A male gorilla can weigh more than 300 pounds and flash fearsome two-inch canine teeth. But at the end of the day, he’s probably a sweetheart.

“A lot of what you hear about gorillas is they’re big and aggressive,” says Cambridge biological anthropologist Robin Morrison. In reality, though, they’re massive, peaceful vegetarians. “They’ve been called the cows of the forest,” she says.

Gorillas are not only docile, but also incredibly collaborative. And according to a new study published this week, the primates have rich social lives that parallel the hierarchical structure of human societies wherein close-knit groups (families, for example) are nested, like Russian dolls, in increasingly larger communities. Like people, individual gorillas often form lifelong bonds with each other, and also cooperate with other social groups to which they do not belong, according to the findings published in the journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“In humans we’ve got families, but we also have extended families and friend groups and communities,” says Morrison, a co-author of the paper. “We wanted to know, what are those like for apes?”

To answer that question, Morrison and her colleagues analyzed six years of observational data collected at two research sites in the Republic of Congo, mostly at the Mbeli Bai clearing, where scientists have studied the primates for decades. At the sites, researchers watched, identified, and studied western lowland gorillas from platforms established at the edge of forest clearings where abundant, protein-rich vegetation draws the animals to feed for hours at a time. “It’s a very slow process,” Morrison says. Then, the researchers used statistical analyses to quantify the community structure of the populations.

Scientists already knew that gorillas live in small “families” sometimes known as troops that tend to be made up of one dominant male, called “silverbacks,” and several females and their offspring. But in their analysis, Morrison and her colleagues were able to quantify and map the structure of two, hierarchical social tiers—present in both communities they examined—for the first time.

The first social tier above the tight-knit groups consisted of about 13 gorillas, on average, and is akin to human extended families made up of uncles, aunts, cousins, and grandparents. Beyond that, researchers observed a further social tier made up of about 40 gorillas, that spend time together without necessarily being biologically related, like a village or tribe. In fact, the researchers found that 80 percent of those close associations they detected were between distantly related or even entirely unrelated silverbacks.

The gorillas’ diet may help explain why it might be advantageous for them to develop complex societies. Western gorillas search and seek out a wide array of plants that rarely produce fruit. Early on in life, family groups help train the young on how to forage. Later, the researchers surmise, long-term bonds and networks could help larger social tiers remember when certain trees produce fruit or where to find them.

“This underlying social structure is there. It brings up so many questions of why,” Morrison says.

Other research efforts in recent years have also explored the social dynamics of gorillas. In 2018, researchers studying mountain gorillas in Rwanda found interactions between familiar social groups were significantly more peaceful than those involving unfamiliar groups. In February, another group analyzed five years’ worth of data on western lowland gorillas and documented dynamic, unaggressive social systems that featured play among its young and the protection of fatherless infants.

This week’s paper suggests humankind’s social systems may not be so idiosyncratic. Although some scientific theories posit that the evolution of a sophisticated “social brain” is unique to hominids, the discovery of the complexity of gorilla societies suggests the social organization observed in humans may have evolved far earlier than previously believed. Instead of developing in humans 100,000 or 200,000 years ago, Morrison says, social hierarchies may have emerged somewhere closer to 8 million or 10 million years ago.

“If we shared it,” she says, “that suggests it’s something quite ancestral.”

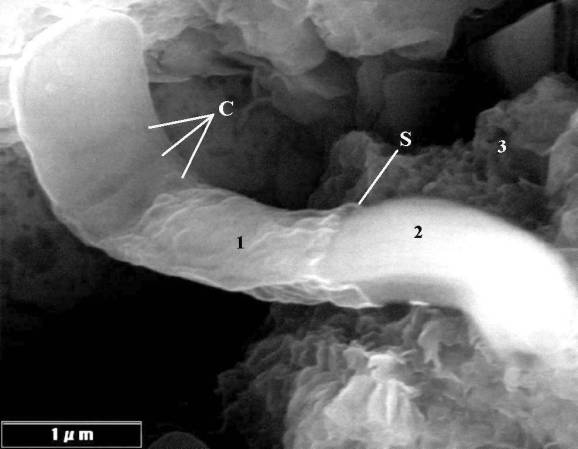

![Science Has Now Created Square Ice [Video]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/MXJB5ZWEASBNLCAKMMIZO63HAQ.png?w=657)