From concerns over blue light to digital strain and dryness, headlines today often worry how smartphones and computer screens might be affecting the health of our eyes. But while the technology may be new, this concern certainly isn’t. Since Victorian times people have been concerned about how new innovations might damage eyesight.

In the 1800s, the rise of mass print was both blamed for an increase in eye problems and was responsible for dramatizing the fallibility of vision too. As the number of known eye problems increased, the Victorians predicted that without appropriate care and attention Britain’s population would become blind. In 1884, an article in The Morning Post newspaper proposed that:

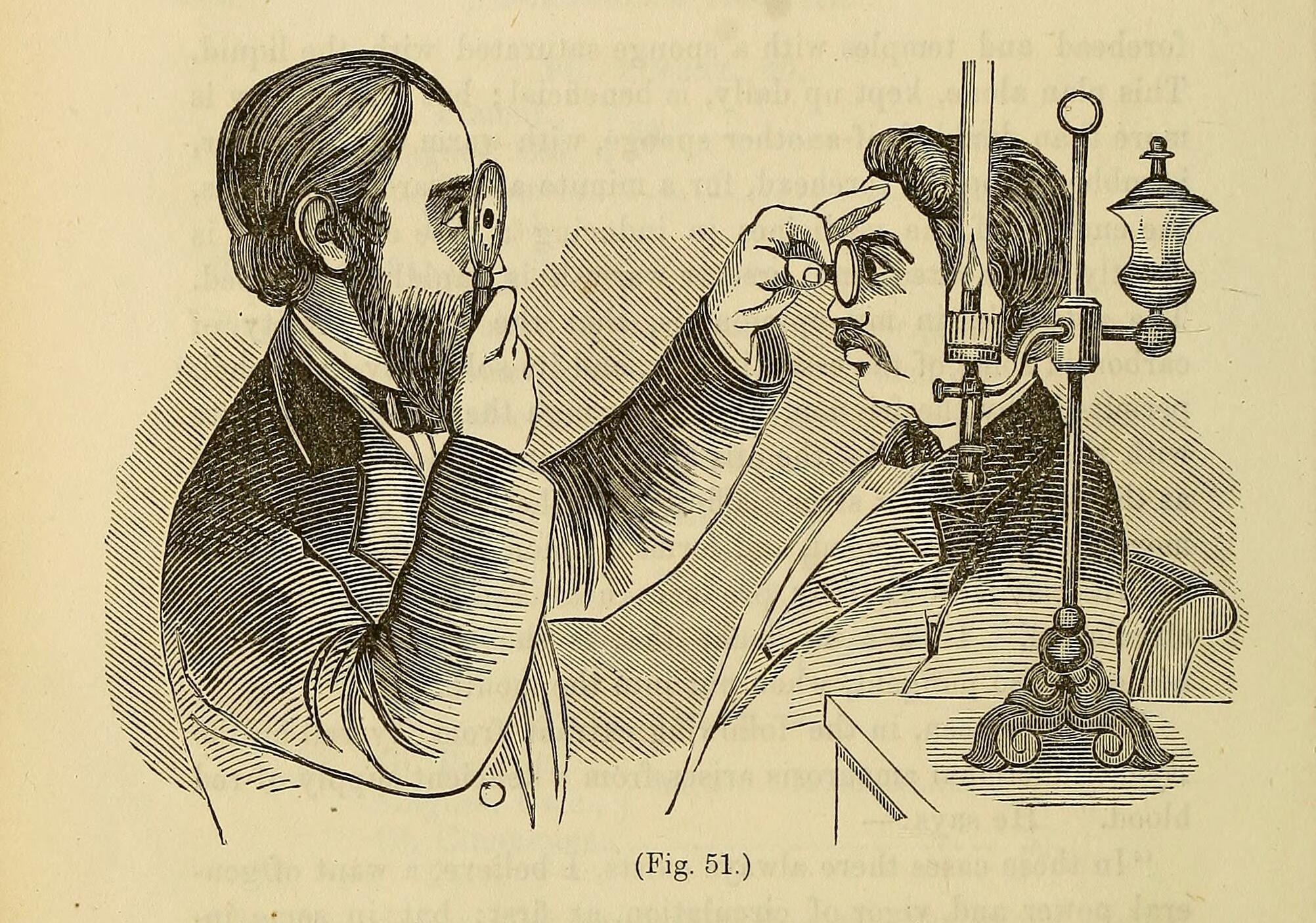

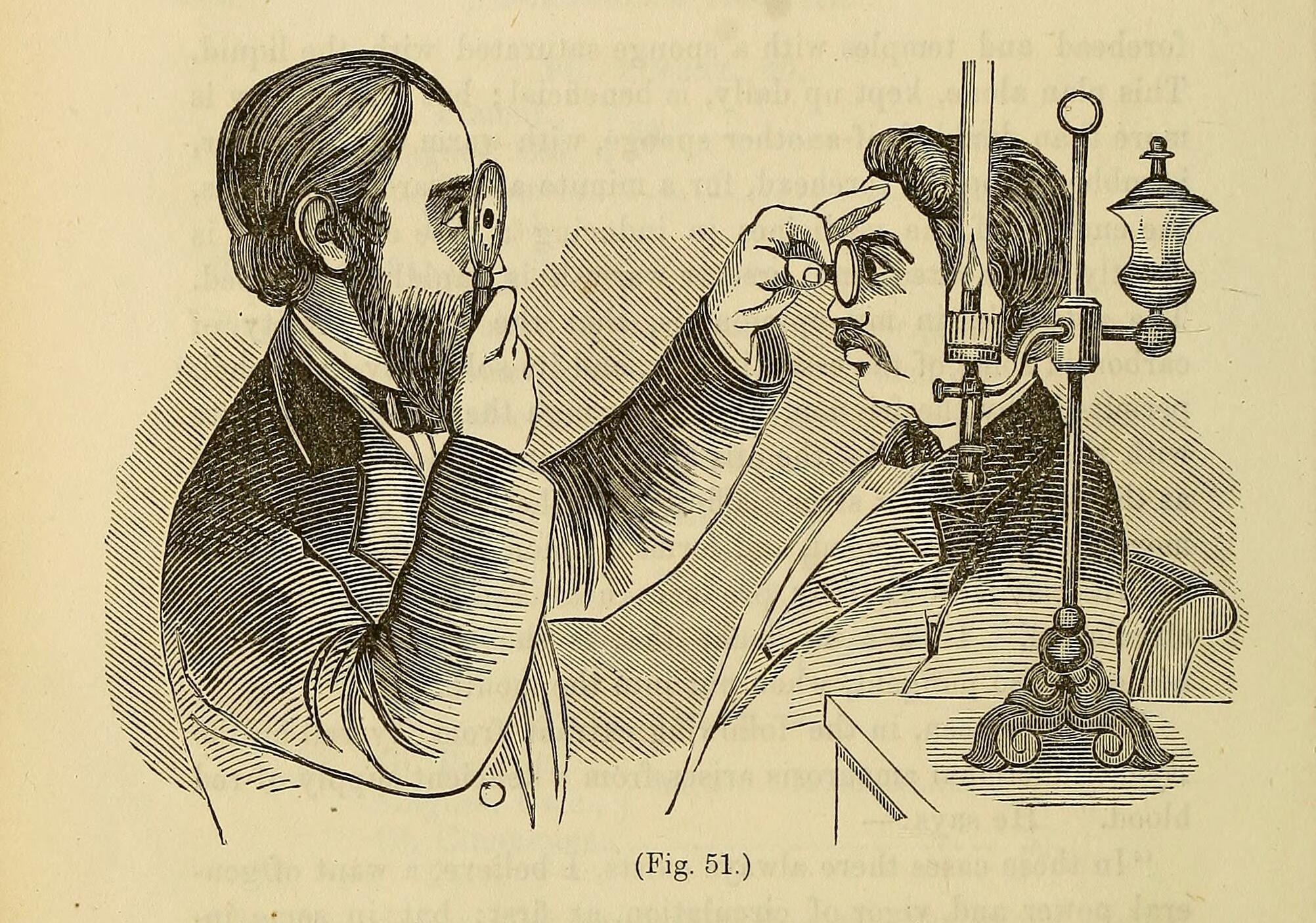

The 19th century was the time when opthamology became a more prominent field of healthcare. New diagnostic technologies, such as test charts were introduced and spectacles became a more viable treatment method for a range of vision errors. But though more sight problems were being treated effectively, this very increase created alarm, and a subsequent perceived need to curtail any growth.

In 1889 the Illustrated London News questioned:

The article continued, considering potential causes for this acceleration, and concluded that it could be partly explained by evolution and inheritance.

Urban myopia

Other commentators looked to “modern life” for explanation, and attributed the so-called “deterioration of vision” to the built environment, the rise of print, compulsory education, and a range of new innovations such as steam power. In 1892, an article, published in The Nineteenth Century: A Monthly Review, reflected that the changing space of Victorian towns and lighting conditions were an “inestimable benefit” that needed to be set against a “decidedly lower sight average.” Similarly, a number of other newspapers reported on this phenomenon, headlining it as “urban myopia.”

In 1898, a feature published in The Scottish Review—ironically entitled “The Vaunts of Modern Progress”—proposed that defective eyesight was “exclusively the consequence of the present conditions of civilized life.” It highlighted that many advances being discussed in the context of “progress”—including material prosperity, expansion of industry, and the rise of commerce—had a detrimental effect on the body’s nervous system and visual health.

Another concern of the time—sedentariness—was also linked to the rise in eye problems. Better transport links and new leisure activities that required the person to be seated meant people had more time to read. Work changed as well, with lower-class jobs moving away from manual labor and the written word thought to have superseded the spoken one. While we now focus on “screen time,” newspapers and periodicals emphasized the negative effects of a “reading age” (the spread of the book and popular print).

Education to blame

In a similar manner to today, schools were blamed for the problem too. Reading materials, lighting conditions, desk space, and the advent of compulsory education were all linked to the rise in diagnosed conditions. English ophthalmologist Robert Brudenell Carter, in his government-led study, Eyesight in Schools, reached the balanced conclusion that while schooling conditions may be a problem, more statistics were required to fully assess the situation. Though Carter did not wish to “play the part of an alarmist,” a number of periodicals dramatized their coverage with phrases such as “The Evils of Our School System.”

Related: Is my headache actually eye strain?

The problem with all of these new environmental conditions was that they were considered “artificial.” To emphasize this point, medical men frequently compared their findings of poor eye health against the superior vision of “savages” and the effect of captivity on the vision of animals. This, in turn, gave a more negative interpretation of the relationship between civilization and “progress,” and conclusions were used to support the idea that deteriorating vision was an accompaniment of the urban environment and modern leisure pursuits—specific characteristics of the Western world.

And yet the Victorians were undeterred and continued with the very modern progress that they blamed for eyesight problems. Instead, new protective eyewear was developed that sought to protect the eye from dust and flying particles, as well as from the bright lights at seaside resorts, and artificial lighting in the home.

Despite their fears, the country did not become “purblind.” Neither is Britain now an “island full of round-backed, blear-eyed book worms” as predicted. While stories reported today tend to rely on more rigorous research when it comes to screen time and eye health, it just goes to show that “modernity” has long been a cause for concern.

Gemma Almond is a PhD Researcher at Swansea University. This article was originally featured on The Conversation.