From cities in the sky to robot butlers, futuristic visions fill the history of PopSci. In the Are we there yet? column we check in on progress towards our most ambitious promises. Read more from the series here.

Nothing captures the human imagination quite like the thrill of flying. Not the middle-seat-on-a-plane kind of flying, pressed between the lucky passengers who scored the window and aisle seats, passive-aggressively vying for elbow space, while watching with resignation as an airplane icon creeps toward its destination on a crude digital GPS map plastered to the seatback in front. But rather, the kind of flying that would enable us to break free of gravity’s yoke and the roads that hem us in—soaring solo into the third dimension with air rushing over our limbs. This kind of unfettered flight inspired Hugo Gernsback’s August 1928 cover of the iconic science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, with fictional spaceman hero Buck Rogers sporting a backpack that boosted him into the air. Inventors have been chasing these kinds of lightweight jetpacks ever since.

“The appeal of the jetpack is that it’s something you can stow in a locker, pull out, and put on to go somewhere,” says John Hansman, a professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT. “But the versions we’ve seen so far don’t make a lot of sense. They are just stunts.” Despite the array of fantastical, but perhaps impractical (and dangerous) jetpack designs, Hansman adds, “It’s an interesting time. There are a number of technologies coming online that could give you the capability of a jetpack.”

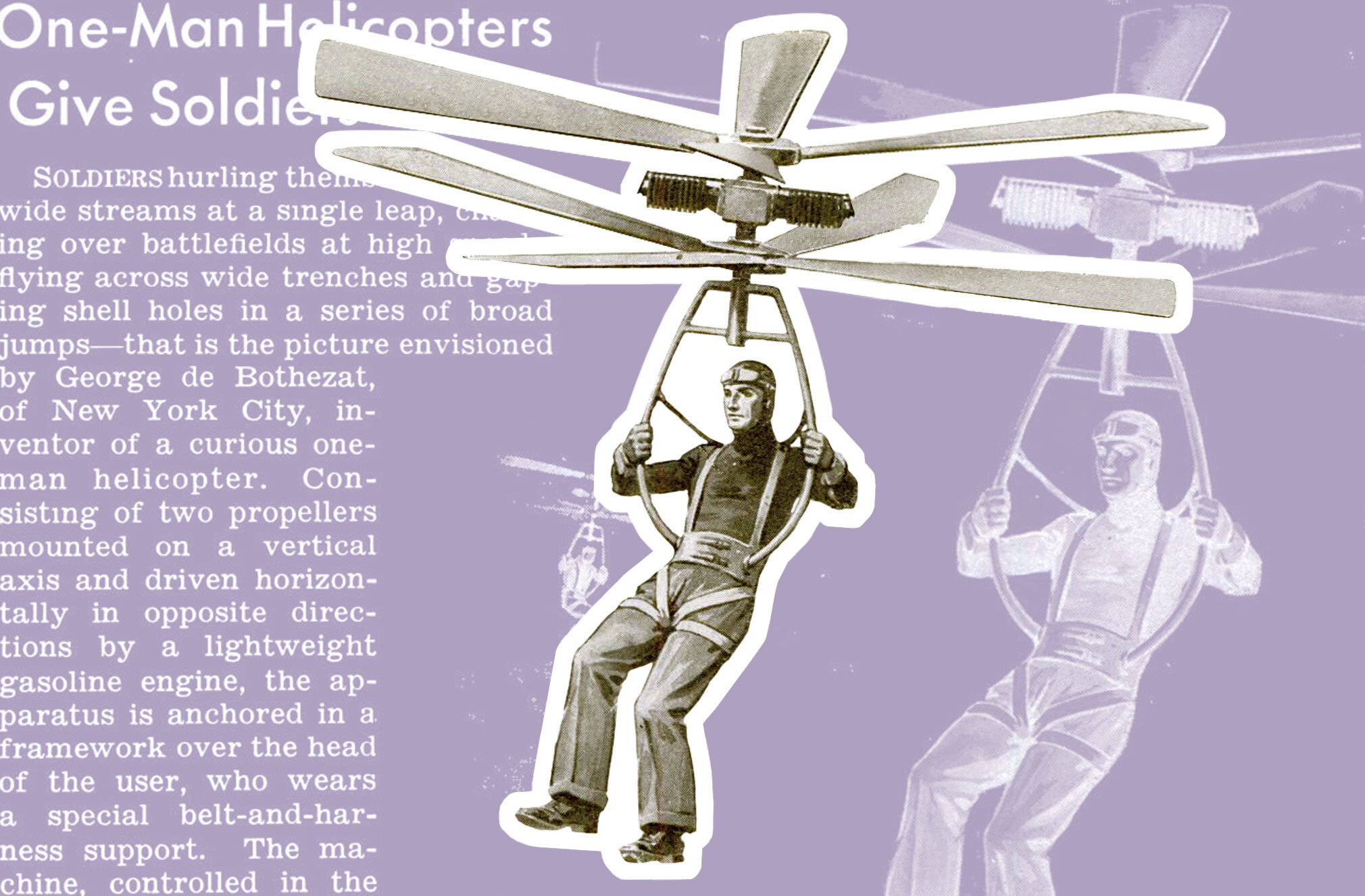

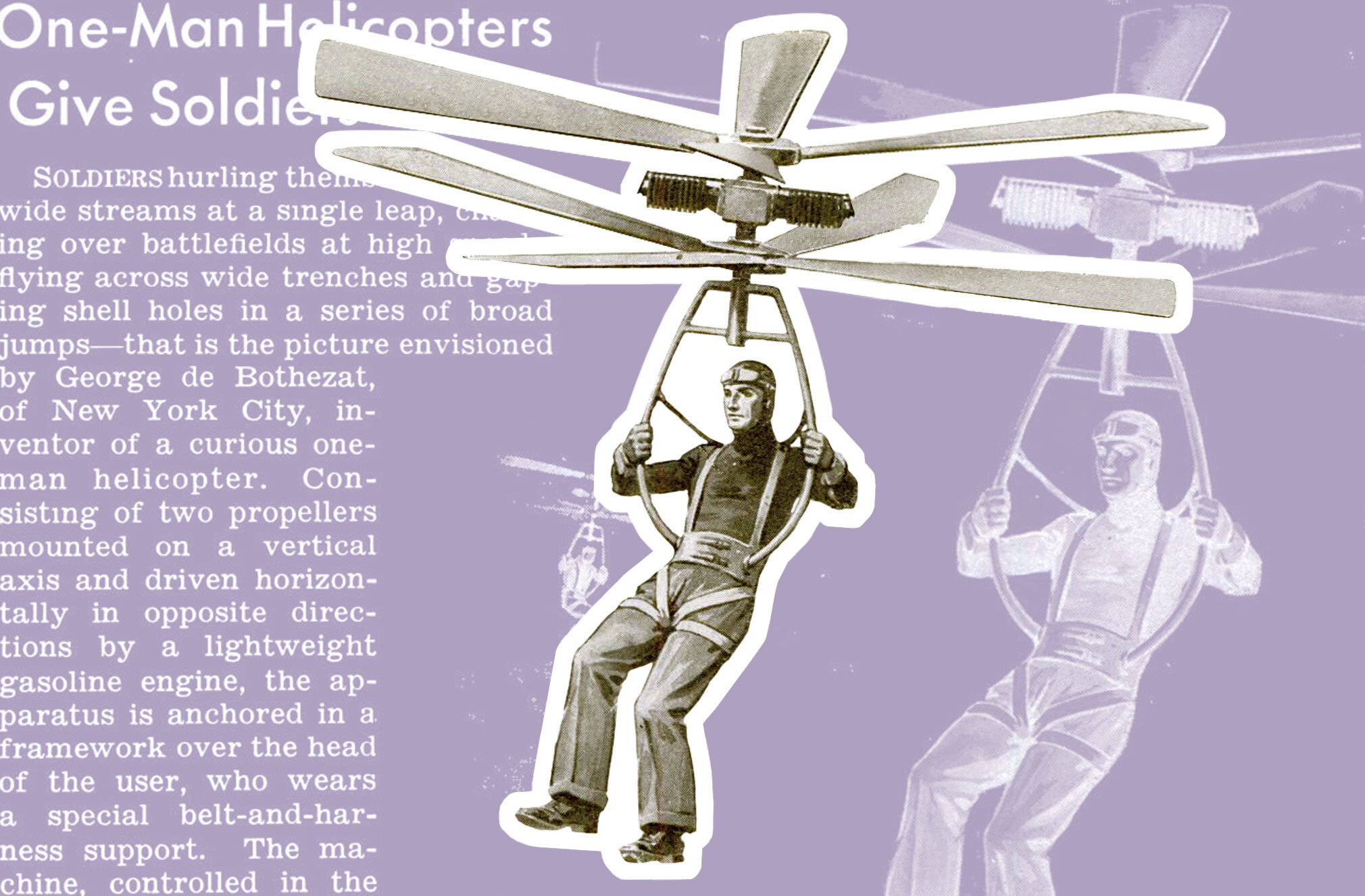

For more than eight decades, Popular Science has been chronicling the effort to get jetpacks off the ground. Our first story was published in March 1940 with Russian-born inventor George de Bothezat’s one-person helicopter—a simple frame with twin props spinning overhead, powered by “a lightweight gasoline engine.” The apparatus was controlled in the air by the pilot’s body, arm, and leg movements. De Bothezat died before he could actually build the invention. But his attempt was not entirely for the birds. In July 1945, we described the efforts of Boeing engineer Horace T. Pentecost, who improved upon de Bothezat’s design with a “flight stick” for steering. Pentecost rebranded the whirligig a “hoppicopter”—the gizmo only capable of staying in the air for short distances.

Popular Science began taking slow-to-evolve jetpacks more seriously in January 1952 when two pages of the magazine were devoted to the next generation of Pentecost’s hoppicopter: Gilbert Magill’s pinwheel. Magill kept the overhead rotors from the original design but upgraded the stick and added a seat and pilot safety gear (whew)—little more than a “crash helmet with a plastic face shield.”

The first jet engine-like breakthrough arrived in our December 1958 feature, which described the US military initiative “Project Grasshopper” that sought to upgrade a secret jump rocket into a flying belt. Jump rockets were a “solid-fuel device” that could be strapped around a soldier’s waist to enable them to jump distances as wide as a 50-foot river or leap up into a second-story window. Project Grasshopper’s goal was to extend the jumper’s air time using nitrogen-compressed gas canisters that could be “snapped in place of exhausted ones in less than a minute.”

Soon after, Bell Aerosystems’ engineer Wendell Moore made a big jetpack leap with the Rocket Belt (also funded by the US Army), a personal propulsion device spotlighted in a January 1966 rundown of James Bond gadgetry. Sean Connery strapped into Bell’s Rocket Belt for the opening escape scene in the 1965 Bond film Thunderball, rocketing away Buck Rogers-style from a villain’s chateau. The name Rocket Belt came from the rocket engine propulsion design. The engines run on distilled hydrogen peroxide and nitrogen gas, which is used to generate high-pressure, super-heated steam that thrusts the pilot skyward. Other designs of rocket belts have shown some staying power, at least for big-event stunts like the opening ceremony of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. We covered them as recently as March 2006, in a profile of homemade rocket-belt builder Juan Lozano. Even in 2006 we remained skeptical about their ability to bestow true jetpack-flight freedom, PopSci staff awarding Lozano’s rocket belt a reality meter score of 2 out of 10, meaning the chance of a commercial breakthrough was slim.

While momentum seemed to be rising with the rocket belt, jetpack development suddenly fell flat. Besides covering the occasional space-based jetpack (November 1971), there weren’t many new developments to report. Then in December 2008, New Zealand inventor Glenn Martin’s decades-long quest to build a ducted fan (non-jet), gasoline-powered jetpack paid off. Ducted fans rely on rotary-style propellers contained in a canister to direct thrust. Martin’s jetpack was so noteworthy that he earned a spot in the magazine’s coveted list of top innovators.

A couple months later in February 2009, we covered the strange story of Swiss pilot Yves Rossy, or Wingman, who had attached mini-jet engines to a homemade wing, strapped himself in, and jumped out of a plane over the English Channel. While technically not a jetpack, Rossy’s wing did use a true jet engine, foreshadowing what was on the horizon.

By the 2010s, jetpacks and other personal aircraft innovation reached a new height—hoverboards, flyboards, and water-powered jetpacks, not to mention countless drones, had taken over. Then, after a seven decade journey from the solo-operated helicopter of the 1940s to the ducted fan of the 2000s, a true jet-engine jetpack finally emerged with a form factor and lift that would have raised Buck Rogers’s eyebrows. JetPack Aviation conducted the maiden flight of its wearable launcher around the Statue of Liberty in New York on November 3, 2015. All the while, New Zealand inventor Glenn Martin, continued to improve upon the ducted fan jetpack, finally attracting the kind of venture capital to expand his company Martin Jetpack and offer a consumer product.

By 2017, the promise of solo flight seemed so real—and potentially profitable—that Boeing sponsored a $2 million competition GoFly to encourage personal aircraft innovation that would bring them into the mainstream. The aerospace company saw promise in the growing progress in the technology, such as improvements in propulsion, light-weight materials, and control and stability systems.

In 2019, before the GoFly finals had concluded, we took another look at the jetpack reality meter and decided that, while progress had been made, the tech was still too noisy, too heavy, and too expensive. The GoFly judges seemed to agree because, while they doled out some awards for innovation, no one won the contest. None of the entrants met the contest’s basic size constraints and flying-time parameters, among others. John Hansman, who had been an initial advisor but dropped out, wasn’t surprised by the disappointing outcome.

According to Hansman, there are way too many things that can go wrong with a Buck Rogers-style jetpack. He calls it an extreme version of a motorcycle, but even more dangerous because of altitude and speed. Plus, jet engines are not the most effective way to get around Earth. “Jetpacks work great in space,” Hansman notes, “where the best way to get propulsion is to push a gas.” Where there’s an atmosphere, however, “a jet engine doesn’t compete very well with a rotor propeller.” Jetpacks require continuous thrust to stay aloft—therefore expending a lot of fuel—whereas propellers leverage Bernoulli’s principle, or the difference in air pressure above and below the rotor.

But jetpack designers today are learning from decades of trial and error. Hansman believes the field is on the cusp of a fresh round of innovation in personal aircraft, but not in the classic jet-engine backpack form. “Nothing has changed substantially on the jet side,” notes Hansman—there hasn’t been enough development to convince him that jet engines offer the best design. Rather, he sees personal aircraft in the form of rotor-based airbikes or hoverboards. “If you think about the technologies that have come along,” he says, “it’s battery technology in electric aircraft, distributed propulsion, and relatively inexpensive active control systems.” Drones, for instance, can have cheap active control systems that use sensors and software to stabilize them. Distributed propulsion, where there are multiple rotors working in coordination, has enabled the design of crafts like hoverboards and, perhaps in the near future, air taxis and air bikes.

Hansman sees the market initially embracing recreational personal aircraft, similar to jet skis on the water. That’s because building a reliable, commuter-style vehicle requires a different level of engineering to handle the wear and tear of daily use. Plus, there’s the matter of navigating controlled airspace. Even though the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) does not regulate ultralight aircraft (single person, less than 254 pounds empty, and with max speeds no more than 60 mph), or direct traffic in airspace below 400 feet, they do restrict airspace around airports and cities. Those restrictions will have to be modified to realistically support personal commuter aircraft.

Despite the remaining obstacles, jetpacks and other personal aircraft have come a long way and are closer to reality than they’ve ever been. For hardcore jetpack enthusiasts, there are a number of companies like JetPack Aviation, Martin Jetpack, Gravity Industries, and Maverick Aviation that have working products—that is, if you have cash to burn and you aren’t intimidated by the danger of these devices. For those seeking safer ways to experience the thrill of solo flight, it may not be long before a weekend excursion to the mountains comes with an airbike or hoverboard rental that will allow you to soar over treetops and lakes, 20 minutes at a time. But if your goal is to sweep past traffic-snarled streets and highways on your daily commute, gloating at earthbound motorists as you glide overhead, you’ll have to wait even longer—and unfortunately what you’re waiting for will likely not be found in the Buck Rogers aisle of a future flymart superstore.