Drugs are the most common psychiatric treatment for depression. But about 40 percent of people fail to respond to this first-line of antidepressants. What to do? The answer to date has often been more and different drugs.

But transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a technique that can revive activity in neurons in the brain’s prefrontal cortex using an electromagnet, has been receiving more attention as a possible treatment for these stubborn cases of depression. In 2008, the FDA approved TMS for this purpose. Data since that point has been promising, but questions remain: How does it compare to antidepressant drugs? Is it cost-effective?

Research presented today (May 6) at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in New York suggests that the technique is perhaps better than previously thought. In the study, the researchers compared two groups: those who had received TMS after failing to respond to drugs, and those who were given new antidepressants after not getting better on prior meds. The finding: 53 percent of those receiving TMS had no or mild depression after six weeks of treatment, compared with 38 percent taking a new or augmented type of antidepressant.

The study also looked at the economics. It found that TMS therapy would cost about $10,000 per patient per year, which is considered quite affordable, according to study co-author Kit Simpson, an economist at the Medical University of South Carolina. Over the course of two years, TMS would actually become more affordable than the current default of additional rounds of drug therapy, said Dr. Mark Demitrack, a study co-author and chief medical officer of Neuronetics, which makes a widely-used type of TMS called the NeuroStar TMS Therapy System.

The data seems to suggest that TMS ‘might be more effective than drugs.’

The results show the technique is better than drugs for this type of depression, Dr. Demitrack told Popular Science.

“Until now there has been a lot of research showing its efficacy but mostly compared to placebo, not other treatments,” said Paul Fitzgerald, a researcher at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, who wasn’t involved in the study. “It is clearly very safe, better tolerated than medication and now the data seems to suggest that it might be more effective.”

But there are some caveats. It should first be noted that this was not was not a randomly-assigned, placebo-blind study, the gold standard in gauging how effective treatments are, said Dr. Philip Janicak, at Rush University, who wasn’t involved in the research. Rather, it compared two different groups of patients. The first group consisted of 307 patients who were treated with TMS at 42 clinics throughout the U.S., after failing to respond to drugs. The second group, or rather second pool of data, was taken from a previous nationwide study, completed in 2006, of patients who were given new antidepressant medications after failing to respond to previous drug therapy. The patients in the latter group were chosen to match the former group as closely as possible, on measures such as sex, age, severity of illness, etc.

Another factor to consider is that most (about 90 percent) of the patients receiving TMS were still taking their old antidepressants, Dr. Janicak added.

That said, Dr. Janicak has been treating patients with TMS for 15 years, and has seen the technique turn around people’s lives. “I have to say I am amazed… we are seeing very significant improvements in these patients,” he told Popular Science. Dr. Janicak’s work has shown that about 55 to 60 percent of patients who have failed to respond to antidepressants respond to this technique, and see at least a 50 percent improvement in measures of their depression. About 35 percent of those patients have “remitted,” with enormous reductions in measures of depression, and some are no longer clinically depressed.

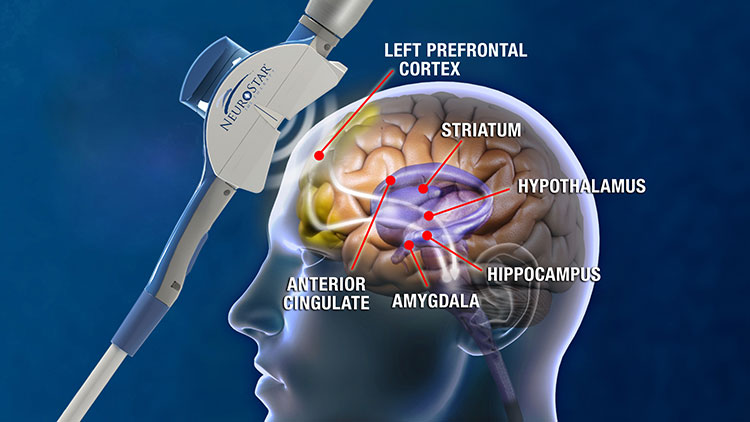

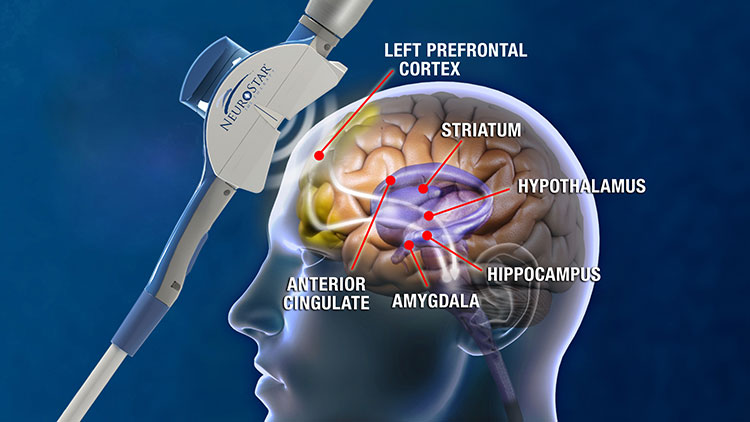

In TMS therapy, an electromagnet is applied to the left side of the forehead. This induces currents in neurons in the left prefrontal cortex–where brain imaging studies have shown a deficit in activity in depressed patients. It is thought that this can induce activity and blood flow to this area, but also causes changes in areas deeper in the brain (responsible for mood regulation) to which neurons in the cortex connect. Side effects of TMS tend to be mild, especially compared to antidepressants, and the most common complaint is a mild headache, Simpson said.

Exactly how TMS works is a mystery, Dr. Janicak said. But the same can be said of antidepressants, he added.