmac. In every instance, clearing the runway of explosives, however those explosives got there, is essential for returning the runway to service so aircraft can safely take off and land.

An explosion on a runway is an immediate problem, and provided the debris can be cleared, has an easy fix: repair the runway, and continue moving. An unexploded bomb is more complicated, as the explosive ordinance disposal (EOD) crews may not know if the bomb is a dud, or if the process of clearing it will cause it to explode.

“Current procedures require an EOD technician in a bomb-resistant suit to place a charge on unexploded ordnance or to attempt to defuse it, a procedure that is ‘time- and manpower-consuming’ as well as highly dangerous,” an Air Force Life Cycle Management Center spokesperson told Air Force Magazine in February.

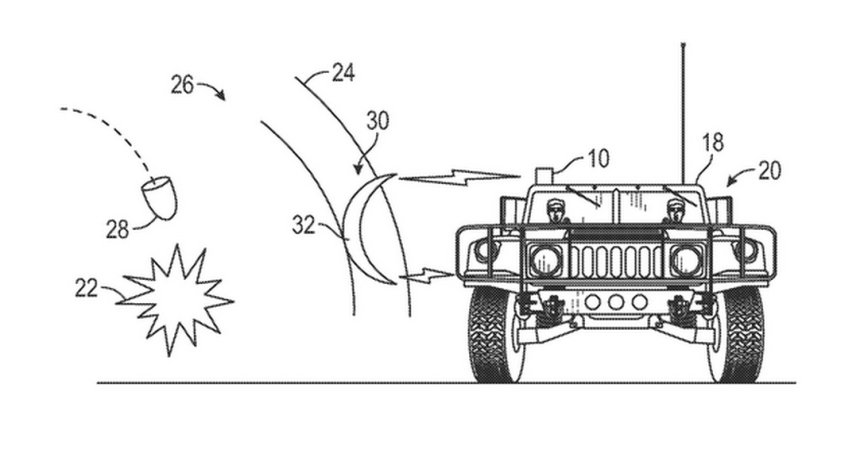

Instead of sending a highly skilled human in a protective suit to defuse a bomb by hand, what RADBO proposes is: What if a truck shot it with a laser instead? The RADBO MRAP will mount a three-kilowatt Zeus III laser and a robotic arm, in a vehicle that weighs approximately 18 tons.

Together with the Army, the Air Force started exploring the laser part of RADBO vehicles in 2015, with a vision for both battlefield and air base use cases. As a 2015 press release noted, RADBO vehicles were also proposed for immediately clearing the live fire area after a practice bombing run, allowing more pilots to train for attack runs without having to wait for the target area to be reset.

With enough power and time, a laser could burn through a bomb casing, blowing up the explosive from a safe distance for humans and vehicles. The robot arm on the vehicle is there to allow crews to investigate craters without physically getting in them, and to move bombs to places where it is better to detonate them.

Much of this work can be done, in part, with human crews or ground robots, but the process is time intensive. The RADBO vehicle as designed becomes a holistic answer to clearing potentially explosive detritus from a space it should not be.

For now, the Air Force envisions RADBO vehicles as better safety equipment at existing bases. In the future, a conflict could call for the creation of new runways closer to the front of that conflict, and RADBO vehicles could ensure those ad-hoc and rapidly assembled airstrips remain operational even in the face of hostile attacks.

“We have an air superiority mission,” said Tony Miranda, RADBO program manager. “If we are in a high threat environment, and there are unexploded ordnance on the airfield, maintainers can’t take care of the aircraft and the aircraft can’t get off of the runway. These RADBO vehicles will be utilized by Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) technicians to detonate the unexploded ordnance (UXO) from a standoff range, so we can get back to the business of flying planes.”

In the meantime, having the vehicles on hand can turn an dropped or otherwise inadvertent unexploded ordnance on a base into an imminently solved problem, instead of a hazard that persists for weeks, years, or even decades.