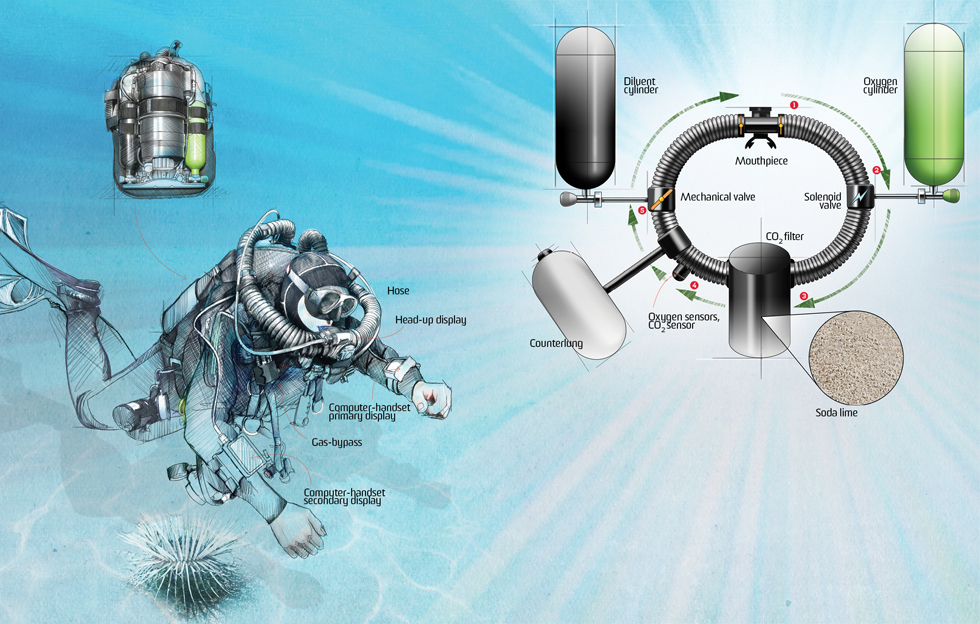

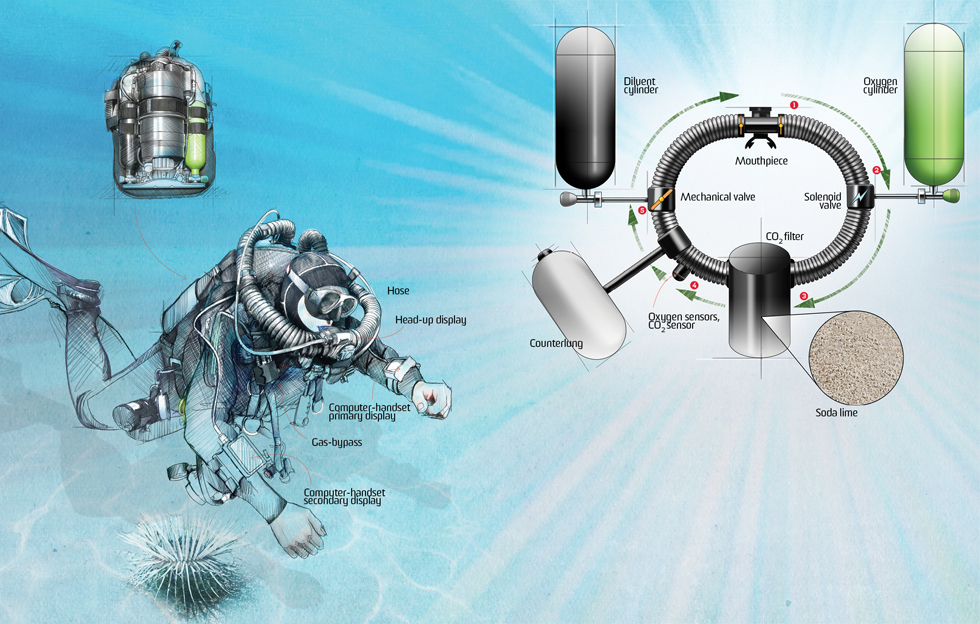

Conventional scuba systems have some major limitations. Divers using them must carefully monitor the depth and time they stay underwater and endure a series of lengthy decompression steps during resurfacing. Rebreathers recycle air, allowing divers to go deeper and remain underwater for longer, with shorter decompression on ascent. The Navy has used the devices for decades, but they were very expensive, and difficult to maintain and operate. In 2008, VR Technology introduced the Sentinel, a $12,000 rebreather with automated safety systems and full manual backup. Scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts and the National Museum of China in Beijing are already using it. This July, Hollis Gear will release the VR-designed Explorer, an even less expensive ($5,400) model made for recreational divers.

THE ESSENTIALS

Human lungs absorb only 5 percent of the oxygen present in air. Rebreathers remove the carbon dioxide from exhaled air and recycle and supplement the leftover oxygen and inert gases, such as nitrogen, back into the diver’s next breath.

1. EXHALE

A diver’s CO2-rich exhalation flows through a one-way valve, called a mushroom valve because of its shape, on the right side of the mouthpiece and travels down a hose.

2. OXYGENATE

Before the exhaled breath enters the main part of the rebreather, an electrical valve called a solenoid regulates the flow of gas from the oxygen cylinder based on oxygen-concentration data from an onboard computer. The oxygen mixes with the CO2-rich exhalations.

3. SCRUB

Next, the air enters the CO2 filter, a canister the size of a coffee can that holds about five pounds of absorbent granulated soda lime. Lime binds to the CO2 that flows through the filter but has no effect on oxygen or inert gases, allowing them to pass through unhindered.

4. MONITOR

After the scrubbed air leaves the CO2 filter, three oxygen sensors and a CO2 sensor monitor the gas’s chemical composition. Too little oxygen, and the rebreather’s computer tells the solenoid valve fed by the oxygen cylinder to open; too much, and the computer tells the solenoid to close.

5. INHALE

When the diver draws his next breath, he also draws the oxygen-enriched air into the counterlung, a flexible storage bladder. Near the counterlung, a mechanical valve senses if there’s sufficient air pressure for the diver to inhale the next breath. If the pressure is insufficient, the valve opens and an oxygen-nitrogen mixture from the diluent cylinder provides enough gas to pressurize the counterlung. When the diver inhales, he pulls the freshly mixed air from the counterlung through a one-way mushroom valve on the left side of the mouthpiece and into his lungs.

FAIL-SAFES

Two computer handsets strapped to the diver’s forearms and a head-up display placed in his line of sight show his oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in real time. If the rebreather malfunctions, the onboard computer instructs a motor to vibrate the mouthpiece, and red lights embedded in the mask flash near the diver’s right eye. A gas-bypass button hangs from each shoulder. The diver can add oxygen or diluent manually if the automated system malfunctions. If all else fails, divers also carry a bailout scuba tank.

SENTINEL

Max. depth 330 feet

Max. time underwater 2 hrs. and 45 min. at 330 feet

Weight 88 pounds

Number of safety steps required before dive 20

Time from concept to completion 10+ years

Story by Brooke Borel

Illustration by Beaudaniels