A molecule-mapping method developed by IBM researchers has unveiled the structure of a deep-sea compound, and the process could lead to faster drug development, according to a new study.

Using atomic force microscopy, researchers in Scotland and Switzerland were able to see the molecular structure of a marine compound recovered from the Mariana Trench, whose chemical composition was unknown. And it took only a week to figure it out.

Previously, molecular imaging has relied on indirect methods like X-ray crystallography, which bounces X-rays off a molecule, or nuclear magnetic resonance imaging, which examines how the atoms of a molecule absorb radio waves. But the new technique is akin to taking a snapshot or blueprint of the molecule.

Ultimately, the scientists realized they were looking at a compound that had already been isolated from a Taiwanese orchid.

Chemical compounds from the ocean could lead to new drug therapies — painkillers synthesized from sea-snail spit, for instance. But researchers have to find new chemical compounds first, and then they have to understand what they’re looking at.

In the new study, reported in Nature Chemistry, researchers at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland examined a bacterium taken from a Mariana Trench mud sample. The bacterium, Dermacoccus abyssi, is pressure-tolerant enough to live at 35,814 feet beneath the sea surface, and it produces a chemical compound that the scientists couldn’t recognize.

They used high-resolution mass spectrometry to figure out what was in the compound, but they still could not figure out its structure. The only choice would be to take a chemical synthesis of the proposed structures, but that is complicated and can take several months. That’s where IBM stepped in.

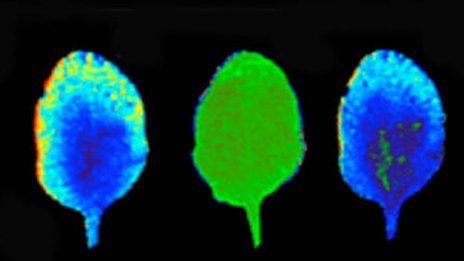

IBM scientists used a technique called noncontact atomic force microscopy to take images of individual molecules at the atomic scale. Along with some density calculations, they determined the strange chemical was actually cephalandole A, which is already a candidate for new types of drugs, Nature News reports.

Leo Gross, who led the IBM research team in Zurich, says his technique can speed up the process of identifying exotic chemical compounds from Earth’s extreme regions.

Last year, Gross’ team showed they could make highly sensitive AFM instruments that can take close-ups of a small organic molecule for the first time.

Nature News points out that the technique is not perfect — some scientists wonder if the measuring method itself, which involves placing the molecule on a salt crystal, might interrupt the molecule’s structure. If you don’t know the shape to begin with, you can’t know whether the salt affects the shape.

But combined with indirect methods, it could help researchers quickly identify new compounds, which could speed up the process of producing new drugs, IBM says.