Once cars drive themselves, how will their bored human passengers spend their time—and fight off motion sickness? Instead of staring out the window at the landscape, perhaps, thanks to virtual reality, the quotidian scene could be filled with simulated zombies. That’s the idea behind a new patent application from Apple, which describes various ways that VR systems could be tied into an automobile.

The Apple patent focuses on incorporating VR into a car in such a way that it could help prevent motion sickness, or monitor for it and then try to mitigate it. Anyone who has ever felt car sick in the back seat may feel nauseous at the mere thought of donning a virtual reality headset—a technology that itself has had a reputation for making people puke.

To understand the idea behind the patent, it helps to first consider the unpleasant roots of what causes motion sickness. The main explanation is known as the sensory conflict theory: if your eyes tell you you’re not moving, but your inner ear senses that you are, you might feel sick.

“A sense of balance is different from all your other senses,” says Dr. Steven Rauch, a physician and the director of the vestibular division at Massachusetts Eye and Ear hospital. Your sense of smell, for example, comes just from your nose. Your sense of balance, though, is a combination of the organs in your ears that monitor how you move your head, what your eyes tell you about what’s around you, and what your muscles and joints take in from your environment (like what you feel if you’re standing on the deck of a moving ship).

Motion sickness can hit people when those various inputs to your sense of balance disagree. Sitting in the backseat of a moving vehicle and reading a book can spark nausea because your eyes aren’t seeing motion, but the rest of your body is feeling it.

Avoiding that sensory conflict is the idea behind Apple’s patent application. The authors theorize that if a person riding in a self-driving car wanted to work on their computer or read a book during the ride, they could start to feel sick if they were staring at a motionless laptop. In one scenario, the company suggests that material could appear as if it’s in front of the vehicle, “so that the virtual content appears as a distant object stabilized,” but at the same time, “visual cues of the real environment are moving in the field of view of the passenger.” That setup could ideally cut down on motion sickness.

In an even more extreme example, the patent application suggests that if everyone in an autonomous car is a passenger, why would you even need windows? In that sense, the car would be more like a submarine, and a virtual reality system could instead show passengers what’s outside, or a simulated version thereof, to prevent motion sickness—or even make them feel like the vehicle they’re riding in is bigger than it actually is. After all, if we’re all riding around in a self-driving pods someday, perhaps strapping on a VR headset that can match virtual scenes to the pod’s real motions could help prevent sickness, and maybe even make the journey fun.

But for a system like this to actually prevent nausea, it’s crucial that the VR tech works seamlessly with the vehicle’s motion. “It’s only going to help if it shows them what their body is feeling,” he says. In other words, if the trip a passenger sees in the virtual world doesn’t match what their body is experiencing, vomit bags may be in order.

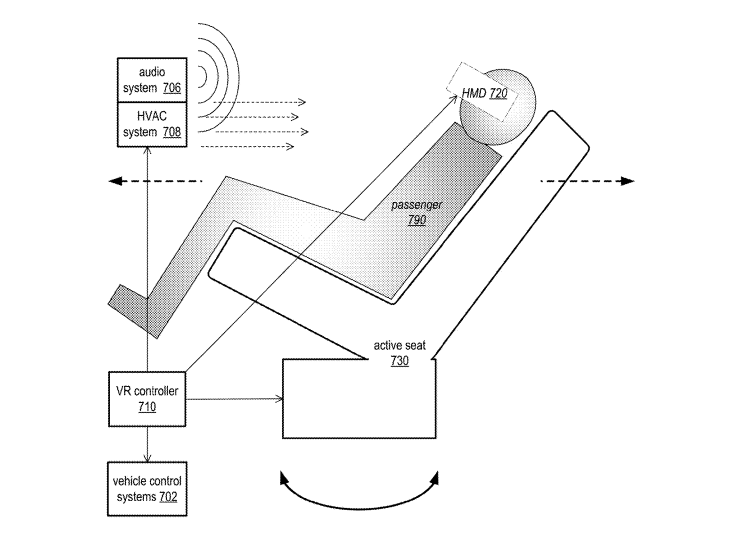

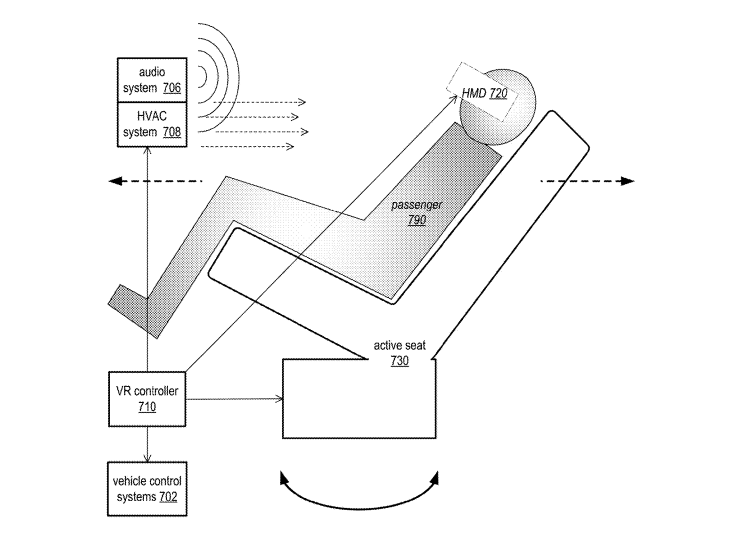

But the patent application also suggests some truly creative possibilities that emerge when you tie VR into a car’s system. For example, the car’s ventilation system could simulate wind in a virtual environment. Or the passenger could feel as if they’re hang gliding, or floating down a river. The VR system could even simulate “driving through a post-apocalyptic wasteland with zombies attacking,” all while the real car ride was simply through a boring old regular city, according to the patent. Alternatively, instead of zombies, the cityscape outside could be swapped out for London. In all cases, the car’s movement can add something to the virtual experience that a motionless couch in your living room cannot.

“I do think we’re going to be spending a lot of our time using VR and AR systems in our smart cars, because otherwise it’s pretty boring,” says Walter Greenleaf, a behavioral neuroscientist and visiting scholar at Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab. “It’s really a perfect space,” he adds, because it is enclosed.

“I think it’s a great approach,” he adds. “But I think that there’s more work to be done to understand how it can be best applied.”

One motion sickness solution remains decidedly low-tech, whether you’re in a car or on a ship: Look out the window or windshield of the car, or at the ocean’s horizon, and put the book or gadget down.