The tiny country of Wales on the western coast of Great Britain may now be home to one of the world’s most unexpected fossil sites. Scientists found an “unusually well-preserved” deposit of over 150 species from 462 million years ago. Interestingly enough, many of them have miniature bodies. The findings by an international team of scientists from the United Kingdom, China, Sweden are detailed in a study published May 1 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

[Related: These weird marine critters paved the way for the ‘Cambrian explosion’ of species.]

The “marine dwarf world,” as dubbed by the research team, is located in Castle Bank near Llandrindod, central Wales. Two of the study’s authors, Joe Botting and Lucy Muir, found the site in 2020. Castle Bank is a rare site where the soft tissues and complete organisms are preserved. These specimens help scientists observe how life evolved over time.

Similar fossil sites like the Burgess Shale fossil deposits in Canada date back 542 to 485 million years ago during the Cambrian period, when recognizable animals first appear in the fossil record. This period is known for a huge explosion of life on Earth. During the Cambrian, the origins of major animal groups still around today, such as mollusks, arthropods, and worms, occurred in what scientists call the Cambrian Explosion.

The fossilized time capsule from Castle Bank is from the middle of the succeeding Ordovician Period, about 462 million years ago. The Ordovician was a critical time in the history of life when extraordinary diversification of animals occurred and more familiar ecosystems like coral reefs began to appear at the end of the period. Until now, a big gap has existed between thes Cambrian and Ordovician eras. Some of the fauna found at Castle Bank dating back to the middle of this time interval will help fill in evolutionary mysteries about animal shifts over time.

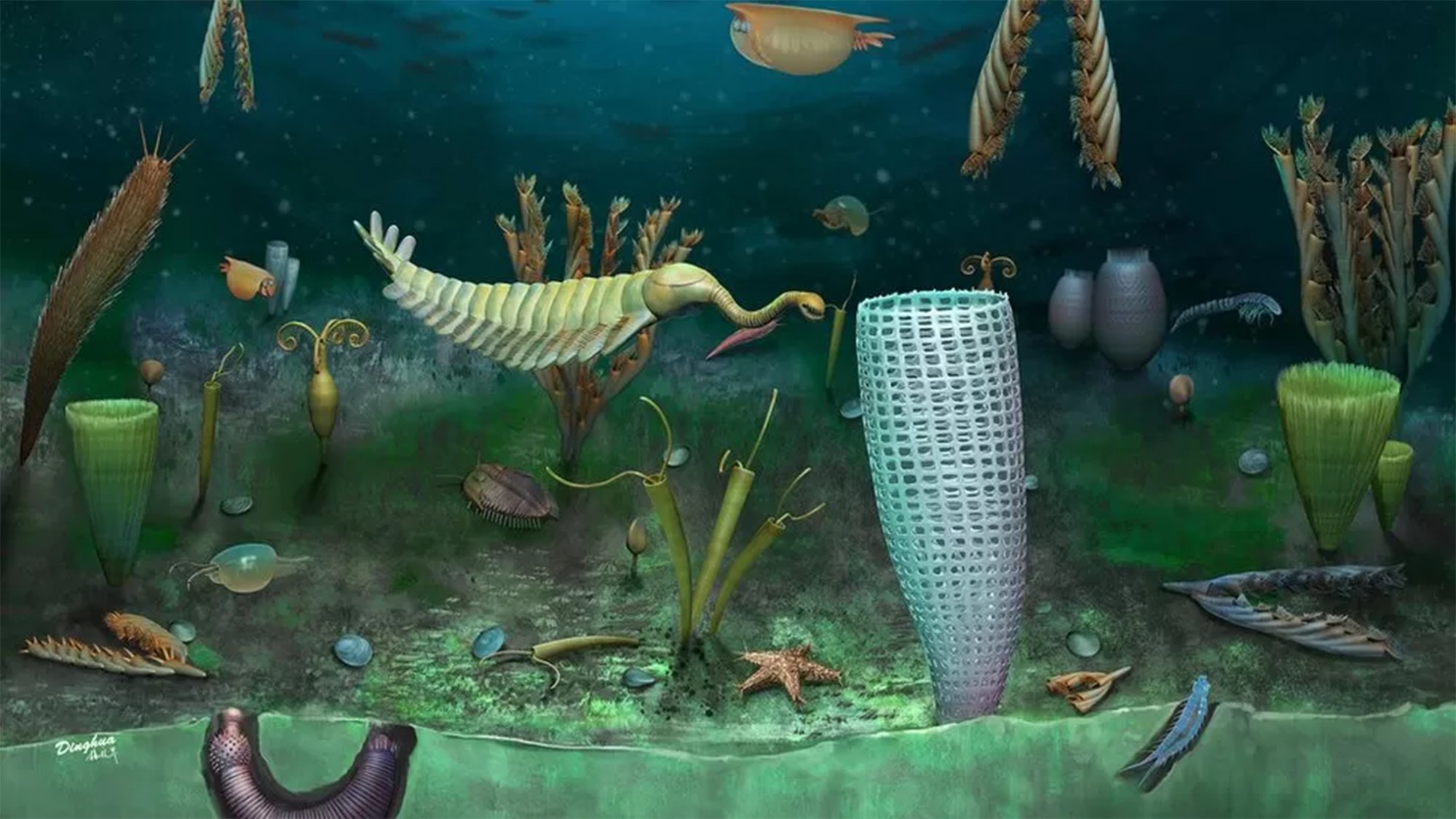

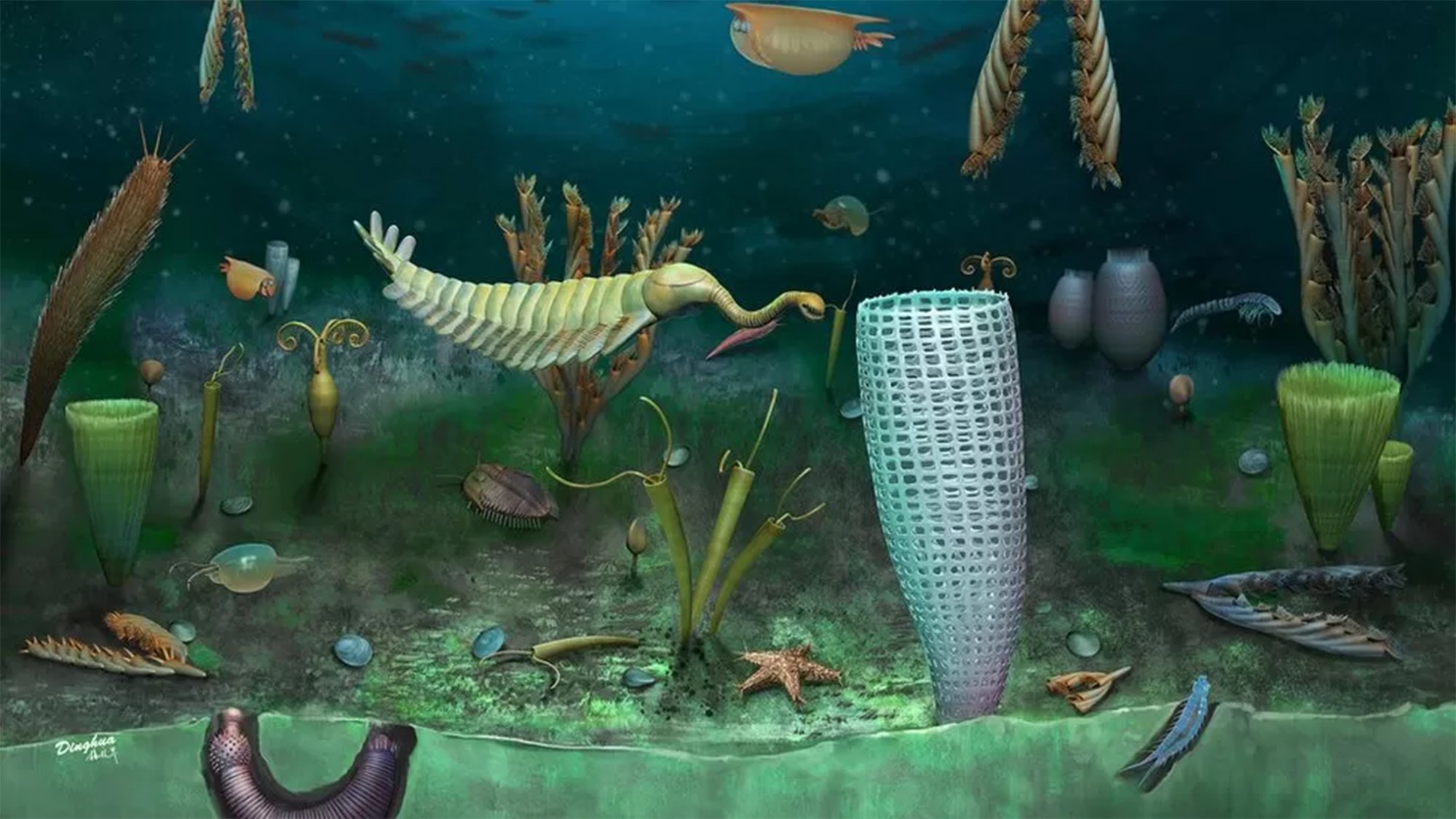

The more than 150 species found at Castle Bank are almost all new. Many are less than an inch long, but contain tiny details in their bodies. They range from arthropods like crustaceans and horseshoe crabs to worms, sponges, starfish, and more.

In some animals in the study, internal organs like digestive systems, the limbs of tiny arthropods, delicate filter-feeding tentacles, and even nerves have been preserved. According to the authors, exquisite detail like this is known from Cambrian specimens, but not previously from the Ordovician.

The range of fossils also includes several unusual discoveries, including unexpectedly late examples of animals from the Cambrian that look like the strange looking proto-arthropod opabiniids and slug-like wiwaxiids. Some of the early fossils also resemble modern goose barnacles, possible marine relatives of insects and cephalocarid shrimps, which have no fossil record at all.

[Related: This fossilized ‘ancient animal’ might be a bunch of old seaweed.]

“It coincides with the ‘great Ordovician biodiversification event’, when animals with hard skeletons were evolving rapidly,” Muir, a paleontologist and research fellow from the National Museum Wales, told the BBC. “For the first time, we will be able to see what the rest of the ecosystem was doing as well.”

These findings also have important implications for the evolution of sponges, particularly Hexactinellida. Also called a glass sponge, this animal is considered a transitional interval between sponges that the team have been studying for years.

“Despite the extraordinary range of fossils already discovered, work has barely begun,” Botting, a paleontologist and research fellow at the National Museum Wales and Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology Chinese Academy of Sciences, told the BBC. “Every time we go back, we find something new, and sometimes it’s something truly extraordinary. There are a lot of unanswered questions, and this site is going to keep producing new discoveries for decades.”