In space, no one can hear a probe smash into an asteroid—but that’s just what happened in September, when NASA’s successful DART experiment proved that it’s possible to reroute a space rock by crashing into it on purpose. And that wasn’t even the most important event to materialize in space this year—more on the James Webb Space Telescope in a moment. Back on Earth, innovation also reached new heights in the aviation industry, as a unique electric airplane took off, as did a Black Hawk helicopter that can fly itself.

Looking for the complete list of 100 winners? Check it out here.

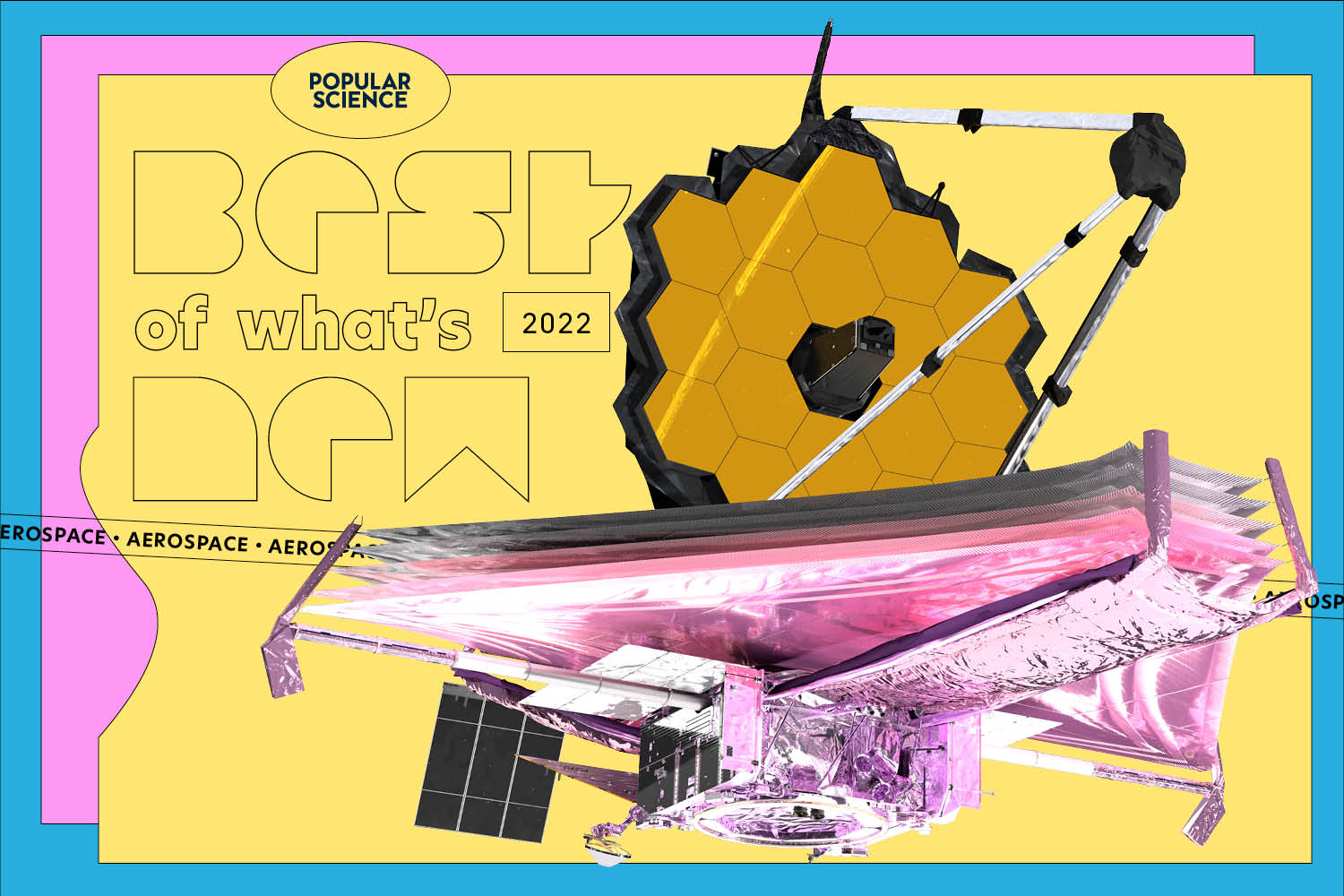

Innovation of the Year

The James Webb Space Telescope by NASA: A game-changing new instrument to see the cosmos

Once a generation, an astronomical tool arrives that surpasses everything that came before it. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is just such a creation. After more than two decades and $9.7 billion in the making, JWST launched on December 25, 2021. Since February of this year, when it first started imaging—employing a mirror and aperture nearly three times larger in radius than its predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope—JWST’s vibrant images have captured the attention of the world.

The JWST can see deep into fields of forming stars. It can peer 13 billion years back in time at ancient galaxies, still in their nursery. It can peek at exoplanets, seeing them directly where astronomers would have once had to reconstruct meager traces of their existence. It can teach us about how those stars and galaxies came together from primordial matter, something Hubble could only glimpse.

While Hubble circles in low Earth orbit, JWST instead sits hundreds of thousands of miles farther away, in Earth’s shadow. It will never see sunlight. There, protected even further by a multi-layer sunshield thinner than a human fingernail, the telescope chills at -370 degrees F, where JWST’s infrared sight works best. Its home is a fascinating location called L2, one of several points where the sun and Earth’s gravities balance each other out.

All this might just be JWST’s prologue. Since the telescope used less fuel than initially anticipated when reaching its perch, the instrument might have enough to last well past its anticipated 10-year-long window. We can’t wait to see what else it dazzles us with.

Parallel Reality by Delta: A screen customized for you

You’ve probably found yourself running through an airport at some point, squinting up at a screen filled with rows of flight information. A futuristic new offering from Delta and a startup called Misapplied Sciences aims to change that. At Detroit Metro Airport, an installation can show travelers customized information for their flight. A scan of your boarding pass in McNamara Terminal is one way to tell the system who you are. Then, when you look at the overhead screen, you see that it displays only personalized data about your journey, like which gate you need to find. The tech behind the system works because the pixels in the display itself can shine in one of 18,000 directions, meaning many different people can see distinct information while looking at the same screen at the same time.

Electronic bag tags by Alaska Airlines: The last tag you’ll need (for one airline)

Believe it or not, some travelers do still check bags, and a new offering from this Seattle-based airline aims to make that process easier. Flyers who can get an electronic bag tag from Alaska Airlines (at first, 2,500 members of their frequent flier plan will get them, and in 2023 they’ll be available to buy) can use their mobile phone to create the appropriate luggage tag on this device’s e-ink display while at home, up to 24 hours before a flight. The 5-inch-long tag itself gets the power it needs to generate the information on the screen from your phone, thanks to an NFC connection. After the traveler has done this step at home, they just need to drop the tagged bag off in the right place at the airport, avoiding the line to get a tag.

Alice by Eviation: A totally electric commuter airplane

The aviation industry is a major producer of carbon emissions. One way to try to solve that problem is to run aircraft on electric power, utilizing them just for short hops. That’s what Eviation aims to do with a plane called Alice: 8,000 pounds of batteries in the belly of this commuter aircraft give its two motors the power it needs to fly. In fact, it made its first flight in September, a scant but successful eight minutes in the air. Someday, as battery tech improves, the company hopes that it can carry nine passengers for distances of 200 miles or so.

OPV Black Hawk by Sikorsky: A military helicopter that flies itself

Two pilots sit up front at the controls of the Army’s Black Hawk helicopters, but what if that number could be zero for missions that are especially hazardous? That’s exactly what a modified UH-60 helicopter can do, a product of a DARPA program called ALIAS, which stands for Aircrew Labor In-Cockpit Automation System. The self-flying whirlybird made its first flights with zero occupants on board in February, and in October, it took flight again, even carrying a 2,600-pound load beneath it. The technology comes from helicopter-maker Sikorsky, and allows the modified UH-60 to be flown by two pilots, one pilot, or zero. The idea is that this type of autonomy can help in several ways: to assist the one or two humans at the controls, or as a way for an uninhabited helicopter to execute tasks like flying somewhere dangerous to deliver supplies without putting any people on board at risk.

Detect and Avoid by Zipline: Drones that can listen for in-flight obstacles

As drones and other small aircraft continue to fill the skies, all parties involved have an interest in avoiding collisions. But figuring out the best way for a drone to detect potential obstacles isn’t an easy problem to solve, especially since there are no pilots on board to keep their eyes out and weight is at a premium. Drone delivery company Zipline has turned to using sound, not sight, to solve this conundrum. Eight microphones on the drone’s wing listen for traffic like an approaching small plane, and can preemptively change the UAV’s route to get out of the way before it arrives. An onboard GPU and AI help with the task, too. While the company is still waiting for regulatory approval to totally switch the system on, the technique represents a solid approach to an important issue.

DART by NASA and Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory: Smashing into an asteroid, for good

Earthlings who look at the sky in fear that a space rock might tumble down and devastate our world can now breathe a sigh of relief. On September 26, a 1,100-pound spacecraft streaked into a roughly 525-foot-diameter asteroid, Dimorphos, intentionally crashing into it at over 14,000 mph. NASA confirmed on October 11 that the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART)’s impact altered Dimorphos’s orbit around its companion asteroid, Didymos, even more than anticipated. Thanks to DART, humans have redirected an asteroid for the first time. The dramatic experiment gives astronomers hope that perhaps we could do it again to avert an apocalypse.

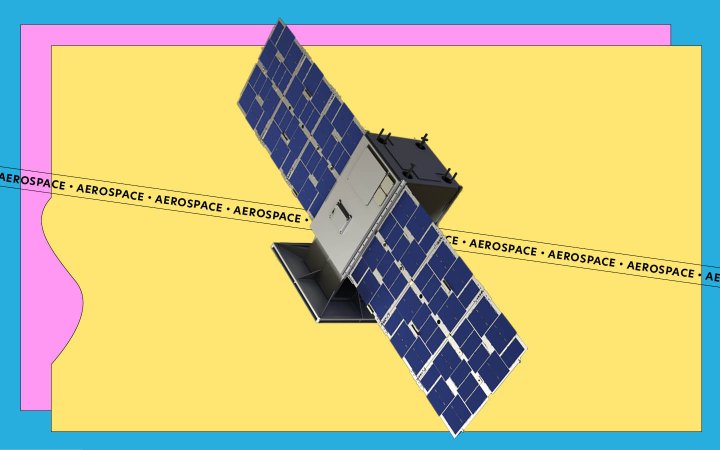

CAPSTONE by Advanced Space: A small vessel on a big journey

Some lunar craft fill up whole rooms. On the other hand, there’s CAPSTONE, a satellite that can fit on a desk. Despite control issues, CAPSTONE—which launched on June 28—triumphantly entered lunar orbit on November 13. This small traveler is a CubeSat, an affordable design of mini-satellite that’s helped make space accessible to universities, small companies, and countries without major space programs. Hundreds of CubeSats now populate the Earth’s orbit, and although some have hitched rides to Mars, none have made the trip to the moon under their own power—until CAPSTONE. More low-cost lunar flights, its creators hope, may follow.

The LSST Camera by SLAC/Vera C. Rubin Observatory: A 3,200-megapixel camera

Very soon, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in the high desert of Northern Chile will provide astronomers with what will be nearly a live-feed view of the southern hemisphere’s sky. To do that, it will rely on the world’s largest camera—with a lens 5 feet across and matching shutters, it will be capable of taking images that are an astounding 3,200 megapixels. The camera’s crafters are currently placing the finishing touches on it, but their impressive engineering feats aren’t done yet: In May 2023, the camera will fly down to Chile in a Boeing 747, before traveling by truck to its final destination.

The Event Horizon Telescope by the EHT Collaboration: Seeing the black hole in the Milky Way’s center

Just a few decades ago, Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy’s heart, was a hazy concept. Now, thanks to the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), we have a blurry image of it—or, since a black hole doesn’t let out light, of its surrounding accretion disc. The EHT is actually a global network of radio telescopes stretching from Germany to Hawaii, and from Chile to the South Pole. EHT released the image in May, following years of painstaking reconstruction by over 300 scientists, who learned much about the black hole’s inner workings in the process. This is EHT’s second black hole image, following its 2019 portrait of a behemoth in the galaxy M87.

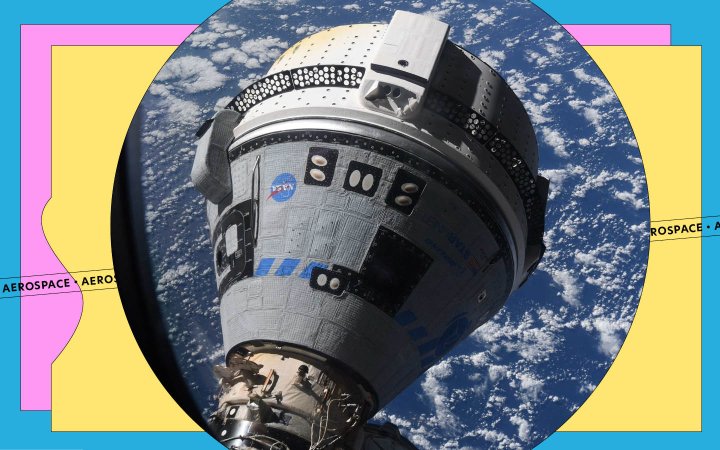

Starliner by Boeing: A new way of getting to the ISS

After years of budget issues, technical delays, and testing failures, Boeing’s much-awaited Starliner crew capsule finally took to the skies and made it to its destination. An uncrewed test launch in May successfully departed Florida, docked at the International Space Station (ISS), and landed back on Earth. Now, Boeing and NASA are preparing for Starliner’s first crewed test, set to launch sometime in 2023. When that happens, Starliner will take its place alongside SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, and NASA will have more than one option to get astronauts into orbit. There are a few differences between the two: Where Crew Dragon splashes down in the sea, Starliner touches down on land, making it easier to recover. And, where Crew Dragon was designed to launch on SpaceX’s own Falcon 9 rockets, Starliner is more flexible.