This story originally featured on Undark.

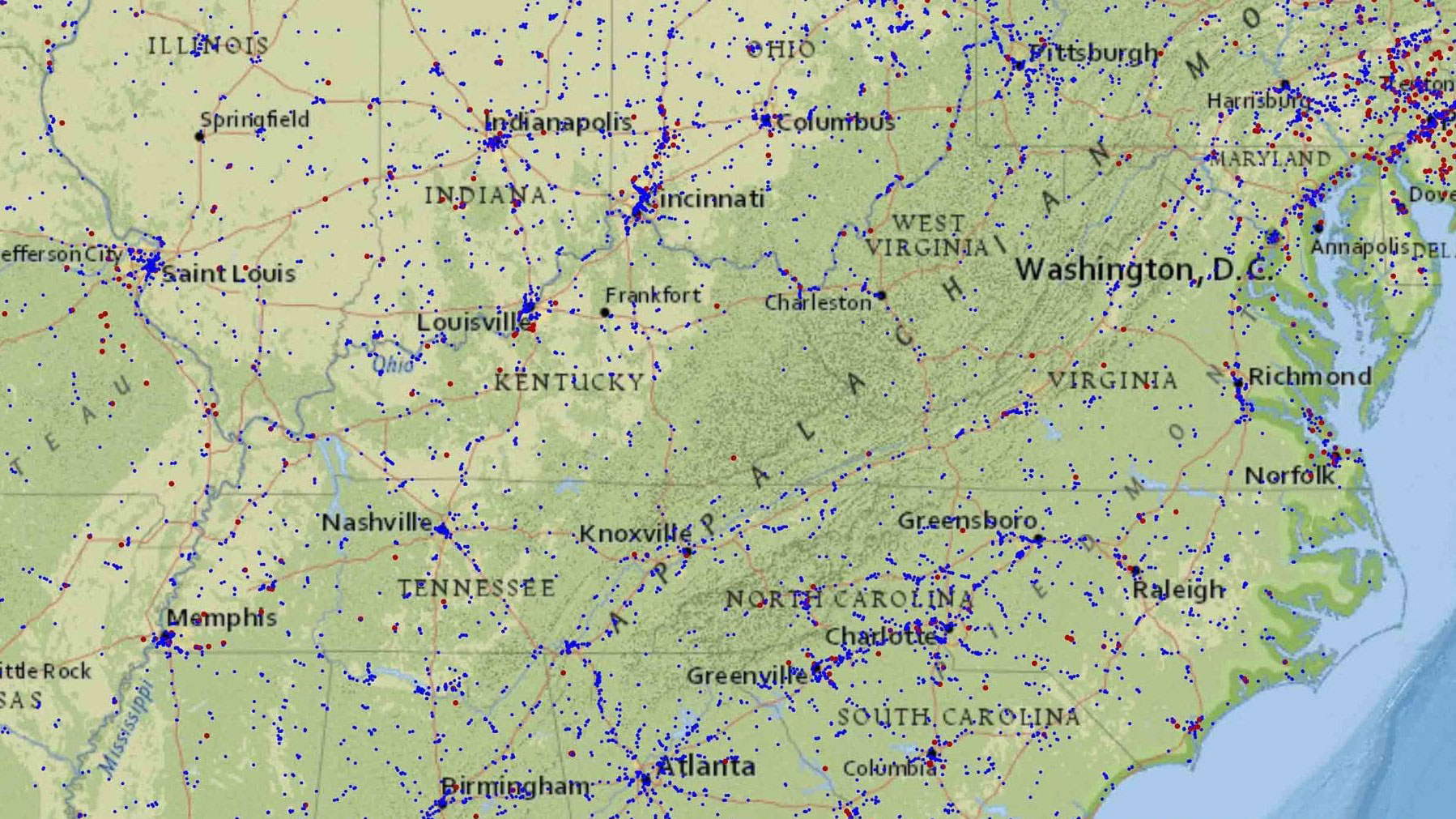

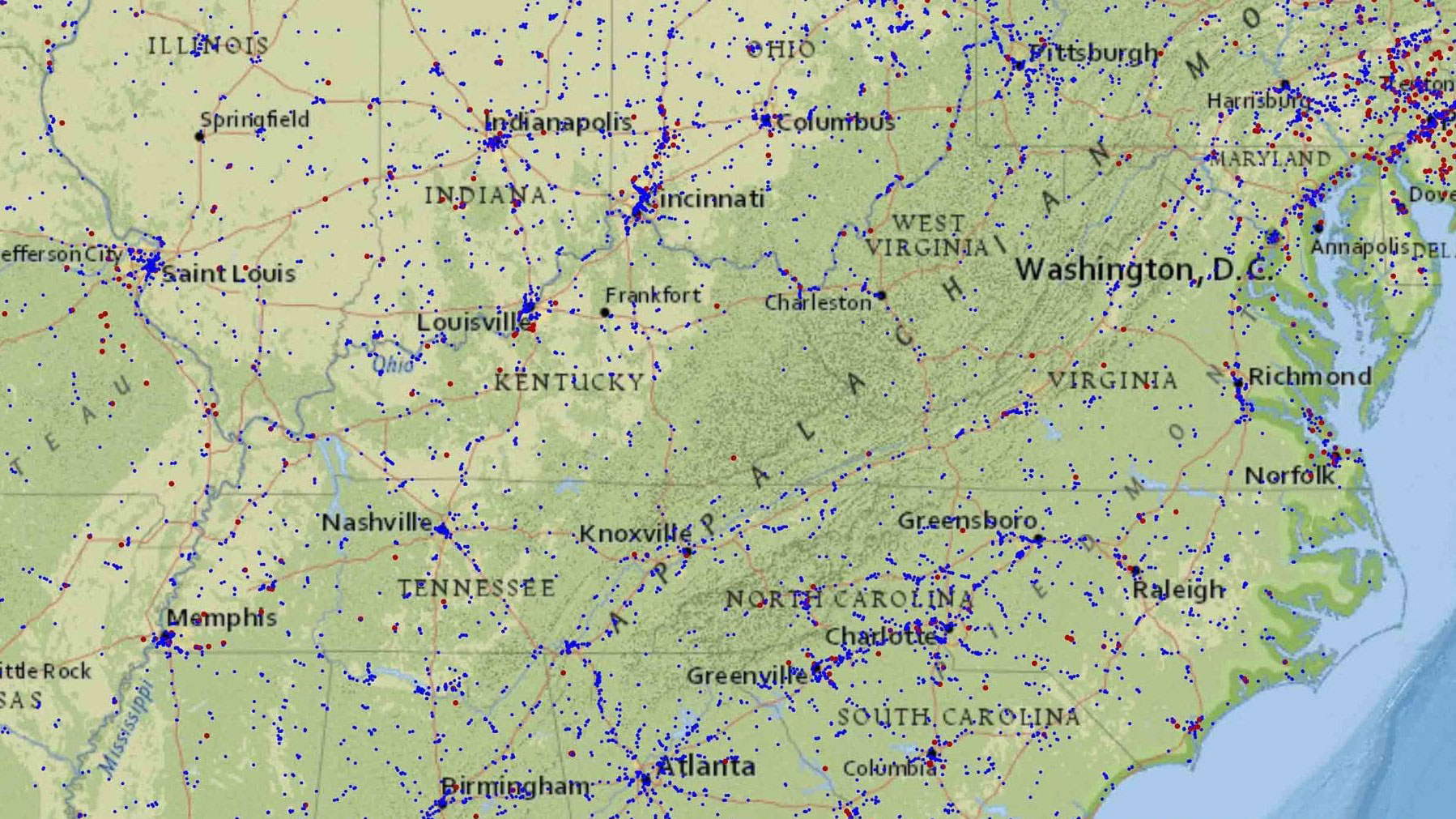

Fifteen years ago, the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM) launched Toxmap, a free, interactive online application that combines pollution data from at least a dozen U.S. government sources. A Toxmap user could pan and zoom across a map of the United States sprinkled with thousands of blue and red dots, with each blue dot representing a factory, coal-fired power plant, or other facility that has released certain toxic chemicals into the environment, and each red dot marking a Superfund program site—“some of the nation’s most contaminated land,” according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Toxmap allowed users to pull up detailed EPA data for each toxic release site, and to overlay other information, such as mortality statistics, onto those maps. And it’s precisely those capabilities that earned Toxmap a devoted following among researchers, students, activists, and other people keen to identify sources of pollution in their communities.

Those capabilities appear to no longer be available to the public.

Earlier this year, with little explanation, the NLM announced that it would be “retiring” the Toxmap website on Dec. 16, 2019. The library did not respond directly to queries on Monday about what was meant by “retiring,” but by Tuesday morning of that week, the Toxmap website had been taken down and visitors to the former URL were met with a message acknowledging the closure and pointing visitors to other potential sources of information. (An archived version of the old Toxmap landing page is preserved at the Internet Archive.) The decision to sunset the application has upset some of Toxmap’s most loyal users and raised concerns among environmental data advocates, who say that Toxmap’s demise would inhibit reliable public access to essential data about environmental hazards.

“I think it’s really sad that they’re getting rid of this,” said Claudia Persico, an environmental policy scholar at American University who studies the impact of pollution on children’s health, and who uses Toxmap in her research. That sentiment was shared by Chris Sellers, an environmental historian at Stony Brook University and a member of the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI), which monitors federal environmental data sources and advocates for greater public access. “It was stunning to me that the National Library of Medicine is actually retiring this pretty essential tool for our environmental right-to-know.”

NLM has offered only brief explanations for its decision. In a statement to Undark, NLM communications staff wrote that, in order to meet the goals of a new strategic plan, the Library “had to make some difficult organizational changes,” adding that “selected Toxmap data” could be found scattered among nine other U.S. and Canadian government websites. (The map includes data from Canada’s National Pollutant Release Inventory.) “Part of the decision was prompted by the increasing availability of the underlying data from their original sources,” NLM added. “Many sources such as the EPA, among others, offer several products that provide similar geographic information system (GIS) functionality.”

In particular, the EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance History Online site allows people to enter a zip code and view nearby pollution sources, along with some data about their toxic releases.

But those alternatives, researchers say, simply do not offer the same scope and simplicity as Toxmap. “Because this information has gotten so complex, and there’s so much of it, it’s very difficult for someone who’s not really trained in the area to navigate it,” said Sellers. “This tool actually cut through all the jargon, all the different interfaces that EPA, for instance, puts up before you get to the actual data that you’re interested in.”

Data-sharing tools like Toxmap have their roots in the 1980s, when a toxic gas leak at a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India, killed thousands of people. (Estimates range from 2,200 victims to more than 10,000.) In response to the Bhopal disaster, lawmakers in the United States called for legislation that would give Americans information about potential toxin sources in their communities, under a principle called “right-to-know.” The Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, passed in 1986, required companies using certain hazardous chemicals to report that information to the EPA, and for the EPA to make that information available to the public.

Much of that data came to form the backbone of Toxmap, which was launched in 2004 by the NLM, part of the National Institutes of Health. While this data was available in other formats, the NLM tool brought it together in one place and made it accessible to the general public. From the start, the tool “was developed to be easy to navigate and to understand,” a group of NLM affiliates wrote in a 2014 paper marking Toxmap’s 10th anniversary.

Since then, Toxmap has been used for everything from student projects to figures in academic papers. “It’s a great resource for teaching students,” said Sara Wylie, a science and technology studies scholar at Northeastern University and a cofounder of EDGI. Wylie uses Toxmap in her environment, technology, and society class. Among other things, she told Undark, the tool offers a vivid demonstration for students of how widespread toxic releases are in the U.S. The dots on Toxmap cluster around major cities, forming dense agglomerations in the country’s most populated corridors. They speckle quiet suburban neighborhoods, trail out along interstate highways, and dot the rural West. “It’s always shocking for students to find out that there are emissions happening near them, to see the complexity of them, and so it’s a pretty unique resource.”

Persico said she has found the tool helpful for research. “Being able to go to a place and actually see what the geographic landscape looks like, of the dispersion of pollution,” she noted, “is really, really valuable.” She uses the tool to visualize toxin sources and to generate figures for papers and for presentations. A new scientific paper she has pending publication in a journal, for example, uses Toxmap to show how EPA registered sites in Florida line up with population density statistics.

In 2018, the NLM launched a major update to Toxmap. But then, earlier this year, the Library announced that it would be shuttering the Toxicology Data Network, or Toxnet, the database collection that includes Toxmap. Many of its components would migrate to other NLM sites. But Toxmap, the organization announced, would be retired.

When asked about the concerns of researchers and other Toxmap devotees, as well as for more information about the upkeep cost and usage rate of Toxmap, the National Library of Medicine declined to answer questions, saying only in an email message: “We are not scheduling interviews regarding the sunsetting of Toxmap.”

This dearth of information has contributed to suspicions that the demise of Toxmap may have political motivations. “I hope people will understand what’s happening out there, that the government is gradually cutting off these very valuable tools that are really essential to our democracy,” said Sellers, citing trends under the Trump administration that include a reduction of mentions of climate change on EPA websites, and an administration effort to restrict the health data that can be used to inform government regulations.

Members of the public, he added, “have a right to know what chemicals are being released and stored, that are potentially dangerous, next door.”

Political suspicions aside, there is little evidence that Toxmap’s demise serves some higher political agenda—and indeed, leadership of the National Library of Medicine, including its director Patricia Flatley Brennan, predate the Trump administration. And in an email response to questions that arrived Tuesday afternoon, the library said that “the decision to retire the site was made by NLM, and not by the administration.” Still, the site’s closing does highlight that, more than 30 years after the passage of federal environmental right-to-know legislation, and more than 30 years into the internet era, finding simple, accessible, easy-to-use presentations of reliable pollution data can be difficult, if not impossible. Tools like Toxmap, Wylie said, could be clunky—even if they are, as she put it, “the best we’ve got right now.”

And yet the site’s basic principle — an interactive map, with toxic release sites clearly labeled, extensive health and demographic data ready for overlay, and extensive government data available at the click of a mouse — had a clear appeal. Asked what her ideal-world toxic data platform would look like, Persico laughed.

“Honestly,” she said, “I would build something like Toxmap.”

UPDATES: This story has been edited to reflect the actual removal of the Toxmap website, which was still available at first publication, and to add a response from the National Library of Medicine to the suggestion by some researchers that Toxmap was closed for political reasons. Undark may add further updates as additional information becomes available.

UPDATES: This story has been edited to reflect the actual removal of the Toxmap website, which was still available at first publication, and to add a response from the National Library of Medicine to the suggestion by some researchers that Toxmap was closed for political reasons. Undark may add further updates as additional information becomes available.