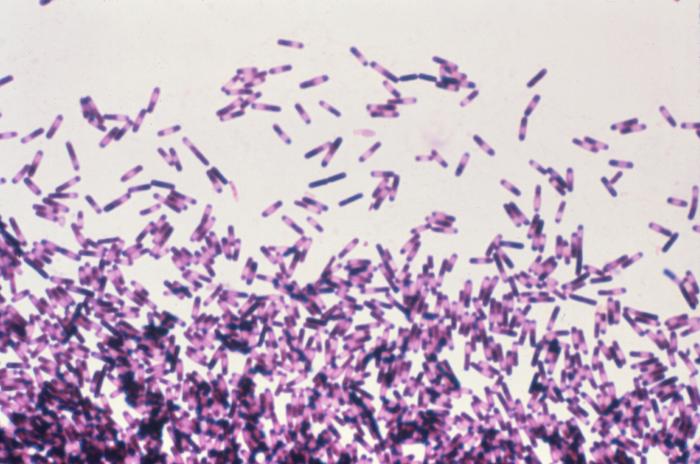

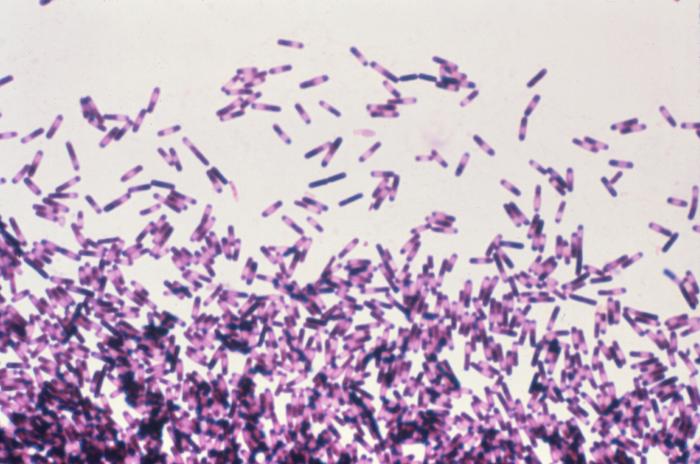

Patients are at constant risk of picking up an illness during a hospital stay, partly because they’re trapped in a building with other sick people who harbor all kinds of pathogens. One particularly notorious hospital-acquired ailment is Clostridium difficile colitis, an intestinal infection caused by bacteria. Most C. diff infections happen after a patient has received antibiotics to treat a separate problem. The antibiotic upsets the gut microbiome, allowing C. diff bacteria to take over. The result: a potentially deadly infection causing contagious diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain.

A new study in the October issue of the American Journal of Infection Control suggests that C. diff hospital cases in the United States nearly doubled between 2001 and 2010. The study examines hospital codes for C. diff from the US National Hospital Discharge Survey, which is taken each year by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Although the survey only represents around 150 hospitals, some fancy statistics extrapolate the information to represent 2.2 million adult patients.

According to the paper, there were 4.5 C. diff infections per 1,000 adults discharged from hospitals in 2001 and 8.2 per 1,000 in 2010. (C. diff causes about 14,000 US deaths annually.)

How did C. diff infections increase so much over a decade? One likely explanation is an overuse of antibiotics, says Kelly Reveles, an assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin and lead author of the study: “Antibiotics are still the primary risk factor for C. diff, and there is still a lot of unnecessary antibiotic use in this country.”

Reveles points out other factors that may contribute to the increase: the popularity of a class of heartburn drugs called proton pump inhibitors, which have been linked to an increased risk of C. diff infections; an aging population, since older folks are more apt to get C. diff; and an increased awareness of the infections in general.

The good news is that the sharp increase in cases leveled off between 2008 and 2010. The authors say this may be the result of new antibiotic stewardship programs, where doctors and pharmacists monitor hospital patients to confirm the need for an antibiotic and to make sure they are prescribed the right one (not all antibiotics can treat all infections).

There are limitations to the new study. The survey doesn’t include lab tests confirming the C. diff diagnoses, for example, which means that although the information may be accurate, there is no way to be sure. And because the survey only covers hospital-acquired C. diff infections, it doesn’t consider similar infections that are picked up in the surrounding community, which could skew the overall trends. “It probably underestimates the total burden of C. diff infections,” says Reveles.

Collectively, all the C. diff infections contribute to a boost in antibiotic-resistant strains of the bacteria, which are exacerbated by unnecessary antibiotic treatments. As these infections become more common, doctors are turning to new treatments, including fecal transplants, which have around a 90% success rate.

Reveles is currently working with a smaller—but richer—set of data from the Veterans Health Administration, which includes C. diff diagnoses as well as lab results and treatment information, which may fill in the gaps on overall infection trends as well as antibiotic effectiveness.

So how about C. diff, readers? Have you had it? Known anyone who has? What do you think about fecal transplants for antibiotic-resistant C. diff infections? What do you think about antibiotic overuse? Share your thoughts in the comments.

***

Additional Reading: