This post has been updated. It was originally published on August 22.

On August 23, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) successfully landed on the moon on with the Chandrayaan-3 mission. India is now only the fourth country to successfully place a probe on the moon, and the first to land at the lunar south pole. Previous moon missions touched down on the moon’s equator. Scientists now hope to deploy a rover to send images and data back to Earth.

“India’s successful moon mission is not just India’s alone,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi. He added that the mission is based on a “human-centric” approach and its success belongs to all of humanity.

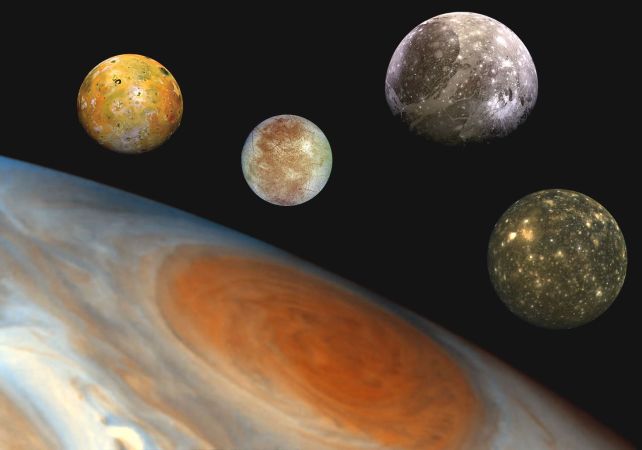

This has been a record week for space exploration—despite the obliterating crash of Russia’s lunar spacecraft on Sunday. The first Soviet and American soft landings on the moon happened all the way back in the 1960s, at the dawn of the Space Race. But it’s not easy to deposit a lunar lander—since those early successes, China has been the sole country to join Russia and the US in this feat.

“Very few countries have landed on anything. It’s just really hard, and everything has to work just about perfectly,” says Dave Williams, a planetary scientist who archives data of the moon at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

To start, spaceflight is a huge engineering challenge, and the moon is a particularly tricky target. Unlike Earth or Mars, our satellite has no atmosphere, so there’s nothing natural to slow down a spacecraft—no air for parachutes or gliders to use. The only way to get to the surface without crashing is a controlled descent, in which rockets lower the probe all the way down. Plus, the rocket engines must shut off at a precise moment so the craft doesn’t bounce back up off the lunar surface.

[Related: 10 incredible lunar missions that paved the way for Artemis]

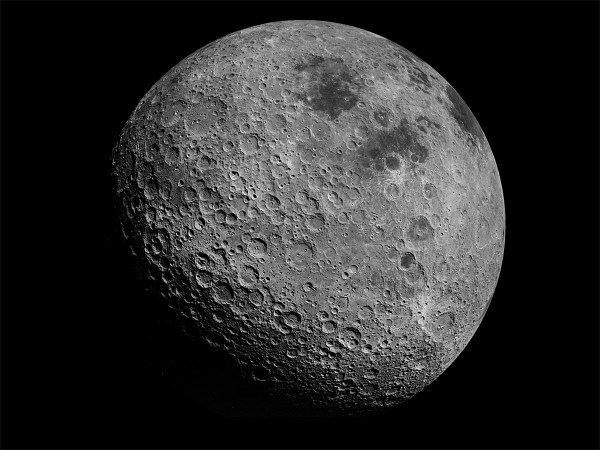

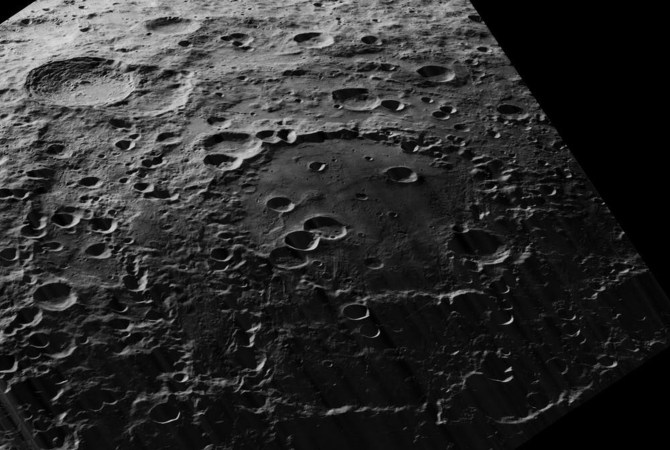

Making matters worse, although the moon doesn’t have oceans or cities, it still has plenty of hazards—namely, rocks and craters. Spacecraft have to navigate this terrain mostly on their own. The moon is far away enough from Earth command centers that a lander must be pre-programmed to do what it needs to for a safe landing.

This isn’t India’s first visit to the moon. The country’s lunar program began back in 2008, with a lunar orbiter and impactor in the Chandrayaan-1 mission. Chandrayaan-1 “played a vital role in raising awareness of space science among the general public,” says University of Florida astronomer Pranav Satheesh. “Many students, including myself, were inspired to pursue careers in space science and astronomy upon witnessing the success of ISRO’s programs.”

India made its first attempt at a soft landing with the Chandrayaan-2 mission in 2019. Unfortunately, that lander, named Vikram after the pioneering physicist Vikram Sarabhai, failed in the very last stages of its descent, crashing into the lunar surface. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter later spotted debris from Vikram’s crash as bits of metal strewn across the lunar landscape. The Chandrayaan-2 orbiter remained operational, however, and it continues to collect data in support of the current lunar landing attempt.

[Related: Why do all these countries want to go to the moon right now?]

Chandrayaan-3’s journey so far has been right on track. “Excitement about this mission is definitely palpable across Indian news media, WhatsApp chats, and even in everyday conversations for a lot of folks there,” says Pratik Gandhi, an astronomer at the University of California, Davis.

It entered lunar orbit on August 5, separated from its propulsion system on August 17, and even snapped a few teaser pics of the moon on August 18. As the lander descends to the moon in the coming days, the most dangerous moment is likely the landing’s second-to-last step: the fine braking phase. “The lander must kill all of its velocity and enter a hover state at about a kilometer above the lunar surface, at which point it must also decide in 12 seconds if it’s above its desired landing region or not and proceed with the touchdown accordingly,” explains science journalist Jatan Mehta. Russia’s Luna-25 probe, on the other hand, failed much earlier in its journey—which may be a sign of poor manufacturing or a lack of testing.

When the Indian lander touched down, it should have only been moving at about 4 miles per hour. But only the slightest deviations separate a crash landing from a controlled one. “The moon’s gravity, even though it is only about one-sixth of Earth’s, is still more than enough to destroy a spacecraft if it isn’t slowed down,” says Williams.

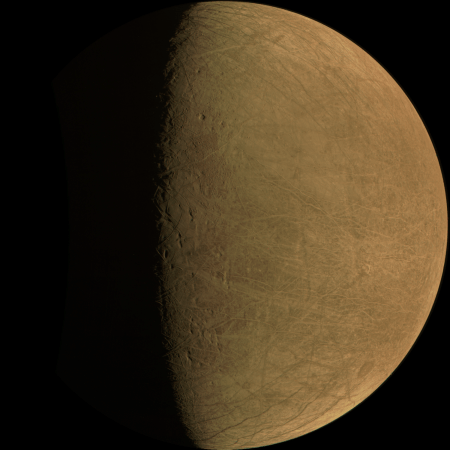

Some exciting science investigations are now in store for the spacecraft. Unlike any lander to come before, Chandrayaan-3 is targeting the moon’s south pole, where astronomers think there are deposits of water. Water is a crucial resource for future longer-term space exploration, both for astronauts to drink and for use as rocket fuel.

Chandryaan-3’s lander, also called Vikram, is carrying a small rover named Pragyan. Pragyan is only about 50 pounds—the weight of a medium-sized Goldendoodle—and will roam the lunar surface for about two weeks. It’s equipped with two spectrometers, which can measure the composition of rocks and soil, providing scientists with crucial information about this never-before-explored region of the moon.

The lunar southlands are also a key target for future installments in NASA’s Artemis program, paving the way for semi-permanent human habitation on our nearest celestial neighbor. In June 2023, India signed on to the Artemis Accords, an agreement for cooperation between countries in space exploration. Japan, another signatory of the accords, even has a rover in the works with India, with the goal of drilling into the lunar south pole in search of more water. All of these plans will have a better chance at fruition if India successfully lands on the moon.

“That India is one of the few countries to be able to build lunar landers means Chandrayaan-3’s success will be a critical part of being able to truly sustain the current global momentum for a return to the moon,” says Mehta. As more nations try to land on the moon, lessons from success—and failures—should help improve each next attempt.

Correction: A previous version of this article described the fine breaking phase as the last step of the landing. It is the penultimate step.