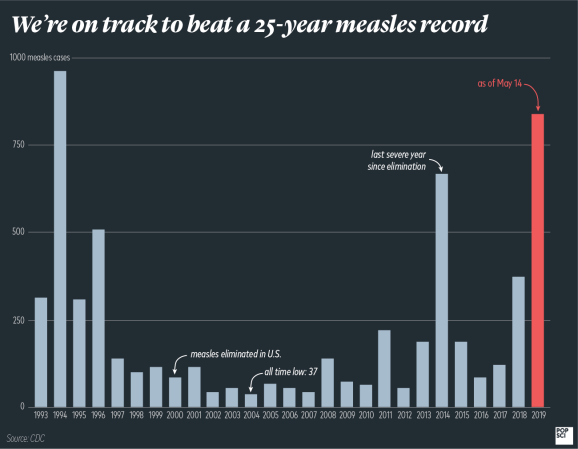

The U.S. just broke a 25-year-long record. We now have 981 measles cases in 2019, topping 1994’s 963—and it’s only June. But the bittersweet truth is that we’re unlikely to break any more contemporary records, if only because the the early ’90s were absolutely historic for measles.

Measles had been relatively dormant since the 1970s, since the vaccine was first introduced on a mass scale in the previous decade, but it came back roaring toward the end of the millennium. In 1989, the U.S. saw 18,193 cases in a series of huge outbreaks that spilled into 1990, when there were an astonishing 17,786 cases. All told, 132 people died. The outbreaks were so severe that it prompted health officials to start mandating a second dose of the MMR vaccine. It also highlighted an ongoing problem we’re not paying enough attention to: lack of access to the vaccine.

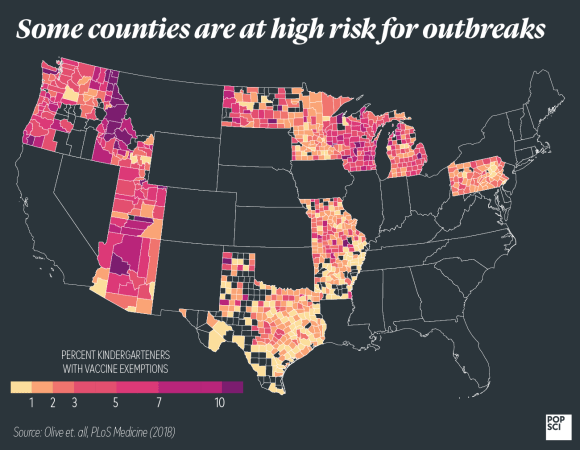

The outbreaks in the ’90s mostly involved kids from racial or ethnic minorities living in dense urban areas. They were from families who, statistically, had less access to regular, affordable vaccinations. Unfortunately, that’s still true today; Blacks and Asian Americans get measles at higher rates than do white, non-Hispanic people. And though we think of our modern outbreaks as being limited to parents who refuse to vaccinate, there’s also evidence that more children go unvaccinated without ever getting formal exemptions. The medical director for immunizations at the Arkansas Department of Health told the AP that, at least in her state, access remains a crucial issue. Most kids in Arkansas rely on Medicaid and live in areas without convenient pharmacies or doctor’s offices where they could easily get vaccinated. A CDC report even showed that most states currently below the 95 percent herd immunity threshold could achieve that rate without ever convincing an anti-vax parent—they’d just need to vaccinate all the kids who aren’t immunized and don’t have an exemption.

Perhaps more importantly, we may forget that ever since we eliminated measles from the U.S., all of our cases here are the result of importation. And though that may not seem like our problem, it actually is. A 2013 report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee noted that “recent threats from infectious diseases such as pandemic influenza or importation of VPDs [vaccine preventable diseases] such as measles highlight the fact that U.S. health is intricately linked to global health.” Historically, many of the American outbreaks we’ve seen in the 21st century have come from just a handful of countries like the Philippines, where there are large, regular outbreaks. It only takes one person to bring the virus into an otherwise measles-free zone.

That makes measles in the rest of the world a problem for us. “Our world is increasingly interconnected,” says Katrina Kretsinger, an immunization expert at the World Health Organization. “Even in countries and regions with quite high vaccination rates, pockets [of low-vaccination rates] tend to cluster together. And because measles is so infectious, it will find these pockets.” The WHO identified the anti-vaccination movement as a global threat, but Kretsinger notes that worldwide, the main reason measles immunization rates are low is simply because of insufficiently robust health systems.

It’s not exactly easy to solve those problems, because the barriers to vaccine access vary so much by region. But as we’ve progressively increased vaccination rates, it’s also requiring increasing commitment to continue moving forward. “It costs progressively more with each increment in the vaccination rate,” Kretsinger explains. “It costs more to reach that child because they’re in a conflict area, or because they’re in a hard-to-reach area.”

Eliminating or eradicating measles requires a sustained, global effort. It starts at home, with increasing access to affordable, convenient vaccines for everyone, but it doesn’t end there. A 2014 perspective piece in the New England Journal of Medicine noted that “In the end, we can best protect our population against measles by ensuring that people eligible for vaccination are vaccinated and by supporting global efforts to go on the offensive against this major cause of the global disease burden.” After all, the authors write, “vaccines don’t save lives—vaccinations do.”