Click here to see all of PopSci’s COVID-19 coverage.

The number of new coronavirus cases in the US is on the rise again, with a few hotspot states contributing to most new infections.The Delta variant continues to gain ground globally, and studies suggest available vaccines have variable efficacy rates against it. Additional doses of vaccines may be a useful tool for boosting immunity in immunocompromised individuals. And birthday parties may be riskier than grocery shopping, according to new research.

Here’s what unfolded over the past week.

U.S. cases are slowly creeping upward again

Nationwide new COVID cases are up 5 percent over the last two weeks, thanks to rising cases in 16 states and Washington D.C., according to the New York Times. Nine out of 10 states with the highest per capita infection rates have vaccination levels below the national average of 47 percent full vaccination. Arkansas and Missouri are experiencing the most daily new cases per 100,000 people, at 17 and 16 respectively. In both states less than 40 percent of all residents are fully vaccinated.

The rise in cases is likely largely attributable to variable vaccination rates and the highly infectious Delta variant, now present across the US and accounting for more than 80 percent of new infections in Arkansas, Missouri, Connecticut, and Kansas. And it’s possible that areas with both low vaccination rates and high Delta prevalence could set the stage for the emergence of future dangerous variants. “Delta plus” variants have already begun showing up in some regions. Yet each of these factors alone doesn’t always correspond with high local COVID case numbers, and there are regional exceptions to the trend.

For example, although the Delta variant is dominant in Connecticut, case counts continue to decline from already low levels. The state has one of the highest rates of full vaccination in the country, at 61 percent of all age groups. But Kansas, a state with low vaccination rates and high Delta prevalence continues to have a low per capita infection rate, even as numbers rise locally.

Many other variables like local mask mandates, state reporting practices, incomplete data, and chance also play a role in the numbers.

One particular place where COVID is currently spreading rapidly and likely to continue to spread is US border camps. The number of people being held in Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers has reached nearly pre-COVID levels, and few are vaccinated. More than 40 percent of all COVID cases reported in ICE facilities have occurred in the past few months, according to the New York Times. The spike echoes early pandemic trends of high infection rates and mortality among people in prisons and jails.

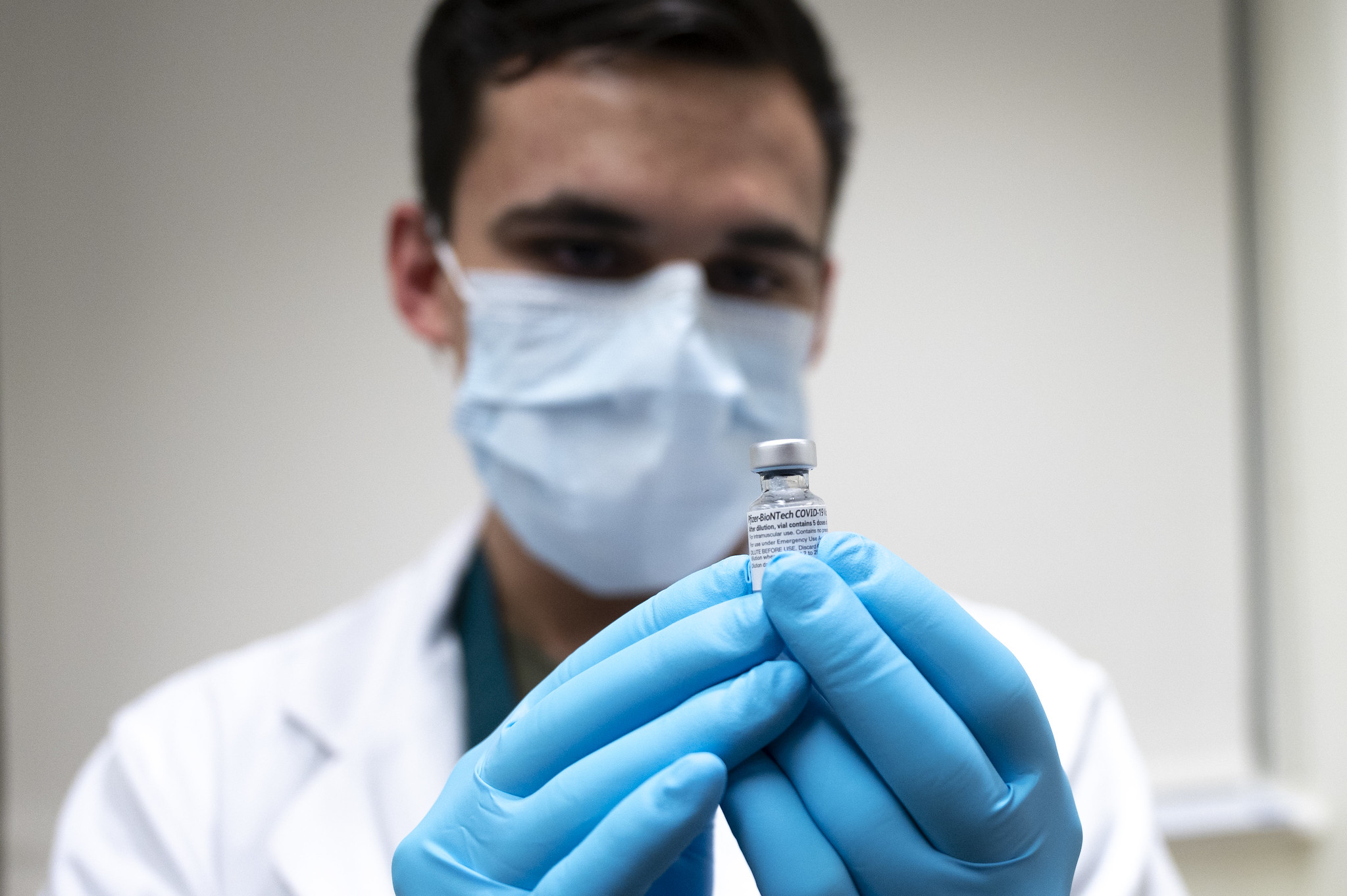

Pfizer vaccine may be less effective against Delta variant than originally reported, but is still very protective

Israel released data this week suggesting that the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine is just 64 percent preventative against Delta variant cases, but still highly effective against severe disease. The same data set showed the vaccine to be 94 percent preventative against hospitalization. The numbers cover the time period from June 6 to July 2 and are in contrast to earlier data. Previous reporting from May 2 to June 5 suggested the two-shot Pfizer vaccine was up to 94 percent effective against infection and 98 percent effective against hospitalization.

[Related: The Delta variant is forcing parts of Australia back into lockdown]

Around 60 percent of Israel’s population have at least one shot of the vaccine, and the nation had previously seen a large decline in COVID cases corresponding with vaccination efforts. In response, Israel ended social distancing and masking requirements. Indoor masking has since been reinstated in response to the Delta spread and gradually rising daily case numbers.

Data from the UK, where the Delta variant is similarly dominant, suggests efficacy against infection for a single dose of the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine is somewhere between 55 to 70 percent, while a two-dose regimen has an estimated efficacy of 70 to 90 percent.

Studies also suggest the Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines both provide protection against Delta variant

Johnson & Johnson reported on July 1 that their single-shot vaccine protects against the Delta variant, better than it did against the Beta variant, first detected in South Africa. However, the vaccine was slightly less effective against Delta than the original virus.

The news was coupled with results from a second study, suggesting immunity from a single J&J shot may increase over time. According to the company, antibodies against coronavirus infection persisted in those given the vaccine, and the antibodies seemed even more effective against illness eight months on from the jab than one month post-vaccination.

Both studies were small and have yet to be published in scientific journals, although one has been accepted for publication and the other has been submitted. One study followed 20 participants 29 and 239 days post-first vaccine shot. Half of the volunteers received one dose, while half got either a second J&J vaccine or an mRNA shot. One participant who received only a single J&J dose tested positive for coronavirus during the study period.

Meanwhile, Moderna announced its two-dose vaccine demonstrates efficacy against all tested variants, including Delta, on June 29. The study tested antibody-containing serum from eight vaccinated participants against multiple variants. Results showed the Moderna shots were slightly less effective against Delta and some other variants than the original virus, but still protective nonetheless. The press release also referenced a possible Moderna booster candidate which combines the original mRNA vaccine with a new formula.

Booster shots should be considered for immunocompromised people, research suggests

In France, people with certain immune conditions have been routinely administered a third mRNA vaccine shot, four weeks following the second, since April. Researchers have reported shot No. 3 boosts antibodies from 40 to 68 percent in immunosuppressed organ transplant recipients.

One US study has demonstrated similar findings among 30 individuals. The research looked at organ transplant recipients who had sought out third vaccination shots independently. Antibodies went up after shot No. 3 in one-third of participants who had no antibodies and in all patients who had low antibody numbers after a second shot.

People who receive organ transplants are put on a regime of immune-suppressing drugs so that their bodies will be less likely to reject the donor organ. Although these medications are helpful for transplant success, they can make people much more vulnerable to infection. Many other health issues and medications can also cause reduced immune system function, including cancers, liver and kidney diseases, and commonly prescribed steroids. About 5 percent of the population is estimated to be immunocompromised, according to the New York Times.

Both Pfizer and Moderna are in the planning stages of trials testing booster shots in immunosuppressed people. Booster shots for the hepatitis B and flu vaccines are already common practice for immunocompromised people.

Study suggests COVID often spreads via family and friends, not strangers

Reliable data on small gatherings and COVID-19 spread has been difficult to come by because small get-togethers are hard to track. However, one study published June 21 used an inventive method to demonstrate that small social gatherings like birthday parties may be an important source of coronavirus infections.

The researchers looked at health insurance claim data from last year and compared reported COVID rates within the two weeks following a family member birthdate with rates following randomly selected dates. They found that recent family member birthdays boosted coronavirus infection risk by about one-third in areas with widespread transmission. However, the data doesn’t directly track who among the study population actually had a birthday party.

The research serves as a reminder that, especially for the unvaccinated, small social gatherings remain risky.