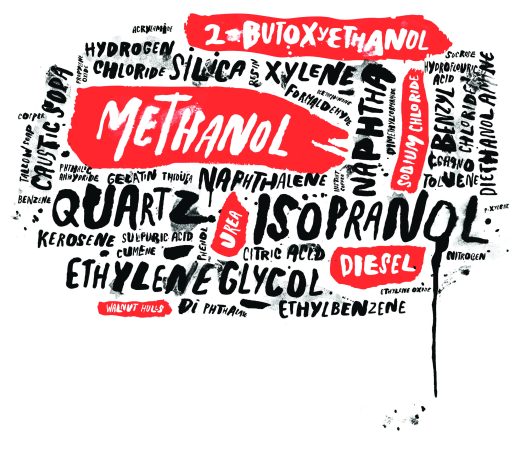

Under the banner of “trade secrets,” many oil and gas companies have refused to reveal all the chemicals they are injecting deep underground, at high pressure, to reach and extract deposits of natural gas and shale oil.

This has increased worries that chemicals from fracking fluids could contaminate underground aquifers and wells used for drinking water, while staying hidden because no one would know what to test for.

That could change in the coming year, however. The Environmental Protection Agency is opening a 90-day public comment period “on what information could be reported and disclosed” about fracking chemicals, “and the approaches for obtaining this information.” EPA apparently wants to consider carrots like “incentives and recognition programs” that might encourage companies to create improved (less toxic) fracking chemicals, as well as regulatory sticks that would force them to reveal their ingredients.

Some states already require firms to reveal cloaked ingredients to state officials or doctors if contamination is suspected, but still leave the general public in the dark, according to Climate Central.

EPA’s call for comments comes in part thanks to a 2011 petition by an environmental group, made under the Toxic Subtances Control Act. Earthjustice asked the agency to “require chemical manufacturers and processors to publish detailed information about the content of fluids used in fracking,” as well as “that those companies submit all health and safety studies available on those fluid mixtures,” according to Reuters.

Two related developments made big fracking news in April:

Houston-based Baker Hughes, one of the world’s largest oil field services companies, announced that it would disclose all the chemicals in its fracking fluids, whille keeping their chemical formulae proprietary.

A Texas family won $2.925 million in damages from Aruba Petroleum, when a jury found that fracking operations near the family’s 40-acre ranch had harmed their health, water supply, and property value.