Hop in an airplane today, and it will get the thrust it needs to fly through the air either from a propeller or a jet engine. Both methods require moving parts—a propeller spins, and a jet engine has a fan inside. And as such, they are loud. That’s been status quo since Kitty Hawk.

But now aeronautics experts at MIT have flown a radically different type of plane that is thrust through the air using just electricity and the movement of ions, a type of silent drive without moving parts out of science fiction.

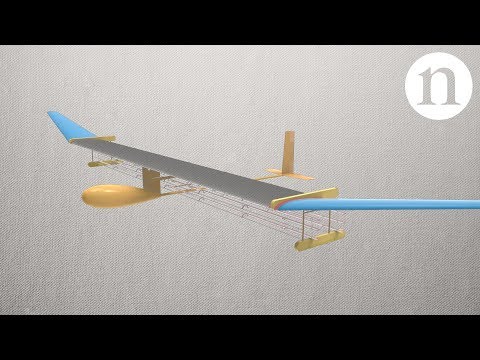

The researchers flew the airplane a total of ten times at an indoor track at MIT. It weighs a little over 5 pounds, has a wingspan of about 16 feet, and flew about 230 feet on its longest flight—roughly the twice the wingspan of a Boeing 737—before smacking into the gym’s wall. Its speed is about 11 mph. The tech powering the plane is called electro-aerodynamic propulsion.

“What we achieved was the first ever sustained flight of an airplane that is propelled by electro-aerodynamic propulsion, and that’s also, by many definitions, the first ever solid-state flight, meaning no moving parts,” Steven Barrett, a professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT, said in a video about the plane.

Here’s how the tech works—which could someday be used to create drones, or even bigger craft, with solid-state propulsion systems.

The key components are electrodes under the wing that run horizontally. There are many of them, but to understand how the airplane flies, you only need to consider the relationship between two. One electrode is thin, like a wire, and thanks to a battery and power converter onboard the plane, that electrode is charged to a whopping 20,000 volts of electricity. Behind that thin electrode, and more towards the back of the plane, is another one—it looks like a tiny wing. That second electrode is charged with negative 20,000 volts, creating a difference of 40,000 volts.

Just like you wouldn’t want to touch a propeller, you shouldn’t reach for these electrodes, either. “It could be pretty dangerous,” says Barrett, who is also the senior author on a new study in the journal Nature describing the aircraft. “We’re talking quite a lot of power.”

Those two electrodes can help make the plane fly because the first one, charged to 20,000 volts, spurs nearby nitrogen molecules to lose an electron and become positively charged. The positive nitrogen ions are then attracted to the second electrode, which has a negative charge. The magic happens while a nitrogen ion is traveling between the electrodes, because it bumps into regular air molecules. “And on each collision it transfers energies to those molecules, and creates a wind of neutral air,” Barrett says. Presto: an airplane powered by ions.

If you’re wondering what happens to the sad nitrogen molecules that lose an electron when they hit the first electrode, don’t worry: they regain them once they hit the second one, becoming neutral again. “And then it continues on its way as though it had never been involved in the process in the first place,” Barrett says.

In the future, Barrett says they’d like to take those electrodes and bake them into the skin of a next-gen aircraft, so there would be no need for the external ones on this prototype. Not only that, he says that the ion drive could even be used to steer the plane going forward, so it wouldn’t need traditional control surfaces, like a rudder or elevator, which is the part of the smaller wing at the back of a plane that control’s a craft’s pitch. That way the solid-state engines would not only propel the plane, it would control its direction.

It’s early days for this technology, though. The Nature paper points out that designs like this one are “not yet competitive against conventional aeroplanes at similar scale in metrics such as range, endurance, and payload capacity.”

Still, Barrett says the ion drive could power miniature drones, or other craft built on the same general scale as the prototype they already flew. “I do hope that we can develop this towards larger aircraft that maybe even eventually could carry passengers,” he says.