Humans have been jumping, sliding, and explosively ejecting from imperiled airborne vehicles since World War I. But clearing crewmembers from doomed planes soaring as high as 80,000 feet—without killing them—has taken more than a century of refinement. Now, the most advanced ejection seats boast survival ratings above 90 percent. This is how we got there.

1914-1918: Balloon jumping

Cockpits had no room for storage, so the first military escape aids went to the balloon corps—where any attack could turn explosive. (Thanks, hydrogen gas!) Crews hooked harnesses to chutes attached outside the basket and tumbled out.

1916: Backpack bailing

Just 13 years after we first got into airplanes, pilot Solomon Van Meter patented a backpack-style contraption to help us hop out of them. An airman would jump from his plane and pull a ripcord, flipping open a tortoiselike aluminum shell full of silk chute.

1940–1945: Breakaway planes

Early stabs at ejection seats came in planes such as the German He 280 and the Do 335. The chairs used compressed air to fling people out of cockpits. In the case of the Do 335, when the flyer needed to bail, a second blast would jettison the tail and back propeller so the pilot wouldn’t hit them on the way out.

1941–1945: The rollout

Allied planes finally had exit strategies. Some aviators sat on packed parachutes that unfurled with a tug after they’d roll into the open air. Others donned harnesses that could quickly connect to chutes stashed around the cabin.

1947: Swift exit

Throwing crews clear of crashing crafts got tricky as jets sped up, so ejection experts Martin-Baker’s Mark 1 catapulted people at 60 feet per second. To start the action, escapees pulled down face shields over their heads. Small chutes called drogues stabilized seats until crew released personal canopies.

1953: Automatic deployment

Getting thrown free can knock you unconscious, so the second-gen Martin-Baker seat worked on its own. The unfolding drogue pulled pilots from the seat and deployed a personal chute. Sensors kept the main canopy closed above 10,000 feet, saving the slowdown for lower, easier-to-breathe air.

1956: Slide of doom

Ejection seats didn’t become immediately universal. The Douglas A3 nuclear bomber, for instance, had crew slide down a passageway behind the pilot, and pull their backpack chutes once outside. The approach earned the A3D, which carried three people, a nickname: the “all-three dead.”

1961: The low rider

Sometimes crew need to high-tail it when hovering just over the ground—or even sitting on the runway—leaving little time between exit and impact. Martin-Baker added a rocket pack for an extra boost. In one test, a pilot started from nada and shot up 200 feet for a slow, safe descent.

Late 1960s: A better handle

Once aviators donned helmets, there was no need to lower protective face screens before skedaddling. Martin-Baker found it speedier to trigger escape mechanisms with a handle between pilots’ legs. Hardware is in the same spot today—though in bombers, it’s on either side of the seat, out of the way of the flight controls.

Related: 10 huge machines that changed science

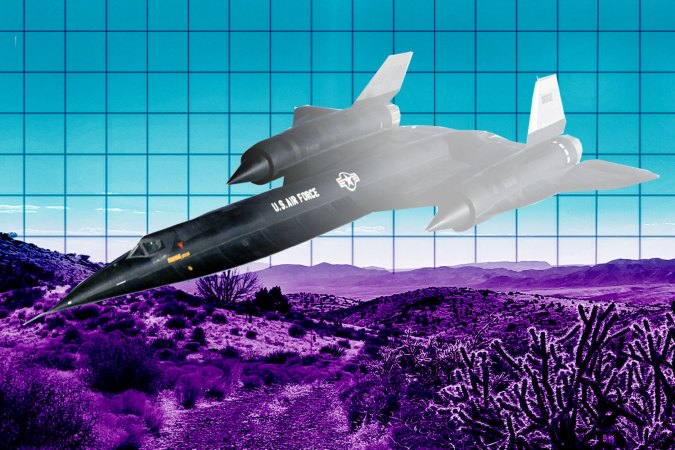

1975: Electric feel

McDonnell Douglas’ ACES II became the Air Force standard, replacing a hodgepodge of seats by different makers. It featured quick-firing, rocket-powered chutes, and was more reliable—the first to time ejection sequences electronically instead of using mechanical or pyrotechnic delays.

Present day: Universal design

Ejectors long catered to men between 140 and 211 pounds. Today, seats safely shepherd all sorts of bodies. For example, the ACES 5—now made by Collins Aerospace—has a spring-loaded system in its neck rest to support noggins as pilots hit fast airstreams, as illustrated above. It’s crucial for protecting more delicate frames, and lowers risk of spinal injury for all.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2018 Danger issue of Popular Science.