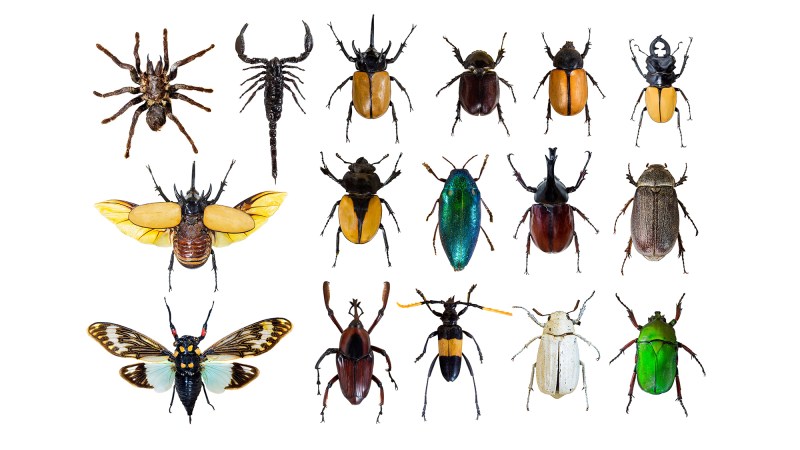

There are hundreds of bombardier beetle species on Earth, and you probably wouldn’t want to mess with any of them. They’re famous for spraying piping-hot jets of corrosive chemicals from the tips of their abdomens—effectively, their butts—to ward off predators like ants and praying mantises.

At least one species uses this notorious keister-blast to escape toad bellies and live to tell the tale, according to a new study published Wednesday in the journal Biology Letters.

“Ever since I started working on bombardier beetles, I knew their defense systems were really effective against predators,” says Wendy Moore, an entomologist at the University of Arizona who wasn’t involved with the recent work. “But I never really thought that it’d be effective in the stomach after a toad had eaten them.”

The study authors themselves were similarly surprised. “The escape behavior and predator tolerance amazed us,” lead-author Shinji Sugiura told Popular Science in an email. Sugiura originally discovered the beetles (Pheropsophus jessoensis) could escape toad stomachs in 2016 when he put the two animals together in his lab. “The toad easily swallowed the beetle, but it vomited 44 minutes later,” says Sugiura, who is an ecologist at Kobe University in Japan. “Surprisingly, the vomited beetle was still alive and active!”

To get a closer look, Sugiura and his colleagues collected bombardier beetles and two toad species near forests in central Japan. Back in the lab, they poked some of the insects’ butts with forceps to get them to use up all of their explosive juice. They then fed the toads either one of those ammo-less beetles, or one that was fully locked and loaded.

Of the toads observed in the study, 43 percent vomited after eating the armed beetles, but only 5 percent vomited up beetles-sans-juice. The researchers even heard the popping sounds of the beetles’ explosions inside the toads’ bellies before puking commenced.

The power of a bombardier beetle’s blast depends on its size and species, but no matter what, it’s hard to miss. “It’s kind of a squeaky pop,” Moore says. “You smell it, you feel it, you see it—the whole thing.”

Moore adds that the insects’ blasts aren’t exactly painful to humans, but they “definitely get your attention.” The pest-control company Orkin compares the sensation to touching a hot stove. But for the Japanese toads used in this study—which are only around three to four inches long—an inch-long bug with an explosive heinie can really pack a puke-inducing punch.

Even after the toads tossed their cookies, all of the vomited bombardier beetles survived, much to Sugiura’s surprise; some even after spending up to an hour and a half stewing in amphibian digestive juices. “This suggests that this bombardier beetle species may have evolved the ability to survive predators’ digestive systems,” Sugiura says, adding that his next project is to see whether the hardy bugs can survive other digestive tracts.

“It’s interesting that even if they’re swallowed they can cause the frog to vomit, and survive,” Moore says. “How many other things can do that?”