Global Warming

The planet is heating up. Here's what that means for life on Earth—now and in the future—and what we can do to reverse the trend.

Latest in Global Warming

Environment

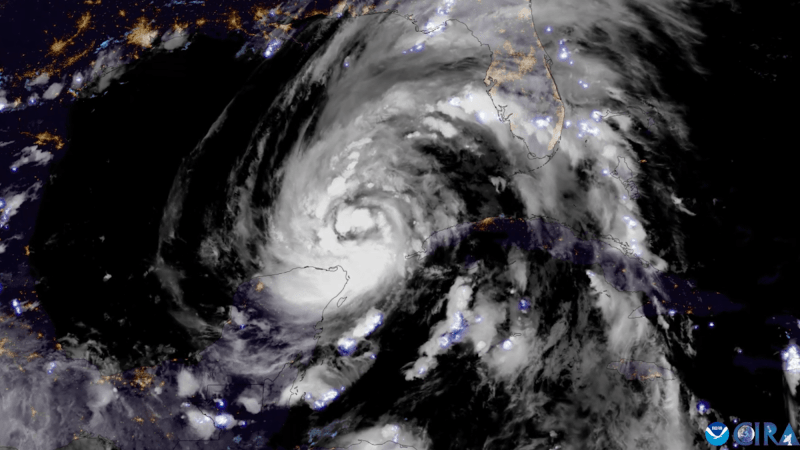

What Hurricane Helene looks like from space

Environment

Drought reveals a sunken village in Greece

Climate Change

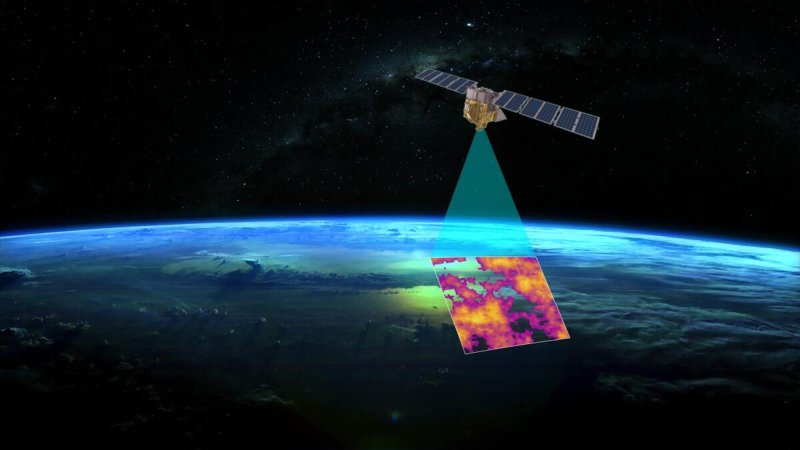

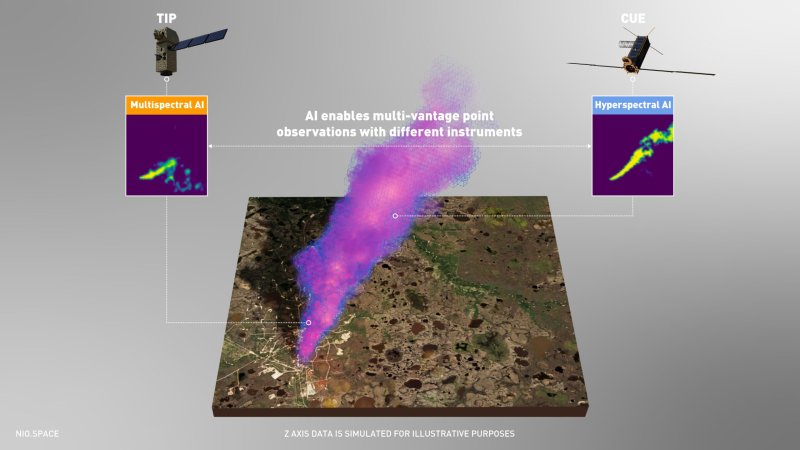

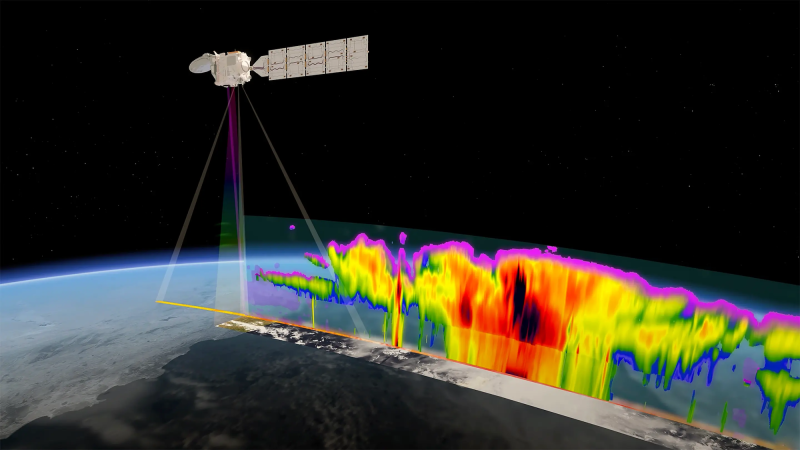

The ‘White Dragon’ satellite will keep watch over our clouds

Environment

Why are Alaska’s rivers turning orange?

Environment

Stronger hurricanes may call for a ‘Category 6’

Environment

Why scientists are studying aardvarks’ poop

Environment