In the Southside of Chicago, Ali Rashad works with a group of men to rebuild the community they live in; environmentally, spiritually, and economically. As the manager of the Inner-City Muslim Action Network’s Green ReEntry Program, Rashad helps formerly incarcerated individuals find jobs that are rooted in sustainability.The program, which has been operating for the last seven years, aims to provide these Chicago residents economic opportunity by rehabbing and revitalizing homes in Chicago Lawn, a neighborhood on the city’s southwest side that has experienced decades of white-flight, segregation, and changing demographics.The Green ReEntry Initiative runs a fully accredited program that helps members become certified for HVAC installations, carpentry, and electrical work. But in each step, the program emphasizes the use of environmentally friendly products and processes—from disposing of debris during construction to installing tankless water heaters and high efficiency furnaces. The organization is actively expanding its green jobs as well. Soon, they may include a solar panel installation track, further reducing the group’s environmental impact.Green ReEntry’s approach is part of a larger network of environmental justice organizations across the nation.

Historically, low income and minority communities have been on the receiving end of pollution, toxic waste, and other environmental problems at rates much higher than middle-class white Americans. Many of these communities have also been on the discriminatory end of the criminal justice system, public school funding, and access to amenities like parks and grocery stores.“The whole spirit of organizations like ours,” says Green ReEntry’s Rashad, “is a spirit of wanting to right social wrongs.”Communities like Chicago Lawn have experienced first-hand environmental and social injustices for decades, but it wasn’t until 24 years ago that this idea of environmental justice came to be legally recognized. On February 11, 1994, President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 12898, which mandated that federal government agencies had to take into account principles of environmental justice in their work.“What the environmental justice movement has been able to do, and do well, is redefine what environmentalism is and what the environment is,” says Robert Bullard, a professor at Texas Southern University’s School of Public Affairs. “It takes environmentalism out of the neat little boxes,” he says.Whereas environmentalism is steeped in the language of wildlife, wetlands, and nature, Bullard explains, environmental justice adds the built environment to the list of places that should be protected: where we live, work, play, learn, and worship.Bullard has been at the forefront of the American environmental justice movement from its start; he witnessed Clinton signing the Executive Order. But the movement predates Clinton’s order by years— centuries, in fact. America’s history of environmental injustice is as long and storied as its history of environmental protection.

The men who founded the crown jewels of the country’s National Parks did so by forcibly removing Native Americans from their indigenous lands. Gifford Pinchot, who crystallized American conservationist thought in the 1900’s, was a known eugenicist. His ideals were closely linked to ensuring the viability of the natural world to sustain and entertain the “superior racial stock.” Nine years after John Muir founded the Sierra Club in 1892, he published a series of essays collected in a book called “Our National Parks,” an extended love letter to Yosemite. “The Indians are dead now… Arrows, bullets, scalping-knives, need no longer be feared; and all the wilderness is peacefully open,” he wrote in a 1901 essay. For most of our country’s history, most efforts to protect the environment were actually only meant to preserve it for a select few. And that often meant deliberately placing pollutants in the neighborhoods of marginalized Americans.

“Back in the [1970s], there were environmentalists who [still] said, no, what you’re talking about is a social issue,” says Bullard. “We don’t work on social issues. No, you’re talking about civil rights or human rights. We don’t work on that.”

Bullard work turned from academia to activism when his wife, attorney Linda McKeever, asked him to help her collect data for a class action lawsuit she had filed over the location of city owned-landfills in Houston. Every single one was located in a predominantly African American neighborhood, and causing health issues from the proximity to environmental toxins. The initial lawsuit was among the first to challenge environmental injustices on the basis of civil rights. Although the judge ultimately denied an injunction, Bullard continued working on issues of environmental justice—and the momentum behind it was building.

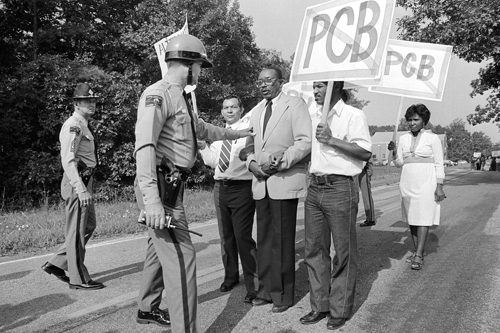

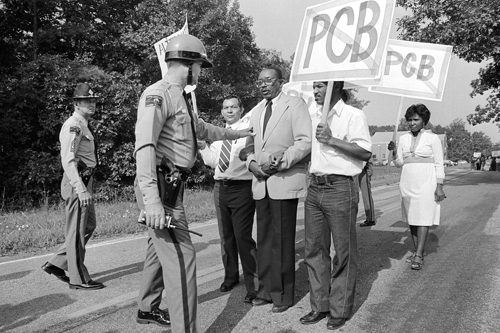

Thousands of miles away, a similar crisis made national headlines in Warren County, North Carolina in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The state government needed to build a landfill for the thousands of tons of contaminated soil that carried polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, a toxic industrial chemical that had been illegally dumped on roadsides. The North Carolina government decided to construct the landfill in one of the state’s poorest rural towns, in which three quarters of the population was African American.

PCBs are a known carcinogen that can cause a litany of health and developmental problems, particularly among children. PCBs also remain in the environment for a long time, meaning that contamination in soil, water, and air can last for decades. As such, they can often accumulate in the tissue of organisms—including humans—that encounter it. Community advocates wanted the landfill stopped, but in order to do so they had to prove beyond a doubt that the facility’s slated location had been racially motivated—a claim that state officials successfully denied in court.

The effort to compile and map the link between race and environmental hazards was monumental. At the time, no easily accessible databases from the EPA existed. That started to change after Ronald Reagan signed a law creating the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory (TR) in 1984. Spurred by gruesome industrial incidents like the nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island, and the gas leak at a Union Carbide chemical plant that killed more than 20,000 people in Bhopal, India and left generations exposed to toxins that caused birth defects, the law mandated that industrial facilities report information on chemical releases to the government and the public.

“The TRI database is something we take for granted today,” Bullard says. “Ordinary individuals can put in their zip code and address and identify what’s near schools and parks, what chemicals are released and stored. That information in the hands of ordinary people makes a lot of difference. That’s very empowering.”

Having data and technology readily available allows community members to actively engage and participate in every step of the civic process, from identifying problems to proposing solutions. Organizations like Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services in Houston, for example, monitor chemical leaks and spills in Houston’s industrial corridors with sophisticated equipment like thermal imaging cameras. This equipment detects toxic emissions that nearby residents of the predominantly Latino and African American neighborhoods might be breathing in, even if they can’t smell or see the substances. After Hurricane Harvey, TEJAS also partnered with researchers from Texas A&M University to record contanimation from floodwaters in environmental justice neighborhoods.

Last October, a local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, one of the country’s most prominent civil rights organizations, introduced a program to help middle school students in the heavily polluted and industrial Indiana town of East Chicago test their own water for lead contamination.

After seeing little progress from public officials, the Indiana NAACP decided to put the scientific tools in the hands of its own citizens. Some residents in the area lived in a housing complex that was literally built on top of a known lead refinery, according to local news reports. The complex is now an EPA Superfund site, although the contamination occurred decades before it was recognized as one.

The NAACP’s Environmental and Climate Justice Program was officially established in the late 2000s, but the organization has been engaged in advocating for clean water and clean air since the height of the civil rights era. “The association has been looking at these issues for a very long time, but it was largely framed as a public health issue,” says Marcus Franklin, the research and systems manager for the environmental program. In fact, the organization was one of many that sued the state of North Carolina on behalf of residents of Warren County.

At the national level, Franklin works on reports that are produced by the NAACP in partnership with scientific or environmental organizations, providing key data and analysis for local organizers. “One of the goals of our program is to bring the equity framework out there,” Franklin says. “We usually try to connect our units with universities and other organizations that can help facilitate data collection, and when we can, we advance projects that incorporate aspects of participatory science.”

Recently, the NAACP collaborated with the Clean Air Task Force on a report titled “Fumes Across the Fenceline”, documenting the high concentration of African Americans living near oil and natural gas facilities that release carcinogens like benzene and volatile organic compounds. African Americans were also 75 percent more likely to live in such communities than white Americans and as a result, had higher rates of cancer and asthma than the general population. That’s no coincidence: It’s a legacy of decades of segregationist housing policy as much as lax environmental regulations.

At the heart of it, pollution and environmental issues are an intensely local problem: families and communities are the front lines of exposure. It’s the same ethos that infuses the work of Green Re-Entry, in Chicago: community-based action is vital to lifting up neighborhoods that are glossed over when the focus rests squarely on national averages and indicators.

For West Harlem Environmental Action, or We Act, as it’s known, community-led civic engagement grounds the organization’s advocacy. “Yes, the big green groups have been creating environmental change for decades, with things like the Clean Water Act, and the Clean Air Act,” says Peggy Sheppard, the executive director of We Act. “But we are concerned with what’s happening in our neighborhoods. Not just that national air quality is better, but that air quality is better in all of our neighborhoods. In many respects, that’s harder work.”

In the early 2000’s, We Act filed a civil rights complaint against New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority for siting several bus depots in Harlem and Washington Heights, causing air pollution to increase in those neighborhoods because of the number of diesel vehicles that were crossing through them, including right in front of schools and parks in low-income neighborhoods. The group’s grassroots campaign helped influence the city to begin switching or retrofitting its fleet to hybrid engines with more filters for particulate matter that would, in effect, reduce this air pollution. “[Local] elected officials live in these neighborhoods,” Shepard says. “But they never thought about requiring that buses be cleaner— their priority is jobs. If they’re not pushed to think about it, and understand the impact, they’re not working on it.”

That’s why, advocates say, knocking on doors and bringing residents to the table is crucial to environmental justice. “You work with the people who are most affected, who are living closest to those problems, so that people can speak to the issues, and talk to their elected officials. They can go to Albany or Washington, and be a strong voice for the conditions they are experiencing.”

More recently, as part of its healthy homes campaign, We Act has focused on the impacts of indoor air pollution, which is a major cause of asthma and other illnesses. It took two years of organizing to build a city-wide coalition and pass the Asthma Free Housing Act which mandates that landlords conduct annual inspections for mold, pests and other allergens. “Air quality, chemicals—it affects pregnant women and children intergenerationally,” says Shepard. “You have to look at transit that is not spewing pollution, at the quality of food, and open spaces for recreation. All of these add up to a healthy community.”

There is still work to be done. And under the Trump administration, that work has taken on a new urgency. In March of 2017, the EPA’s top environmental justice adviser, Mustafa Ali, resigned from his position when the agency’s new director Scott Pruitt proposed gutting the environmental justice program’s budget. The cuts would mean losing staff and funding for programs that primarily assisted low-income communities and communities of color, if not the elimination of the entire environmental justice program itself. Ali was a founding member of that office, and the EPA did not comment on whether or not his vacancy has been staffed as of yet.

“When I hear we are considering making cuts to grant programs… which have assisted over 1,400 communities, I wonder if our new leadership has had the opportunity to converse with those who need our help the most,” Ali wrote in his resignation letter.

Pruitt has also repealed numerous environmental regulations writ large that impact clean air, water, and other environmental contamination affecting all communities in the U.S.

“Our groups are already not very well protected by these policies and rollbacks,” says Franklin. “But if you take a look back and look at the entire system, can we ever say that our people were better off? It’s the same fights. The same struggles persist.”

As for Bullard, who has been fighting this fight since the 1970s, the Trump administration’s environmental policies are just one of many ups and downs he’s witnessed. Bullard points out that the environmental justice movement has also grown to recognize climate justice, an international movement that advocates for those who contribute the least to climate change in terms of emissions, but will be affected the most by changing weather patterns and access to food and water.

“Environmental justice did not originate from the government,” Bullard says. “It was born out of struggle in communities that face threats. So there will continue to be environmental justice and climate justice movements as long as there is injustice. In the end, I’m optimistic that we will get to justice and fairness for all.”