On Wednesday, European regulators announced that dangerous blood clots in the brain and torso are an extremely rare side effect of the COVID vaccine manufactured by AstraZeneca, but still recommended the continued use of the drug.

“The reported combination of blood clots and low blood platelets is very rare, and the overall benefits of the vaccine in preventing COVID-19 outweigh the risks of side effects,” the European Medicines Agency announced in a statement.

The shot, which has not been approved for use in the United States, has been widely distributed in the European Union and a handful of other countries. No similar side effects have been observed in any of the vaccines being administered in the US.

According to the EMA, “Most of the cases reported have occurred in women under 60 years of age within 2 weeks of vaccination. Based on the currently available evidence, specific risk factors have not been confirmed.”

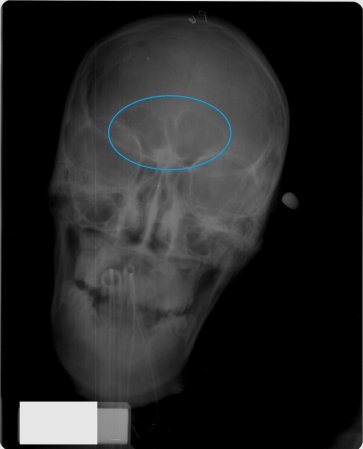

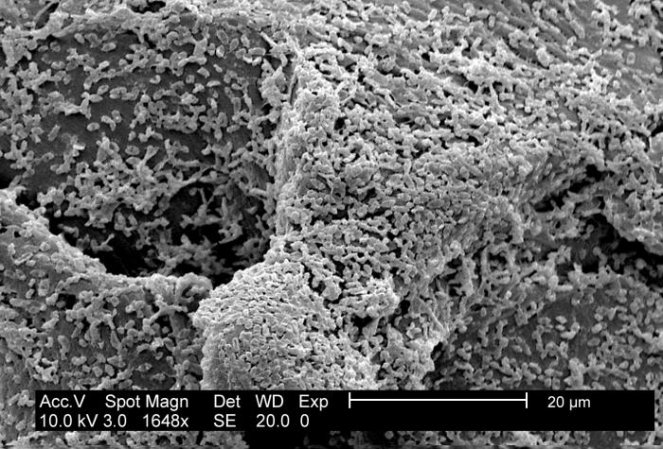

The EMA reported that it had documented 86 cases of thrombosis, or blood clotting in veins deep in the body, in about 25 million vaccinated people. 18 of those cases were fatal. In other words, fewer than one in a million people who received the vaccine experienced dangerous blood clots. It’s also not clear that all of those deaths were caused by the vaccine–the EMA has previously noted that thousands of Europeans die of this clotting every year.

“This is a tough one,” says Sean O’Leary, who specializes in pediatric infectious diseases and vaccine hesitancy at Children’s Hospital Colorado. “We are in the midst of the deadliest pandemic in a century. You can see, from a societal standpoint, why Europe is saying the benefits outweigh the risk. By any measure, [the clotting] is an extraordinarily rare event.”

In the US, about 2 in every 100 people diagnosed with COVID have died. But, says O’Leary, balancing those risks creates a hurdle to public health communication.

“None of us are very good at risk interpretation,” he says. “Whether it’s a risk of one in 100,000 or one in 10 million, those aren’t very meaningful to people. It’s the fact that it could happen” that frightens people.

The recommendation is also complicated by the fact that we don’t know why the vaccine appears to carry this risk. Many of the clotting cases are accompanied by low levels of platelets in the blood, which would normally promote clotting, and that “ combination … immediately raises the possibility of an immune reaction,” Sabine Eichinger, a blood specialist at the Medical University of Vienna, told Science Magazine in March.

According to the EMA, the side effect appears to resemble a rare disorder caused by the blood thinner heparin, in which the immune system produces antibodies that attack platelets. That disorder is treatable, and the EMA believes the same will hold true for the side effect.

The EMA initially opened an investigation into blood clotting in November 2020, after Danish authorities paused the rollout over safety concerns. In March, more European countries, including France and Sweden, stopped giving AstraZeneca’s shot over the same concerns, and rising vaccine hesitancy. At the time, the EMA wrote in a statement that the number of blood clots “overall in vaccinated people seems not to be higher than that seen in the general population.”

But the restrictions have continued. Last Friday, New Zealand suspended the use of the vaccine for women under the age of 60. France has similarly restricted its use to people over the age of 55.

AstraZeneca has not yet submitted its vaccine for FDA approval, following a March media debacle where the company released misleading data from its US trial that inflated the shot’s efficacy a few percentage points. The company says that it plans to submit the results soon.

That US trial found no increased risk of blood clots, according to the company—it actually said that more of the clots were seen in trial participants who received the placebo.

It’s not clear what role, if any, the European findings might play in the American approval process, since these events have been documented outside of clinical trials. A member of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee said over email that he was not allowed to comment on a vaccine that had not yet been submitted for an EUA.

There is something of a historical parallel here, O’Leary points out: in the ‘90s, the US pulled approval for a vaccine for rotavirus, a life-threatening gastrointestinal disease that mostly affects children. The vaccine was found to be highly effective at preventing hospitalizations, but once it was in widespread use, cases of an intestinal blockage began popping up in the vaccinated.

Few children died of rotavirus in the US, so while it was clear that “the benefits of the vaccines probably outweigh the risk, the US made the decision that … we hold safety to such a high standard that we will not recommend the use of the vaccine,” O’Leary explains. “But they said that this is such a great vaccine that it should be used in parts of the world where the burden of rotavirus is high, and there are thousands of children dying every year.” Other countries, however, followed the US’s lead, and the drug went out of production.

Given that the US has already secured enough vaccines from other manufacturers to cover its entire population, it’s not clear if it will follow Europe’s lead in approving AstraZeneca. But if it doesn’t, it could set the tone for other countries that haven’t had the financial might to buy up millions of other doses.

Correction: This article previously stated that few children were affected by rotavirus in the US—many were infected, but few died.