It looks like the U.S. is going to retain its measles elimination status, if only by a thread.

We officially got rid of endemic measles back in 2000. That means that while lots of people still get measles in the U.S., every case since 2000 has been tied to some outside influence. A visiting traveler or a citizen returning from abroad can easily bring the virus into the country, and since it infects 90 percent of the people it comes in contact with, the disease spreads. But as long as those outbreaks calm down before the contagion can gain a firm foothold, the country has still technically eliminated measles.

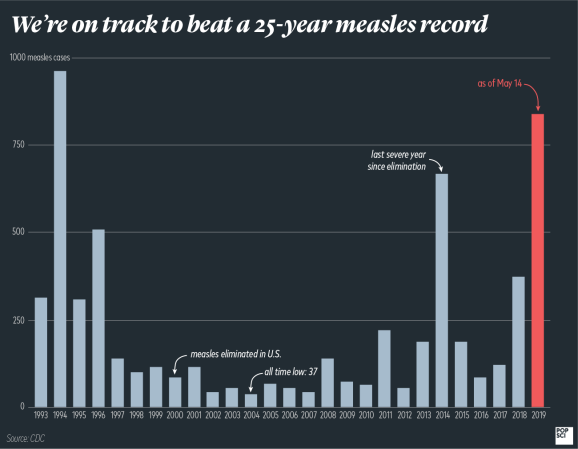

But 2019 has put that status to the test. So far this year we’ve had 1,243 cases, which is staggering compared to annual totals from the past couple decades, most of which didn’t even top 400. But while the number of cases is certainly concerning from a public health standpoint, our elimination status has more to do with how long each outbreak of the virus—a cluster of cases tied to a single source—persists before fading out. The World Health Organization doles out elimination status, and to qualify a country has to be free of endemic measles—meaning cases that have been transmitted from person to person inside the country’s borders—for a full 12 months. The U.K. already lost theirs this year.

Here in the states the key date was October 1, since that was the start date of the measles outbreak in New York’s Rockland, Orange, Sullivan, and Westchester counties in 2018. All told, 406 people were infected in that outbreak alone. It was only today that the state’s Department of Health was able to confirm that it had been more than 42 days (that’s two full incubation periods, just to be safe) since the last measles case tied to people in that original cluster. There are a few isolated measles cases in those counties, but none are related to the main outbreak. In a statement, NYS Health Commissioner Howard Zucker chalked the success up to several measures the state took to stop the spread. Physicians in New York now have more limits on granting medical exemptions to school vaccination requirements, and can’t grant non-medical exemptions at all.

The Centers for Disease Control also released a statement, noting that “the end of the New York state measles outbreak is a credit to the great work by local and state health departments, community and religious leaders, and other partners.” But the statement also warned that this past year’s outbreaks (and ongoing cases tied to international travel) should serve as a grave reminder of the importance of vaccination.

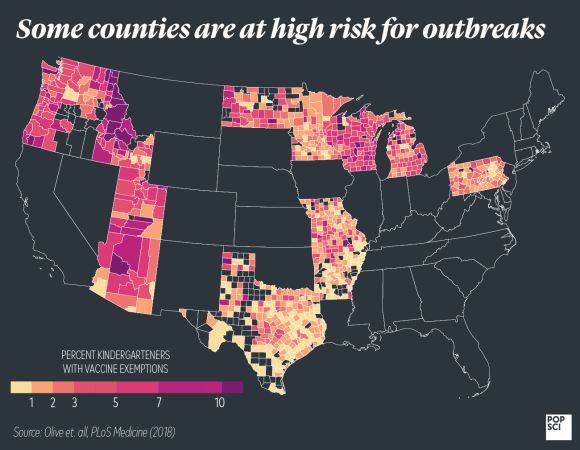

So are anti-vax movements to blame? It’s certainly true that exemption rates have gone up, especially in certain areas, which indicates more parents are choosing not to protect their kids with vaccinations. The truth, though, is that we’ve never really had high enough vaccination rates—either in the U.S. or worldwide—to stop measles. And that’s not to mention lack of access many people have to vaccines.

We came out of this outbreak with our technical record unscathed, but that shouldn’t come as a relief. This is a warning sign: If we don’t get our vaccination numbers up, we could face outbreaks at this scale—or worse—every year.