The H1N1 influenza virus, one of the circulating culprits that causes seasonal flu, appears to be a direct descendant of the virus responsible for the catastrophic 1918 flu pandemic.

An international team of researchers uncovered a rare set of three human lung tissue specimens dating between 1900 and 1931, preserved in the Berlin Museum of Medical History and the Natural History Museum in Vienna, Austria. By analyzing these samples, researchers were able to complete the genome of the flu virus from early on in the 1918 pandemic. When they compared it to today’s H1N1 swine flu, they found that every element of H1N1’s genome could be directly descended from that initial strain.

If this theory is correct, it would mean that single virus strains can evolve on their own to take on new characteristics and even infect new species, as opposed to the predominant theory that viral strains evolve through different viruses sharing their genetic codes. The findings were published on Monday in Nature Communications.

“The subsequent seasonal flu virus that went on circulating after the pandemic might well have directly evolved from the pandemic virus entirely,” study author Sebastien Calvignac-Spencer, an evolutionary biologist at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin, told HealthDay.

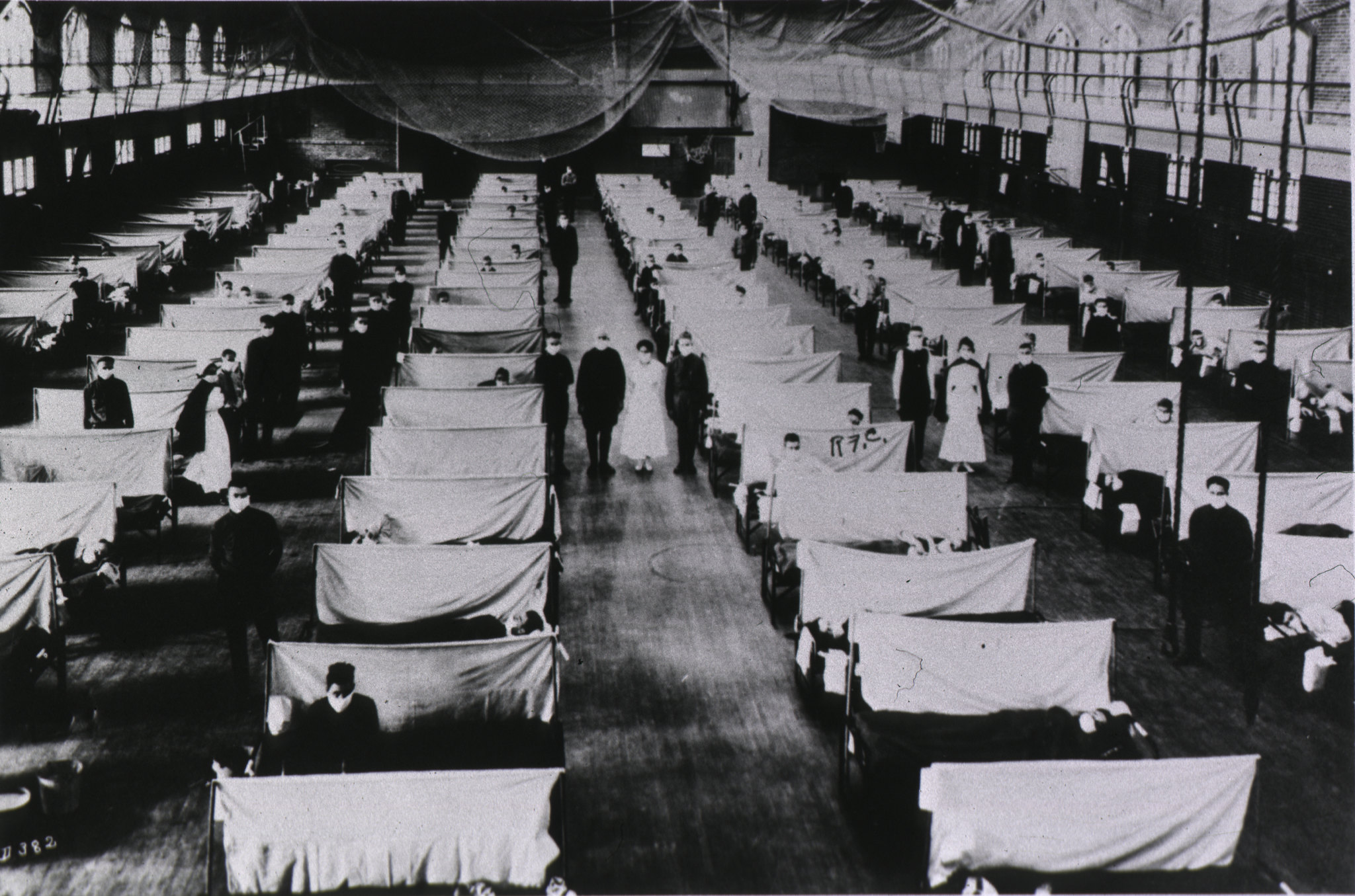

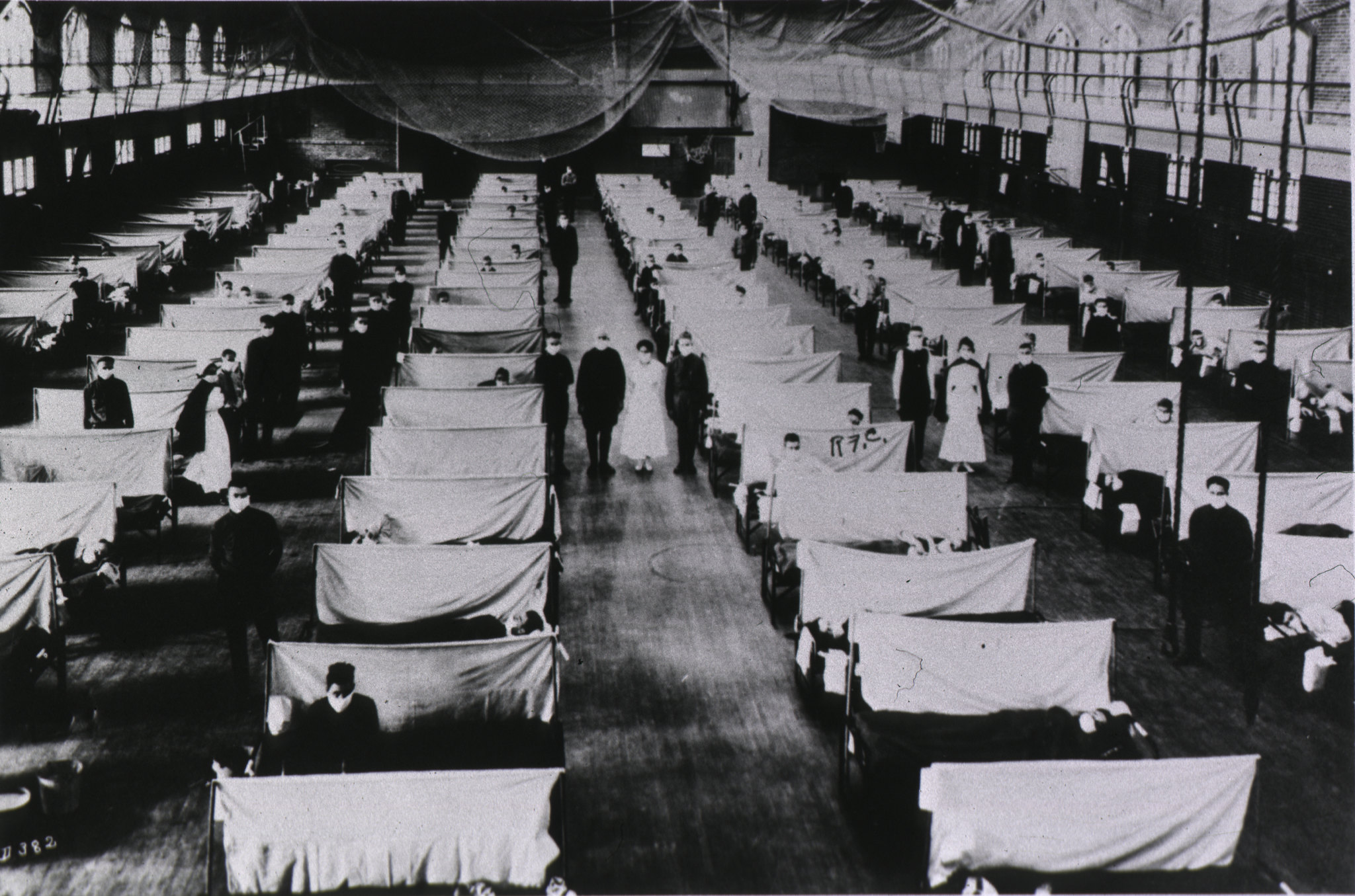

The 1918 influenza pandemic, also known as the Spanish flu, was the second most deadly pandemic in recorded history, just after the bubonic plague, and estimates put the death count between 17 million and 100 million people. But despite the immensity of this pandemic, the origin of this outbreak is still unknown. The first reported cases came from the US, but it’s possible that earlier infections circulated undetected for weeks or even months.

[Related: An exhaustive account of how the flu destroys your body]

Due to limited availability of tissue samples, genetic analysis of the 1918 influenza virus is tricky. “When we started the work, there were only 18 specimens from which genetic sequences were available,” Calvignac-Spencer said in a statement. “There was also no genome wide information about the early phase of the [1918] pandemic, so any new genomes documenting new locations and periods can really add to our knowledge of this pandemic.”

Research in this vein can help health experts understand the progression of viral pandemics. The authors of this study believe that their findings could also explain the origins of the H1N1 swine flu outbreak in 2009. After all, the 1918 influenza was known to have entered the pig population during that pandemic, study author Thorsten Wolff, head of influenza and respiratory virus research at the Robert Koch Institute, said in a statement. It’s possible the 2009 outbreak was that strain finding a way to jump back into humans.

But due to the small sample size of these lung specimens, the authors of the new study acknowledge that their findings cannot say anything definitively about the 1918 influenza virus’s evolution. “Spanish influenza is still a riddle in virology because there are many open questions that we still don’t know the answers to,” Wolff added.