When Dominque Paul walks down the street, people stop and stare. Sporting silver go-go boots, a metallic wig and light-up dress, she looks like a David Bowie fever dream.

Paul’s outfit is more than just a fashion statement. It makes pollution visible. A device attached to her handbag measures airborne particulate matter and assigns a color to her dress based on the Environmental Protection Agency’s Air Quality Index. When the air is safe to breathe, her dress lights up green. When the air is contaminated, her dress turns yellow, orange, red or purple, depending on the level of pollution.

Paul debuted the dress as part of a residency with IDEAS xLAB, a nonprofit that uses art to raise awareness of public health issues. She has taken the dress out for walks in the South Bronx, which has some of the poorest air quality in New York City. Her goal is to spark conversations about air pollution.

Paul recently joined a walk organized by South Bronx Unite. The group’s president, Mychal Johnson, led a crowd through Mott Haven and Port Morris, neighborhoods in the South Bronx. They stopped every few blocks to talk about economic and environmental issues facing residents. Paul explained how the air monitor attached to her handbag measures fine particulate matter, microscopic bits of dirt and soot floating through the air. Vehicle exhaust is one source of particulates, which are small enough to enter the bloodstream and have been linked to lung and heart disease.

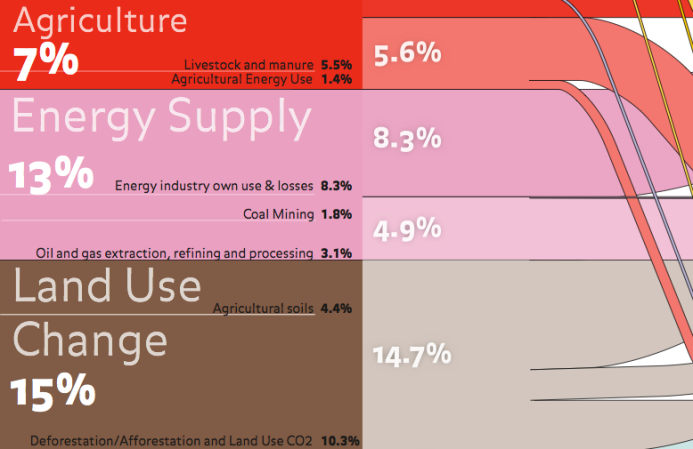

As she walked, Paul explained the Air Quality Index to those assembled. “Green is good,” she said. Yellow is worse. Orange means children and the elderly are at risk, and red means everyone may experience health effects. When it’s red, Paul said, “you might want to consider wearing a mask.” She raised her makeshift breathing mask like a flight attendant miming a safety demonstration.

“Right now, it’s fairly good,” Paul said, pointing to the lights on her dress, which oscillated between green and yellow. It was a weekend morning, she pointed out, with no rush-hour traffic, and the wind was blowing.

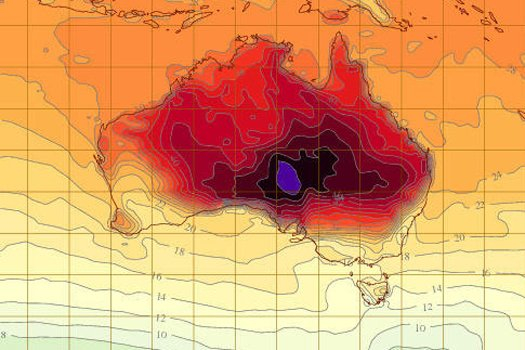

But, as the crowd paused on a walkway over the Major Deegan Expressway, Paul’s dress started to flicker between yellow and orange. The South Bronx is surrounded by freeways and overrun with diesel-powered garbage trucks. The asthma hospitalization rate among children living in Mott Haven and Port Morris is around three times the city average.

The air quality dress is not Paul’s only foray into wearable art. A previous dress changed color to represent the median annual household income in the surrounding neighborhood. Poorer neighborhoods registered red or orange. Wealthier neighborhoods registered yellow or green. Paul noted her median-income and air-quality dresses are nearly interchangeable. Poorer neighborhoods tend to be the most polluted, turning both outfits red. The heavily contaminated South Bronx is one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city.

Johnson raised his megaphone and shouted over the thunder of traffic. “We’re going to be doing monitoring of the air here, which we think is going to have extremely high rates of black carbon and [particulate matter] and other carcinogens that are found in vehicle emissions,” he said. Johnson pointed to a Fresh Direct distribution center being built along the river, which he said will bring more trucks to the neighborhood.

Johnson then introduced Markus Hilpert, associate professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University, who is partnering with South Bronx Unite on an air quality study. Like Paul, Hilpert wore a portable air quality monitor. He took the megaphone and explained that his study would measure air pollution and truck traffic in the area.

“What’s very unusual is that you have major traffic arteries running through the community,” Hilpert said, “which carry around 100,000 vehicles a day.” He snapped his fingers: “On average, every second — boom, boom, boom — there’s a vehicle!”

Paul stood next to Hilpert, mask raised to her face and dress blinking, drawing the attention of those assembled. “You can stop people on the street wearing this,” she said. “There’s something about technology and lights changing color that attracts people’s attention. And once you get their attention — if you link it to their environment — then they’ll tell you their stories.”

Owen Agnew writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture. You can follow him @OwenAgnew .