There’s a lot of misinformation blowing around out there concerning the medical benefits, and detriments, of smoking marijuana, but two UK researchers are making an argument for why you should perhaps pass on the puff-puff — as well as why recreational use should not be outlawed in the future.

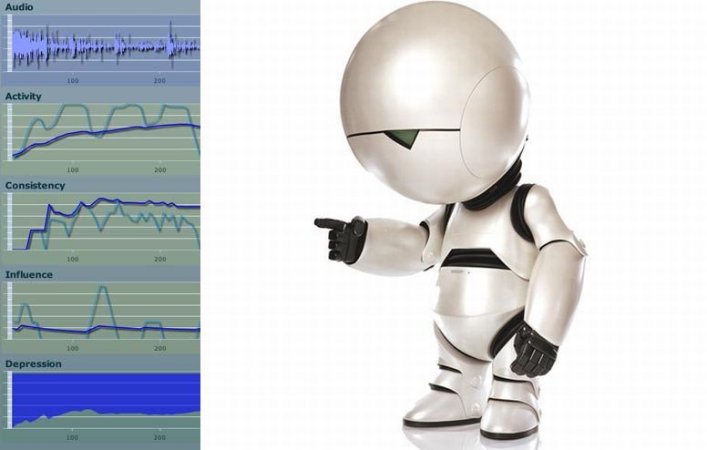

Cannabis has been shown through research to spur the brains of a susceptible minority toward long-term psychosis, particularly in young people who can significantly increase their risk of developing a disorder like schizophrenia. Findings like these often get a good deal of play in the media, not always accompanied by the key phrase “susceptible minority,” fueling the Reefer Madness-like obsession with banning pot outright.

Amanda Feilding at Oxford’s Beckley Foundation and Paul Morrison at London’s Institute of Psychiatry argue that what’s often overlooked is the kind of pot consumed, and that requires a more Mendelian approach to the problem. Your parents may have told you that the grass in their day wasn’t as strong, while the old guy that hangs outside the grocery may hold the opinion that you just can’t get the good stuff anymore. They could both be right. The problem is one of balance.

Street cannabis — aka “skunk” — has been selectively bred to increase the level of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). That’s not news. But Feilding and Morrison point out that, in upping the potency through selective breeding, another important molecule, cannabidiol (CBD), has been selectively eliminated from skunk over time.

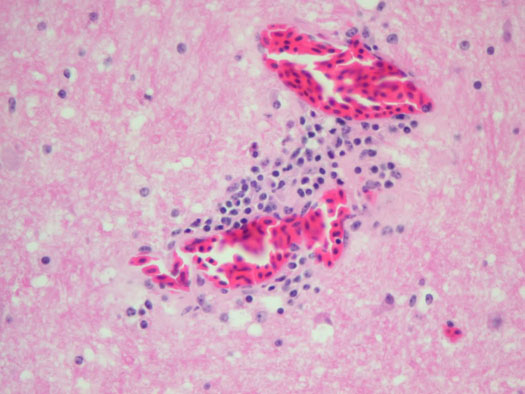

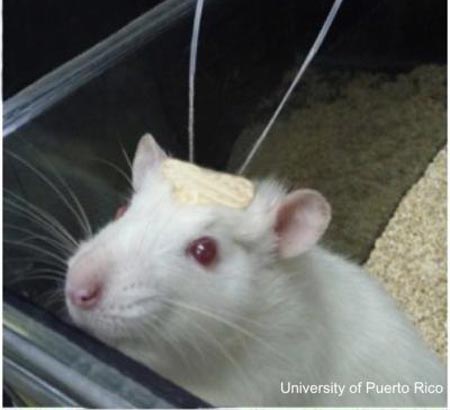

Research on CBD shows it to have an antipsychotic effect, the yang to THC’s yin. So the selective breeding to make pot more potent has also made it more dangerous, throwing the psychotic/anti-psychotic balance strongly in favor of the psychotic. To boot, Feilding, Morrison, et al. have run some experiments administering THC and CBD to volunteers that bolster these claims, and they’re setting up further research projects at dispensaries in California to further test their hypothesis, that pot bred to be high in THC but also in CBD would not have the harmful psychosis-aggravating effect of modern skunk.

The implications here, of course, are vast. First, Feilding and Morrison’s work makes a strong case for the regulation of recreational pot market; as long as marijuana remains a black market good, growers will strive for a more potent product over a safe one, and if the psychosis issue is removed from the argument there’s really little reason to keep pot illegal. But it also raises questions about the future of drugs, both legal and illegal. Can a Peruvian coca farmer selectively breed coca that is easier on the brain? Could opium farmers intelligently develop a pharmaceutical class of less-addictive opiates through unnatural selection? Can we employ Darwinian principles to bring illegal drugs safely back into the legal mainstream? It’s enough to blow your mind.