Pumpkin spice latte season is officially here. Starbucks baristas have been whipping up the popular beverage since they rolled out the fall menu at the end of August, even before the weather started to cool. But human PSL enthusiasts aren’t the only ones this autumn indulging in that warm mix of nutmeg, cloves, cinnamon, and pumpkin purée. One mycologist is brewing a special blend of pumpkin spice for a different kind of customer: fungi.

“Fungi are pretty closely related to animals,” says Matt Kasson, an associate professor of forest pathology and mycology at West Virginia University. “I thought, well, people have preferences. Maybe fungi have preferences for these pumpkin spices, too.”

That’s how Kasson, an avid supporter of team PSL, ended up with a lab smelling of pie. He created stacks of agar plates, or containers of gelatinous fungus food, full of pumpkin spice ingredients. Kasson’s fungi project, which he dubbed #WholeLatteDecay on Twitter, tests the ability of 17 species of fungi to grow on the unique conditions of spices, milk, sugar, and other ingredients commonly found in pumpkin spice lattes. His Twitter feed has been filled with similar fungus food experiments, such as Operation #MoldyTwinkie and #FungalPeeps. In time for fall, pumpkin spice lattes seemed like the perfect next candidate for a moldy takeover.

“This is all a ploy by me to get people interested in fungi and sometimes you have to use these things that people are familiar with and give them some kind of mind bomb,” he says. Fungi are well-known for decomposing all kinds of organic matter—from bread left out on the table, to over-ripe citrus on trees, to a forgotten cup of pumpkin spice latte—but it’s easy to gloss over how important they are. Prompted by his experiments, Kasson says, “people start asking questions like, ‘Oh, why did fungi grow here? Why did it grow there?’ ”

Earlier this summer, for instance, Kasson was tending to his garden in Morgantown, West Virginia when he encountered a problem: His patch of pumpkins were decaying. Wispy white strands of the soil fungus, Athelia rolfsii, which causes southern blight in plants, rotted the pumpkins. While this was disappointing for his crop, it also gave him an idea for his autumnal experiment back at his lab.

“I was witnessing my pumpkins kind of being dissolved in front of my eyes by this one fungus, and it got me thinking about how certain fungi really like pumpkins.”

[Related: Here’s the skinny on what actually flavors a pumpkin spice latte]

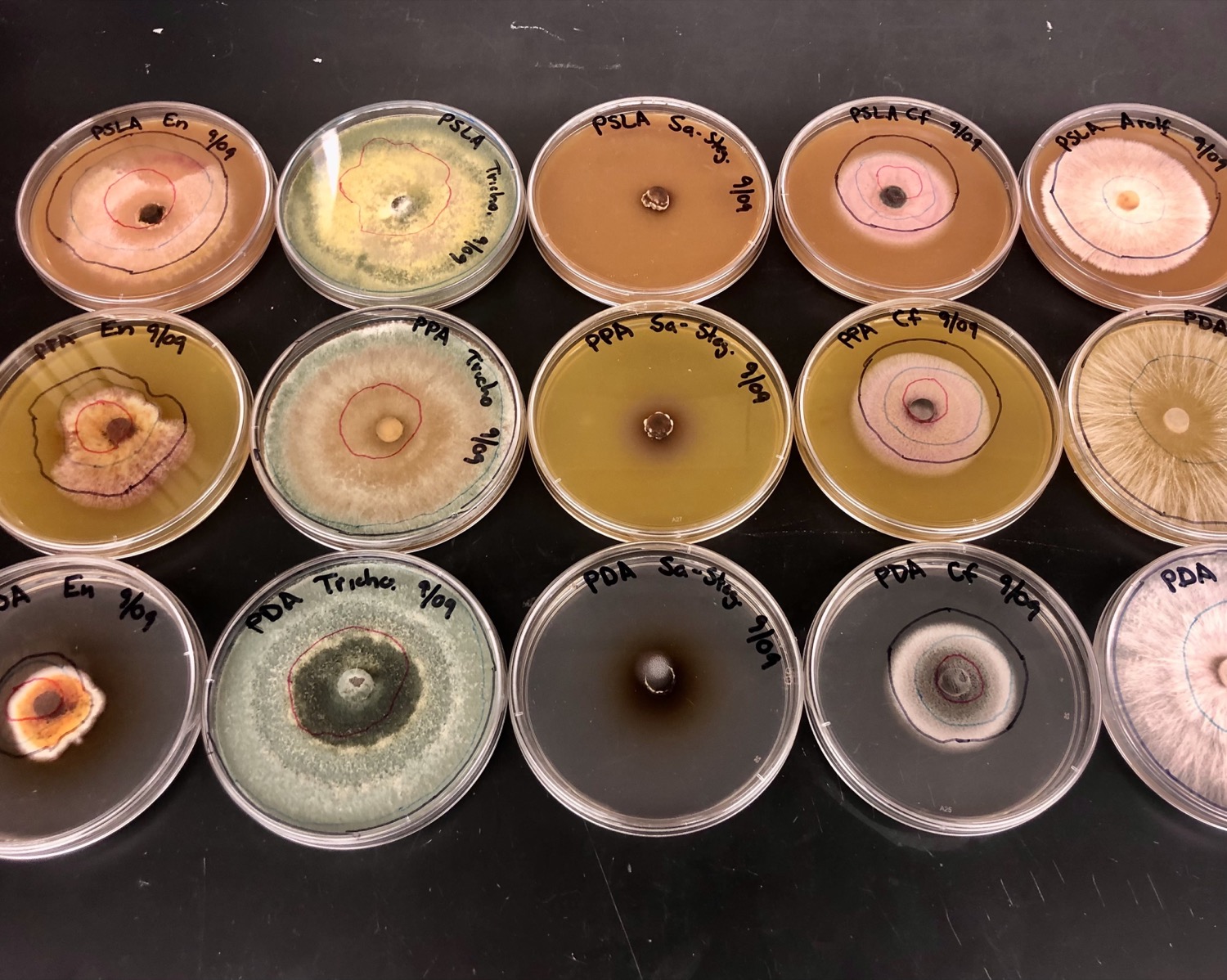

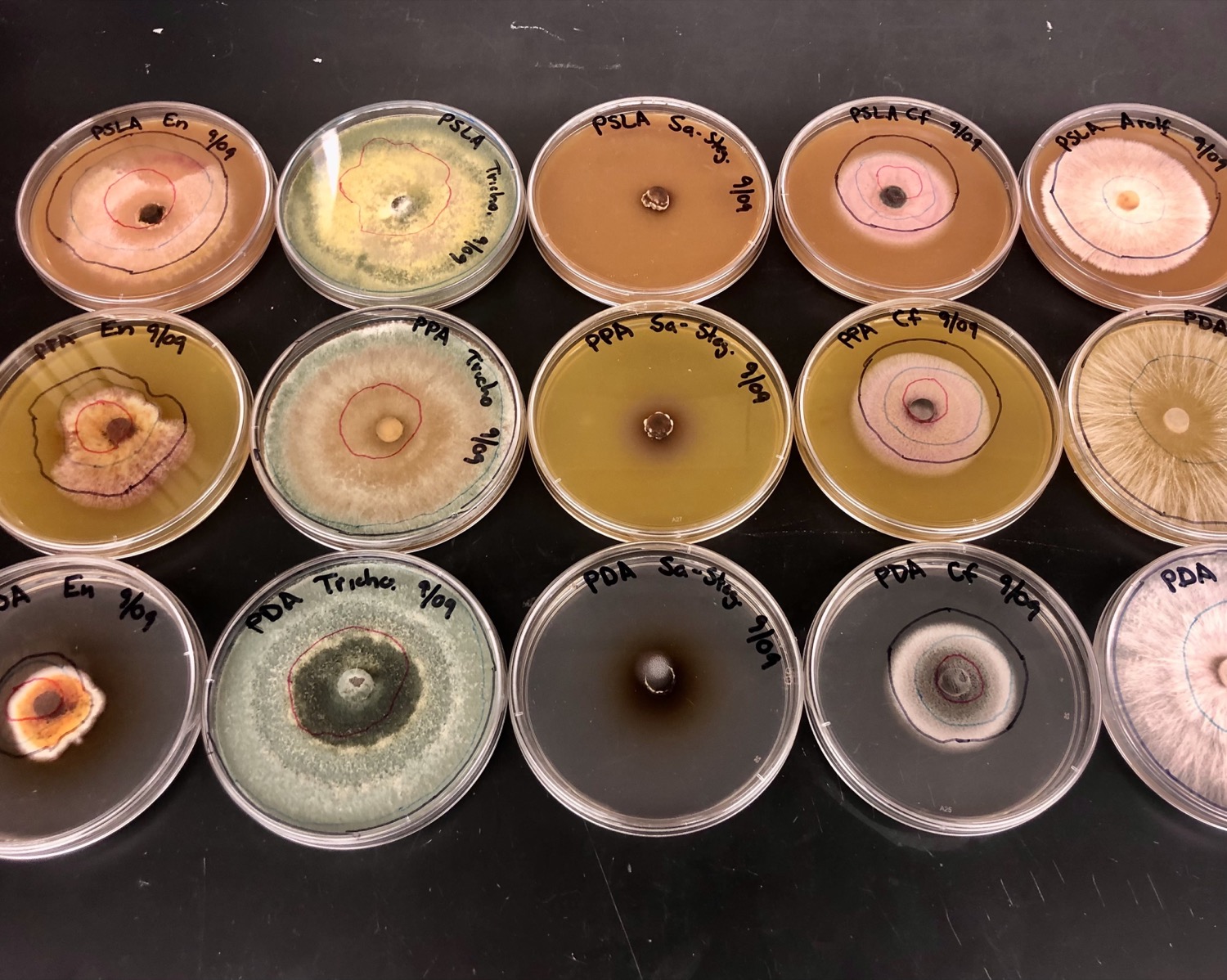

Kasson plated the various fungi species, including Athelia rolfsii, on different combinations of pumpkin spices. He cooked up three types of pumpkin spice growth mediums, in addition to a control plate of potato dextrose media typically used for bacteria and fungi experiments. The pumpkin spice latte agar used the drink directly from Starbucks (which only started to include real pumpkin in 2015). While the exact recipe isn’t known, it includes a bit of coffee, steamed milk, spices, and potassium sorbate and other food industry preservatives, Kasson says. The second agar—which he called the pumpkin pie agar—more closely resembled an actual pumpkin treat, with Libby’s canned pumpkin and a few grams of pumpkin spice. Finally, he created a more minimal agar using only the spices. While boiling up the various pumpkin spice media it was like he had dessert on a hot plate, he says: “The lab smells glorious.”

The true test is whether the decomposers will enjoy the pumpkin, too. Fungi often act as “gatekeepers,” doing the initial legwork for bacteria and other organisms to follow afterwards, Kasson explains. These are complex foods for fungi, but some species have specialized chemical “toolkits” available to help break them down. For instance, certain fungi can change the pH or secrete enzymes to modify conditions to be more favorable for its own growth, he says. “So we can learn something about their different tools in their toolkit, essentially, by exposing them to really unique substrates or really extreme environments.”

It’s been almost a week since he first began the experiment and inoculated the fungi, so they still smell pleasant—for now. The scent can shift as the decay progresses, going from a lovely floral or fruity fragrance to rancid pepperoni in three days, Kasson says. The fungi have also been forming colorful spectacular shapes: puffy white cotton, crusty green mats, orange carpets, brown spikes and appendages. There have been some species that haven’t been growing on the plates just yet, he says, but they are changing the color of the media.

“Often that’s a sign that the fungus is trying to modulate or change the environment before it grows,” Kasson explains. Variable growth rate between species is normal, and Kasson suspects that those plates might see growth soon.

So far, most of the fungi species seem to be faring poorly on the minimal pumpkin spice agar, which is likely due to the limited amount of nutrients needed for growth, he says. Though some of the generalist fungi, such as species of Trichoderma and Coprinellus, do show signs of slow growth on these plates—hinting that these fungi can tolerate a poor nutrient environment or heavy spice load.

[Related: Why autumn air smells so delicious and sweet]

He did notice a surprising pattern: Most of the fungi species grew better on the media made with the Starbucks pumpkin spice latte. But A. rolfsii—the southern blight pathogen—did better on the pumpkin pie media compared to the pumpkin spice latte. The growth patterns could mean that some of the ingredients in PSL could be problematic for fungi like A. rolfsii. It also suggests that the species preferred to grow on the substrate it was found consuming in the wild.

“What’s clear about a pumpkin-loving fungus like A. rolfsii is that it knows the real thing when it tastes it,” says Kasson. “So retailers beware, our fungus can decipher your secret recipe, pumpkin or not.”

Check out more images from Kasson’s #WholeLatteDecay outreach project below. All images and caption information courtesy of Matt Kasson.