Fossils can help us peer deep into the planet’s past. But that doesn’t mean that the interpretations of them are set in stone—in fact, experts often change their minds on what a fossil really is depending on new analysis and discoveries. In 2021, for instance, scientists decided that a 515-million-year-old fossil showed the earliest evidence of an animal group called the bryozoans, named Protomelission gatehousei. This discovery put the origin of the simple, filter-feeding colonies of aquatic invertebrates over 35 million years earlier than previously thought, putting their evolution around the same time as the Cambrian explosion. This period, taking place some 541-530 million years ago, marks the origins of most modern animal life.

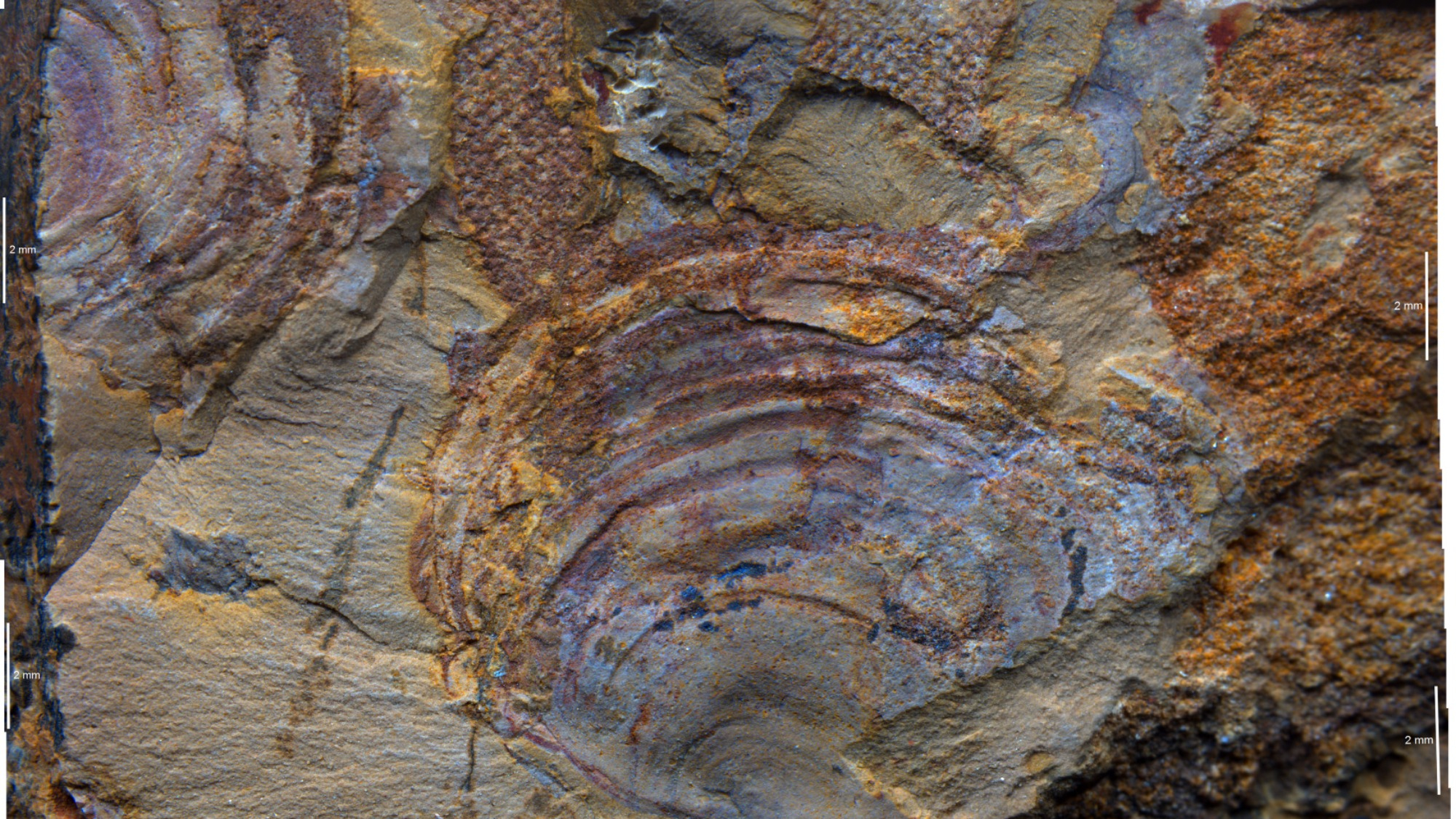

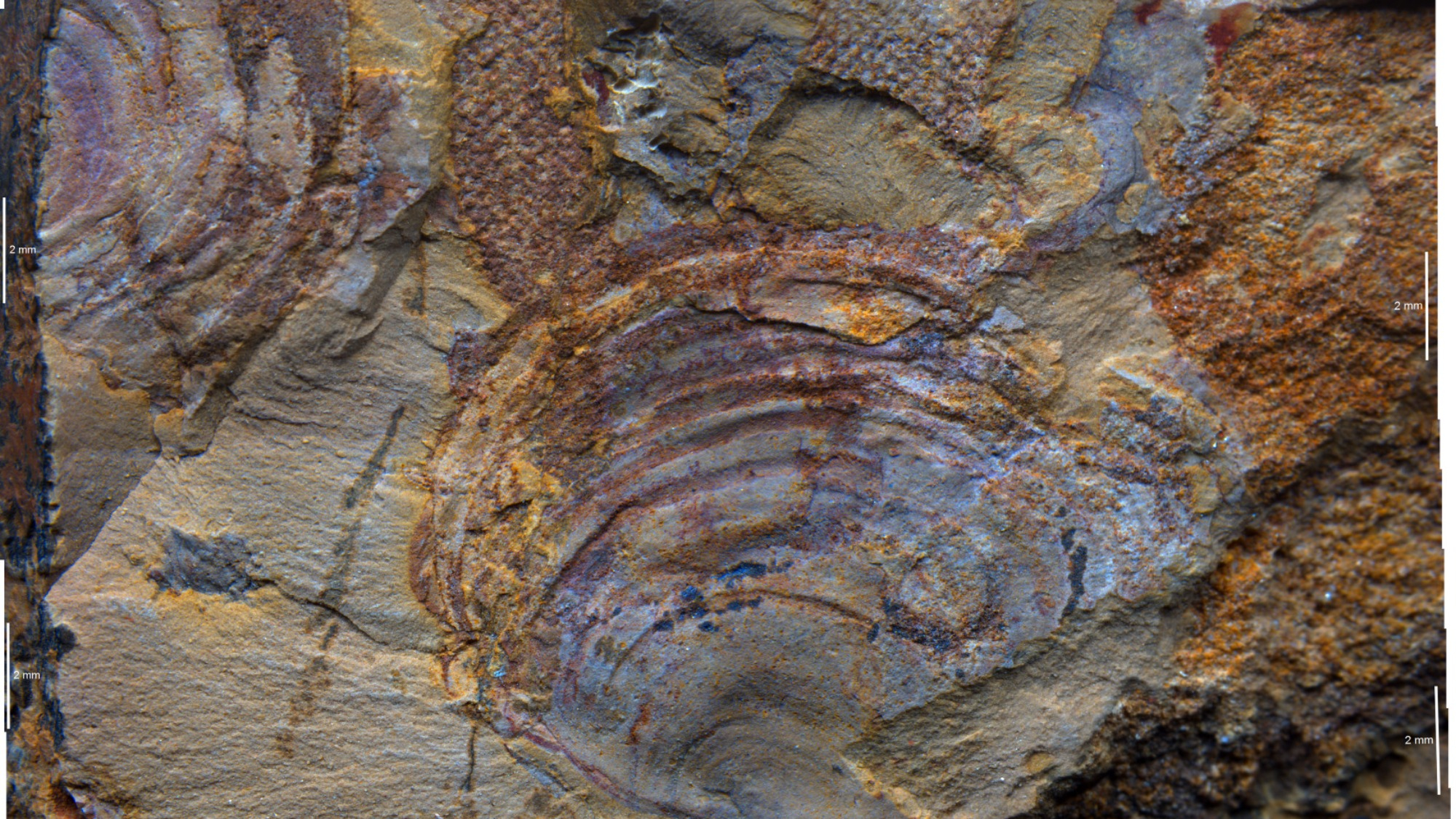

But, a second look at these fossils might indicate that’s not such a great fit after all. A new study published in Nature suggests that the Protomelission gatehousei fossil isn’t a bryozoan, or even an early animal after all. Experts from Durham University in the UK, as well as Yunnan University and Guizhou University in China determined, instead, that the fossil is just that of a dasyclad green algae.

[Related: Scientists find 319-million-year-old fossilized fish brain.]

For their research, the international team of scientists looked at a new specimen discovered in China’s Xiaoshiba Biota, known for well-preserved Cambrian fossils. The new, larger specimens make it appear that Protomelission probably isn’t a bryozoan, considering the fossils don’t have bryozoan type tentacles—instead they had little cactus-like projections. That’s not ideal for animals, Martin Smith, author of the new study and associate professor in paleontology at Durham, tells New Scientist, but it could be helpful for photosynthesis.

Even as dasyclad algae, the fossils are still pretty exciting. According to the authors, seaweeds were previously believed to be rare in the early Cambrian, but these fossils (and similar fossils called cambroclaves, which are abundant across the world but have uncertain origins) may actually point to a bit of an earlier seaweed renaissance.

“It could even be speculated that the diversification of seaweed could have contributed to the diversification of animals we see during the Cambrian,” Smith said in a release.

[Related: This fossil-sorting robot can identify millions-year-old critters for climate researchers.]

Of course, there’s still plenty of debate—Paul Taylor, a scientific associate at the Natural History Museum in London and author of the 2021 paper, argues that these new findings aren’t enough to nix their bryozoan theory. After all, tentacles are often made of soft tissue, he told The Guardian, which doesn’t fossilize well.

Either way, the fossils have quite a story to tell. On one hand, they could hold the key to bryozoan early roots. On the other hand, if the fossil is simple algae, it still shows how evolution still kept its “creative touch” even after the incredibly unique Cambrian period. Until more fossils are found, the algae versus animal debate isn’t history yet.