Jupiter’s moons are about to get JUICE’d for signs of life

Scheduled to launch in 2023, the explorer craft will probe Jupiter and three of its ‘ocean world’ satellites for habitable environments.

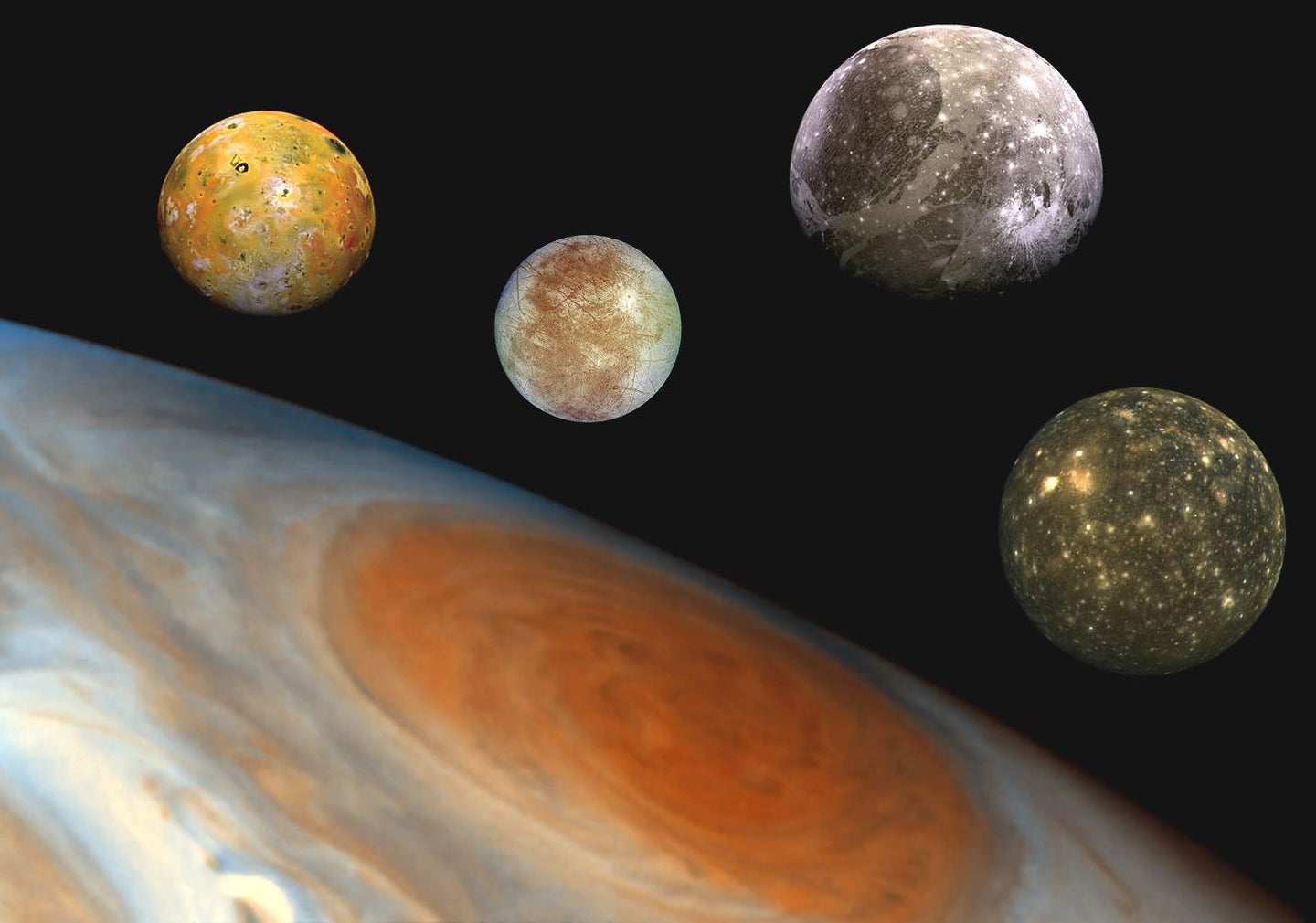

The European Space Agency will soon send JUICE, or the JUpiter ICy moons Explorer on a mission to scout out Jupiter and three of its 79 moons: Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede.

Scheduled to launch in April 2023, JUICE will blast off from an Ariane 5 rocket before embarking on a 7.6-year journey to reach the gas giant. Broken up by multiple gravitational assists—or pushes that help adjust a spacecraft’s speed and trajectory—from Venus and Earth, the explorer will carry some of the most powerful remote sensing and geophysical instruments ever flown to the outer solar system.

Last month, a 1:18 scale model of JUICE was employed at the ESA’s testing center in the Netherlands to try out one of the instruments, RIME, also known as the Radar For Icy Moons Exploration. RIME will use ice-penetrating radar and a 52-foot-long antennae to map the subsurface structure of these moons, up to about 5.6 miles down.

To test, the model was placed in a chamber lined with metal walls that blocked incoming radio signals and black, spiky foam coating that absorbed internal radio signals, or outgoing transmissions. This dichotomy helped the JUICE team simulate both the vast emptiness of space and the challenges the craft could run into during the mission.

“We don’t go to Jupiter all the time, in particular with the European Space Agency. So it’s a big mission for us,” says Olivier Witasse, project scientist for the JUICE mission. “The vision is really to understand whether [the target places] have what we call ‘habitable places’ around Jupiter.”

[Related: Researchers just measured Jupiter’s stratospheric winds for the first time—and they’re a doozy]

Mars has long been a hot research destination in the search for life, but icy worlds also have a legacy of promising conditions, Witasse says. “Twenty years ago, we discovered that there is a lot of liquid water underneath the surface [of icy worlds], and it wasn’t a big surprise.”

Space probes have been sent to study Jupiter since the early 1970s, but next year, JUICE will be the first to orbit around the planet’s moons. The mission, along with NASA’s JUNO which was recently extended through 2025, will bring the total number of Jupiter space probes up to 10, making it one of the most visited locations in our cosmic neighborhood.

One reason Jupiter and its satellites remain popular research destinations is because of their location in the Jovian System—known for its wide diversity of environments. By studying Callisto, Europa, and Ganymede, places which scientists already suspect harbor internal oceans, we could learn details that reveal new clues about the habitability of icy worlds.

Along with investigating conditions for how these habitable environments may have come about, the spacecraft’s main objective will be to observe Jupiter’s atmosphere and its magnetosphere, the region dominated by the planet’s magnetic field. But that’s where things will get tricky. In order to achieve mission success, JUICE will have to be able survive the physical strain of being so close to the gas giant.

“On the Earth, the magnetosphere shields us from charged particles from the sun,” says Michael Summers, a professor of planetary science and astronomy at George Mason University. “But on Jupiter, you’ve got a magnetic field that’s vastly larger than that of the Earth.”

According to Summers, Jupiter’s larger magnetosphere, or radiation belt, is so powerful that it can deal significant damage to the sensitive instruments a spacecraft carries onboard. To make sure this scenario is avoided, JUICE was specifically designed with Jupiter’s harsh environment in mind. Hundreds of pounds of thick aluminum shielding protects its most sensitive areas, and by never dipping below Europa’s orbit, it plans to stay outside of the planet’s main radiation belt for most of its mission operations.

But as with any experiment, the perfect scenario isn’t guaranteed to happen. “Even though we know we’re going to be surprised, and we try to think of all the things that might surprise us, we’re still surprised,” Summers says.

He says that a decade ago, a mission like JUICE would’ve been almost impossible to achieve. But with new technological advancements and the advent of similar deep-space projects like New Horizons, Summers is optimistic that the mission, while challenging, will be a successful one.

“Everybody that’s interested in science at all wants to know if we’re alone in the universe,” Summers says. And with JUICE, researchers expect the day we’re able to answer that question may be closer than we think.