Life started around 3.8 to 4.1 billion years ago. For a large part of that time, organisms on Earth were simple and evolution was slow. But something remarkable happened around 550 million years ago. Increases in calcium and oxygen in the environment led to the development of the inner ears and balance organs (the vestibular system). Another 165 million years after that, some organisms—including those that would evolve into human beings—were lured onto land, perhaps to get a better view.

Jumping forward to around 2,000 years ago, the Greek physician Hippocrates wrote that “sailing on the sea proves that motion disorders the body.” Indeed, the word “nausea” is derived from the Greek “naus,” relating to ships, sailing, or sailors.

About 65 percent of people suffer from motion sickness, women more often than men, with peak sensitivity around the age of 11. But why is it so common?

Normal response

Motion sickness happens when there is a mismatch between what your eyes are telling your brain and what your inner ears sense as motion.

In a car, this means that if you look down at a phone, a newspaper or a stationary object, your eyes are telling your brain that you’re not moving. But your vestibular system (the organs of balance in your ear) is telling your brain that you are moving. This is the reason that having a good view of the road ahead and looking at the horizon prevents motion sickness: What your eyes see matches what your body senses. Experiencing motion sickness in a moving vehicle tells us that our vestibular system is working properly].

Humans aren’t the only species to get motion sickness. Dogs, cats, mice, horses, fish, amphibians, and many other animals experience motion sickness, even if symptoms vary slightly between species.

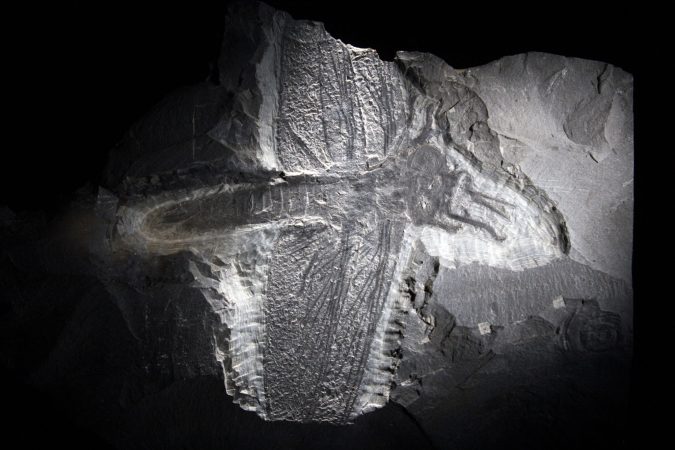

If you look at these animals on a tree of life, they are all linked to the hagfish and lamprey as the lowest common ancestor. The hagfish has one vestibular channel, while the lamprey has two. Bony-jawed fish, such as sharks, came along shortly after the hagfish and lamprey. Like us, they have a three channelled vestibular system.

So have we inherited our sensitivity to motion from our fishy friends, becoming more susceptible to it as we became more complex over time? The answer is not that simple. Crabs, lobsters and crayfish all have highly developed vestibular and eye-control systems, which evolved independently and earlier than fish, some 630 million years ago. And there’s anecdotal evidence that they, too, experience motion sickness. So seasickness is not simply an inherited quirk—it seems to be a sign of something working as it should.

But what triggers motion sickness in other species, and how could it be an evolutionary advantage? To answer this, we need to look at what kinds of motion exist in natural environments.

Beyond cars and boats

Oceans. Waves don’t just exist above the surface, they are felt below the surface too, at levels between 0.16 and 0.2Hz, and affect sea life in several ways. Indeed, some fish have been shown to move out to calmer water during storms.

Seasickness could be the way a fish’s body lets it know it’s in danger. Interestingly, the amount of motion a human can withstand without getting sick is very close to that for a fish (0.2Hz), which also corresponds to the frequency of wind-generated waves. This could be a coincidence, but it is more likely that it points to a deep connection that still exists between the human body and the ocean.

Trees. Trees protect many animals, including our recent ancestor, the chimpanzee. But like the ocean, trees can be turbulent. It’s possible that evolution favored the species that kept their aversion to motion, as they moved to lower, less mobile branches, so reducing their risk of falling to their death. Humans may think they’ve left trees and swaying branches behind, but the tall buildings we like to live and work in have a tendency to sway silently in the wind much as trees do, with some people sensitive to motion sickness reporting dizziness, loss of concentration, drowsiness, or nausea.

Our vestibular and other systems have evolved over millions of years for walking, so it’s not that surprising that boats, cars, camels, and, more recently, hyper-realistic VR head-mounted displays cause motion sickness. Our sensory systems have not had time to adapt to new technologies and environments.

Difficult to cure

Any solution to motion sickness is fundamentally at odds with millions of years of evolution, which is why it is so difficult to remedy.

Many take prescribed medication such as scopolamine to cure motion sickness, but as well as having unpleasant side effects, drugs prevent you from becoming used to the environment, meaning that you continue to rely on the pills. (Some people take herbal remedies, but these have mixed results.)

The most effective solution to motion sickness is to slowly get used to the environment. For example, someone who spends a lot of time on boats is less likely to get seasick, hence the phrase “sea-legs“.

Motion sickness appears to be a normal response in all healthy humans. An ancient subconscious mechanism for genetic fitness has been perhaps mislabelled as a sickness. A motion “reflex” may be a better description.

Spencer Salter is a PhD Researcher, National Transport Design Centre, Coventry University. This article was originally featured on The Conversation.