The first robot to kill a person with a bomb while under police command in the United States was a Remotec Andros Mark V-A1. Confirmed by the Dallas Police Department this morning, the make and model of the robot answers just one question concerning a novel use of force. Thursday night’s circumstances in Dallas were exceedingly unusual, but as with all firsts, there’s a chance that this will set a precedent for the future. And the biggest danger isn’t the bot, it’s the bomb.

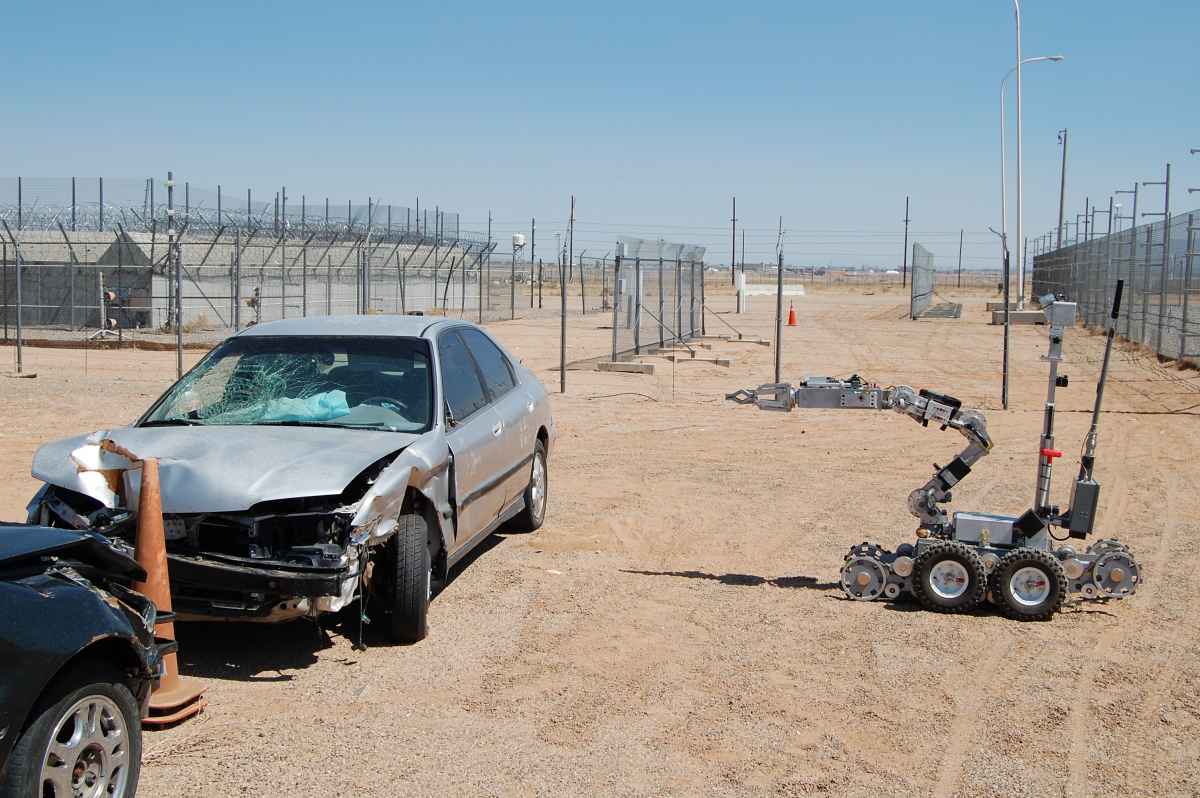

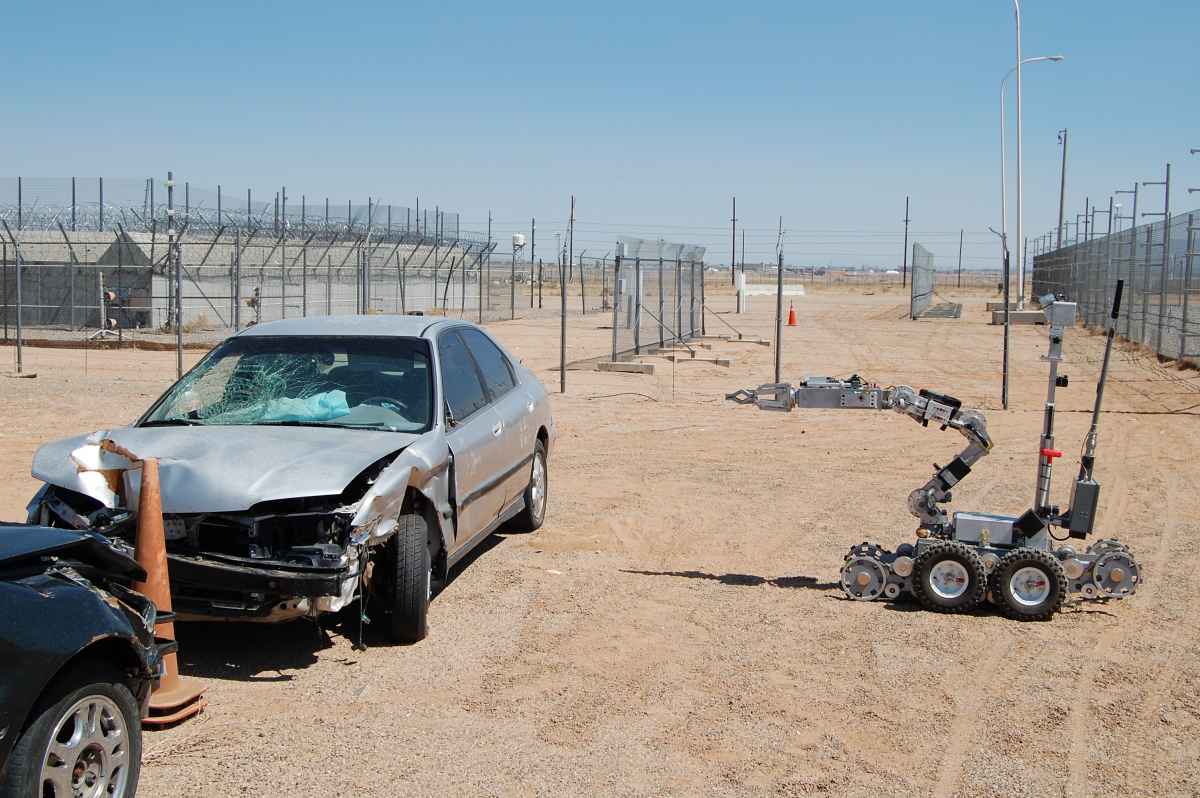

The robot is a remotely controlled vehicle used for explosive ordnance disposal. The Andros is controlled by fiberoptic cable, wire, or wireless remote. It has a camera and a two-way microphone, and it’s been used for negotiation before. Dallas police claim they negotiated with the suspect before using the robot.

The Andros isn’t an autonomous machine. It was a delivery vehicle for a bomb, albeit an unusual one. Robot war theorist, author, and Popular Science contributing editor Peter W. Singer notes that American troops on patrol in Iraq equipped a relatively cheap, $8,000 bomb squad robot with explosives and used it against insurgents. The Andros is significantly more expensive, at roughly $200,000 in today’s dollars. Cost isn’t the only factor, but it’s one of them, and having a robot to dispose of multiple suspicious packages and potential bombs is generally a better use than turning it into a one-use bomb cart.

There are many lethal weapons in the arsenals of law enforcement agencies, from handguns to shotguns to semi-automatic rifles, but explosives intended to kill are notably absent. (Less-lethal flash-bang grenades are still horrific when they hit toddlers in the face).

Last week, Dallas police jury-rigged the explosive they used, and it killed just the specific person they were targeting.

The rough analogy that best fits, I think, is how police use helicopters. New York police first gained a helicopter in 1948, and over the next several decades other many police departments in the United States followed suit. Helicopters were used then much as they are now: for surveillance, patrol, and watching things happening on the ground.

In 1985, the Philadelphia Police Department decided to use its helicopter for a different end. After an exchange of gunfire, police used a helicopter to drop two small bombs on the compound of the radical group MOVE, which was a rowhouse on a block in Philadelphia. The bombs burned the compound down, as well as 65 other nearby houses.

The MOVE bombing didn’t diminish police enthusiasm for helicopters, but it also didn’t encourage other departments to use them as bombers again. It’s entirely possible that the lesson police draw from a bomb-equipped Andros in Dallas is simply that it was a weird, extreme case, that called for a unique attempt to end a standoff.

Or it could become part of a police force’s arsenal. In an interview with CNN, the New York Police Department commissioner said he “had no problems with it as it was used in Dallas,” though he also qualified it noting the specific circumstances involved.

Police forces typically adapt to attacks on police by changing what they do, often in ways that increase their firepower.

SWAT teams, the heavy-armored, aggressive police units that often travel in armored cars or MRAPs, were born as a response to sniper attacks on police, and are now a standard part of police forces across the country.