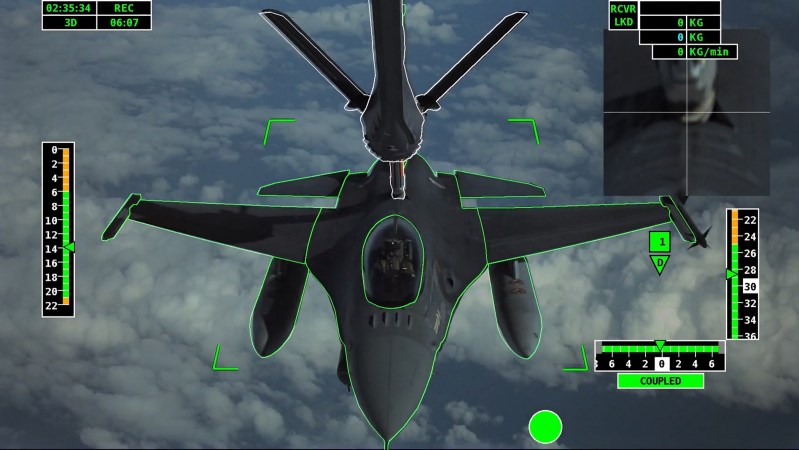

If you know how to drive a car, chances are you’ve spent some time in a driver’s ed vehicle with a teacher sitting next to you. The same is true, kind of, for Air Force fighter jet pilots. They learn in trainer aircraft: planes where a rookie and an instructor can fly together.

Last month, Boeing revealed the name of the aircraft that will be the Air Force’s new advanced jet trainer: the T-7A, a supersonic, 47-foot-long plane with pretty red twin tails. The company says the craft will be ready for delivery in 2023. So far, they’ve made just two of them.

Boeing designed the T-7 around the idea that two pilots will be sitting in tandem, one in front of the other. That’s the same as the aircraft it’s going to replace, the T-38, but the T-7 offers something new: stadium seating. That means that if the instructor is sitting in the backseat, they will have a clear view over the student sitting in front of them—a handy feature when a student is at the controls during landings or learning air-combat maneuvers.

Many driver’s ed cars have a brake mechanism on the teacher’s side; in the same vein, trainer aircraft like the T-7 have two sets of controls, so either person can fly the plane from their station. The tandem cockpits in the T-7, says the plane’s chief engineer, Paul Niewald, are “basically identical,” except that the front one boasts a head-up display.

Another perk? While the plane can be flown from either cockpit, the instructor can take over all the controls if they need to. “If the student is doing something dangerous with the airplane, the instructor pilot can eliminate the student inputs,” explains Dan Draeger, chief tactical test pilot at Boeing. (Each pilot has their own Aces 5 ejection seat, too; it can be set so that pulling one ejection handle triggers both seats.)

The goal of this advanced trainer, just like other trainer aircraft, is to get pilots ready for the current-generation fighter jets that pilots operate out in the field. “When you fly the T-7, you’re flying an airplane that feels very much like a front-line fighter like an F-16 or F-15,” Draeger says. (The “T” in the T-7 stands for “trainer,” and the “F” in those other planes means they’re “fighters.”)

And while some F-16s, nicknamed “vipers,” do indeed have backseats with flight controls, offering a spot for a pilot in training or even a journalist, Draeger points out that a trainer aircraft should be cheaper to buy and operate than a front-line fighter. In other words, it’s a cost-effective plane that mimics the nimbleness of a jet like the viper.

Boeing also designed the T-7 to naturally bring itself nose-down if it stalls, which can happen when the nose pitches up too much. “Even if the student pilot does everything wrong, eventually the pointy end heads towards the Earth, and the airplane starts speeding up again,” Draeger explains.

Advanced trainers have been around for decades: They prepared US pilots to aviate in World War II and are still wheeled out and flown at shows and races across the country. Last month, I strapped into the backseat of a 1942 T-6 aircraft—a plane with silver metallic wings that glinted in the bright sunlight. We lifted off a runway at Reno Stead Airport in Nevada, flew over the high desert, briefly rolled upside-down and right-side up again, then landed. The plane was an old warbird, so it didn’t have stadium seating, which meant my main view was the back of the pilot’s head.

“It’s the best trainer they ever made,” says Bill Muszala, who flies a similar 1940s-era plane called an SNJ-5. “By the time you think you got it conquered, it bites you in the butt.”

Aircraft like that T-6 I flew in—specifically a Texan AT-6C—are how American pilots learned their advanced skills before hopping into craft like the P-51 Mustang or B-17 bomber. “All these pilots that are trained during World War II—the Texan is an integral element of that story,” says Jeremy Kinney, who is an aeronautics curator at the National Air and Space Museum.

While I was in the AT-6C, I had old-school gauges to check out our airspeed and altitude. Student pilots and instructors in the Air Force who someday climb into a Boeing T-7 will have two touchscreens in front of them, whether they’re in the front or the back. The bigger of the two touchscreens, called the large area display, is 8 inches by 19. Pilots will be able to tap to see maps or information about the aircraft’s health.

“That enables us to make a more intuitive cockpit, so you don’t have as many buttons and switches,” says Niewald, the Boeing engineer. “This is just a natural transition for new pilots coming on board that are used to iPads and computer screens.”

Popular Science was on the ground (and in the air) in Nevada covering the Reno air races. Check out our gallery of aircraft at the event, a by-the-numbers breakdown of the high-speed aviation competition in the desert, and a look at the thrill of flying upside down.