We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

Remember that video we posted on Monday about the paraplegic college graduate who used an exoskeleton to walk across the stage? In addition to making us shed grateful tears for the advancement of technology (whew, robotic tech isn’t evil after all), it prompted momentary visions of a future where disabled people have ready access to bionic limbs, super-strong exoskeletons, electric eyes and stair-climbing wheelchairs. Just take a look at the technology in our archives to see what the disabled had to choose from during the greater part of the 20th century.

Click to launch the photo gallery.

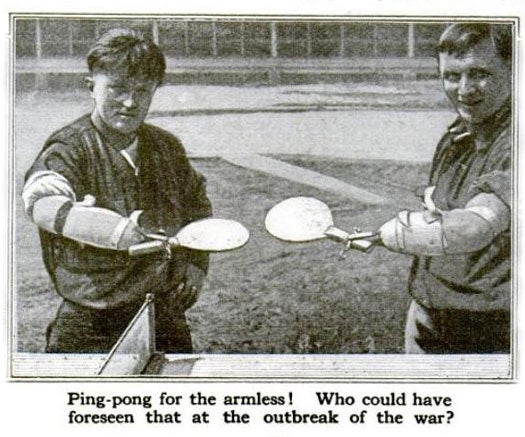

Thanks to World War I and the polio epidemic, the 1920s saw an influx in technology designed for the limbless and the paralyzed. Millions of soldiers returned home unable to walk or to use their hands, thus dooming themselves to lives on the street or under state care. Sensing a need for more dignifying career options, inventors produced a slew of special crutches and prostheses to help wounded veterans get on with their lives. Crutches equipped with swing seats (to relieve arm strain), prosthetic arms that could attach to shovels, and typewriters that could be operated with a steel arm all served to ensure that the disabled lived to their fullest potential.

Wheelchairs underwent vast improvements during this era (and in the following three decades) as manufacturers worked to make them motorized, easier to operate, and more adept at navigating bumpy terrain. Although the motorized wheelchair wasn’t officially invented until after World War II, we found a prototype in 1920 that looks as fancy as a Ford Model T.

Technology for the blind and the deaf also feature heavily in our archives, where we cover several decades’ worth of valiant efforts to invent artificial eyes and vibrating sensors. To help the blind navigate safely, one group of students invented an “echo flashlight” that emitted sound waves near obstacles. Meanwhile, a psychologist from Northwestern University developed a pocket watch-shaped device that turned speech patterns into patterns of vibration. Presumably, a (dedicated) deaf person could learn to interpret these vibrations as full sentences.

Impressed yet? Click through our gallery to see the wheelchairs, steel arms, and portable sensors developed to make live easier for people with disabilities.

Sit-Down Crutches: August 1918

In addition to killing millions of military personnel, World War I sent home scores of soldiers with debilitating injuries — namely, with a compromised ability to walk. Anybody who’s ever had to use crutches knows how much pain they inflict on your armpits, hence the invention of crutches that let you sit down while hobbling around. The image pictured left shows a pair invented by Walter Clifford of London, who installed a small swing to the arm supports of his crutches. The seat, which resembled a bicycle saddle (or for what was presumably the budget version, a pad on springs), could be adjusted according to the user’s height or be removed when not needed. You could also strap the crutches to your chest, leaving your hands and arms free to move around. Read the full story in “Now the Crippled Soldier Can Do His Walking Sitting Down”

New-Fangled Prosthesis: November 1918

After reaping medals for their heroism, it wasn’t uncommon for disabled World War I soldiers to end up on the streets or as charity cases, destined to spend the rest of their lives basket-weaving or begging for change. Anticipating the end of the war, the Red Cross, the Federal Board of Vocational Education, the Surgeon-General’s office and several other non-profit groups pursued measures to place disabled soldiers in jobs that would keep their dignity intact. This of course involved developing prosthesis to ease their transition to normal life. The man pictured on the left is wearing a “chuck” arm that could be fastened to a variety of appliances: utensils, shovels, boxing gloves, and pencil holders, to name a few. The artificial arm, which was made of steel wires and rawhide cords, didn’t work as well as a natural arm, but it showed wounded veterans that they didn’t have to take careers in piano-tuning or chair bottom-weaving to survive; they could be farmhands or assemblymen if they wished. Read the full story in “Crippled But Undaunted”

New Electric Wheelchairs: May 1920

While electric-powered wheelchairs were officially invented by George Klein during World War II, their origins are rooted a couple of decades earlier, when people were just beginning to incorporate electricity in their daily lives. This battery-powered model was “so easy to drive that an invalid can manipulate it,” and it moved slowly enough to reduce the risk of accidents. Pulling the small power lever on the right-hand side would start the chair, would moving the longer lever back and forth would regulate its speed. Read the full story in “An Invalid’s Electric”

Rolling Desk: December 1921

Nowadays, plenty of schools have elevators, ramps and handlebars to accommodate the disabled. This wasn’t exactly the case in December 1921, the height of the nationwide polio epidemic. We reported 1700 disabled children in New York City schools alone, making it all the more imperative that administrators find some way to enable their participation in regular school activities. One solution was this rolling desk, which had a special adjustable support for the legs. Read the full story in “Rolling Desk For Crippled Children”

Hearing With Your Hands: December 1925

Will the deaf one day “hear” through their hands? We don’t mean through sign language, but through a small device that sends vibrations through the palm. Dr. Robert H. Gault, professor of psychology at Northwestern University, developed the mechanism as a means to allow the deaf to hear by touch. Ideally, deaf people would learn to match vibration patterns with speech patterns, which “is scarcely more difficult than is learning what similar combinations of vibrations mean when they fall upon the ears of a normal person.” The device, which vaguely resembled a telephone receiver, operated much like one, except that it used touch-based vibrations instead of sound waves. In his tests, Dr. Gault successfully taught five deaf subjects to understand 15 sentences made of 90 one-syllable words. The scientific community was so excited by Gault’s discoveries that he was recruited by the National Research Council to continue his work on the device, but presumably, it never really caught on. Read the full story in “New Instrument Enables the Deaf to Hear with Their Hands”

A Photographer’s Wheelchair: April 1939

Speaking of limitations, David T. Dickinson, a former fire insurance expert at Cambridge, Massachusetts, didn’t let infantile paralysis stop him from pursuing a love for photography. Since Dickinson’s specialty was fires, he needed a way to get to the scene (and safely back) before the fire department could put out the flames. The solution? A motorized wheelchair, furnished with a siren and a spotlight, that could be easily maneuvered to accommodate Dickinson’s camera angles. Read the full story in “Photographs Fires From a Wheel Chair”

Echo Flashlight: September 1947

Bats use echolocation to navigate darkness, and while human beings aren’t capable of emitting those same signals, a group of City College undergraduates developed a handheld device that could do virtually the same thing. Their “sound flashlight” would emit a focused beam of sound that would only become audible when it hit an obstacle. To use the flashlight, you’d simply direct it forward and wait until the sound beams reflected from a tree or a lamppost. The device came with an audio oscillator, a small headphone unit (which would convert electrical oscillations to sound), and a parabolic reflector. Read the full story in “‘Echo Flashlight’ Helps the Blind Find Their Way”

Mechanical Page-Turner: April 1951

Reading a book can alleviate the boredom of being bedridden, but even that’s a little tough when you’re incapable of turning a page. That’s why Frank Reck of Flushing, NY, developed this mechanical arm. The device, which was designed for both bed and wheelchair patients, could accommodate both books and magazines, and was powered by a small AC motor beneath the tray. To use it, patients would strap the operating switch to their chins so that a simple nod would prompt the machine to start turning pages. An adhesive roller would lift the page while a metal rod would push it across. Then the finger would move in front of the arm to slide the page off the wheel. The arm would move back in place, ready to turn another page. Read the full story in “Mechanical Arm Turns Page For the Handicapped”

Motor Chair: June 1954

We can’t imagine that it would have been easy being a paraplegic during 1950’s-era New York (or for that matter, New York today), but M. Arnold Lerman, pictured left, found a way to make it work. His Curb Stepper, a wheelchair that could climb up and down the curb, could shuttle Lerman across town at 10 to 15 miles per hour. It could also travel in sand and snow, aided in part by a two-cylinder engine with a self-starter. Now, if only this thing were allowed on the subway… Read the full story in “Motor Chair Climbs Up and Down Curbs”

A Suitcase For the Blind: June 1955

A few years after the sound flashlight’s debut, Thomas A. Benham and Clifford M. Witcher, both blind since infancy, worked on an electronic eye that could also sense when obstacles were ahead. Unlike the sound flashlight, however, Benham and Witcher’s devices used invisible infrared light beams instead of sound beams — it turns out that the latter compromises a blind person’s ability to hear incoming dangers, like cars. For awhile, Benham and Witcher worked together; Witcher focused on a curb locator, while Benham focused on an obstacle detector. When their approaches started clashing, though, the two split up to pursue their own approaches. Witcher’s device, the “curb locator,” would shine a tiny spot of light on the ground a few feet ahead. A photocell above the lamp would “see” the light spot on level ground. When the light spot disappeared under a curb, an alarm would go off, sending vibrations to the blind person’s hand. Read the full story in “Electronic Eyes For the Blind”