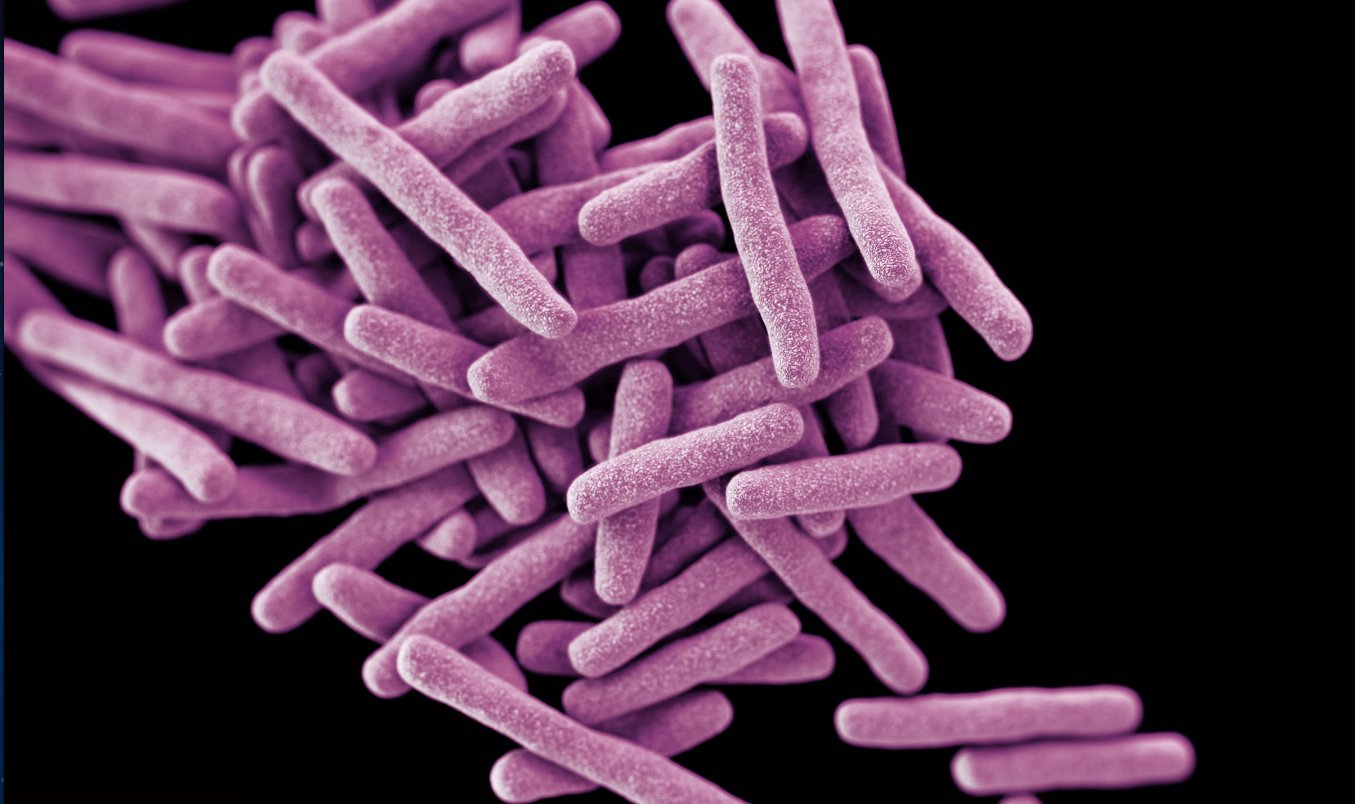

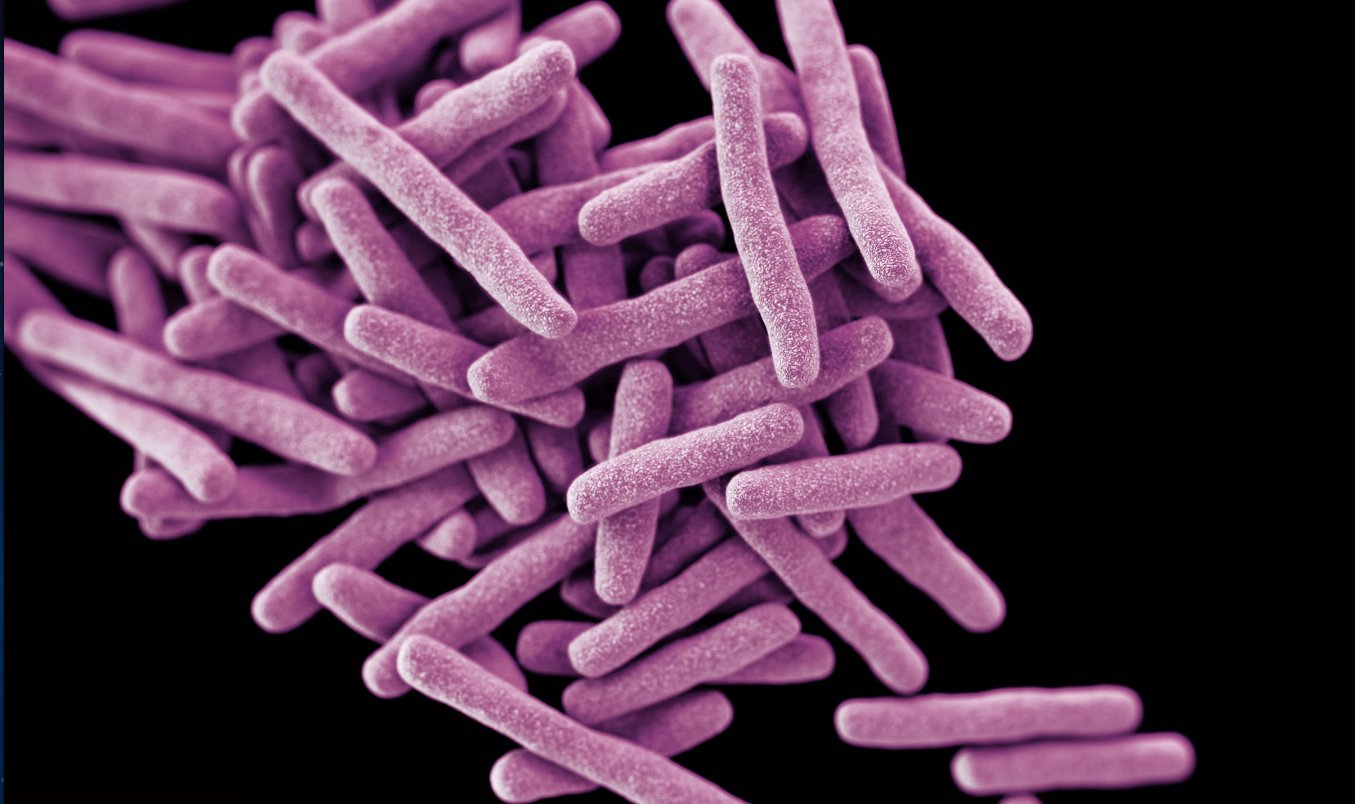

Measles and Ebola have dominated the headlines in recent weeks, but there are plenty of other infectious diseases lurking among us. One is tuberculosis, which, in various times through its long history, was also known as the captain of death, the white plague, and consumption. In just the past couple of weeks tuberculosis struck a high school student in Sacramento, nine people—including a teacher at a Pre-K through eight grade school—in Vermont, and a student at a Washington DC community college. Around 10,000 cases occur in the United States each year.

Tomorrow, PBS’s American Experience will air a documentary on the history of tuberculosis in America. I watched an advance copy a few days ago and highly recommend it to folks who like to learn how infectious disease shapes both culture and society (there’s a lot of neat science, too, including early antibiotic discovery).

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, not long after scientists discovered the bacterium that causes TB, the US launched the first big public health campaign in the country. People were encouraged to use Kleenex and not to spit, while fashion shifted toward shorter hemlines for women and clean-shaven faces for men to avoid sweeping up and spreading the pathogen.

Most interesting for me, however, was the way public health officials treated TB patients. Government officials forced people who were infected into institutions or camps. This was particularly the case with working class immigrants, while the rich were left to treat their families as they saw fit.

“It’s an area of public health practice where, increasingly, the need of the community to be protected from the illness starts to trump the individual rights of the patient,” says historian Nancy Tomes in the documentary. “When people say ‘I don’t want to be taken away,’ their right to resist that is overridden in the name of public health.”

This public health versus private rights discussion is especially striking in light of the current measles outbreak. With our measles problem, though, we may have too much individual choice, particularly in states like California where people can forgo vaccines based on personal beliefs. If too many opt out, it ultimately puts the rest of society at risk. This may change: lawmakers in California are trying to tighten vaccine exemptions in response to the outbreak.

Of course, tuberculosis isn’t truly a forgotten plague—it may not be dominating headlines like measles, but a third of the world’s population is infected with the bacterium and 1.5 million died from it in 2013 alone. Thanks to resistant strains, that problem may only get worse.

To learn more, check out The Forgotten Plague tomorrow night at 9 p.m. Eastern on your local PBS listing.