NASA has set the ambitious (some might say aspirational) goal of sending a crew to the moon in 2024, but this time it doesn’t want to go alone. On Monday, the agency announced that five new companies will be joining its lunar support posse: SpaceX, Blue Origin, Sierra Nevada Corp., Ceres Robotics and Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems, Inc.

And they’ll come in handy. Doing all the science, all the scouting and mapping, and building all the necessary rockets, vehicles, and infrastructure to explore the moon is a lot of work. As NASA continues with its Artemis program to return humans to the moon, it will be relying on help from the Commercial Lunar Payload Service (CLPS) initiative, which establishes a roster of companies that can bid on missions to take NASA hardware to the moon. If all goes well, these five plus nine other collaborators named last year will compete for contracts collectively worth up to 2.6 billion dollars over the next decade, and the lunar surface will experience traffic the likes of which it hasn’t seen since the Apollo program.

“What I would like to do is build up a cadence of at least two [lunar missions] per year,” said Steve Clarke, the deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate during a conference call on Monday.

The quintet of companies runs the gamut in terms of size and space experience. On the heavy lifting end, SpaceX will offer its reusable Starship platform for shipping up to 110 tons of material to the moon—roughly the weight of two military tanks. The company unveiled a simple prototype of the ship in September. Though it has not yet built the rocket needed to launch it, the company expects it to be functional within a few years. “We are aiming to be able to drop Starship on the lunar surface in 2022,” SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell said on the call.

For midsize loads, NASA may call on Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lander, which has been in development for a few years. The Blue Moon will reportedly be able to handle a few tons of heft, and will also rely on fuel cells (as opposed to solar power) to survive the long lunar night.

The Sierra Nevada Corporation will be developing a trio of delivery vehicles based on technologies derived from current satellite hardware and the Dream Chaser, a crewed spacecraft under development since 2004.

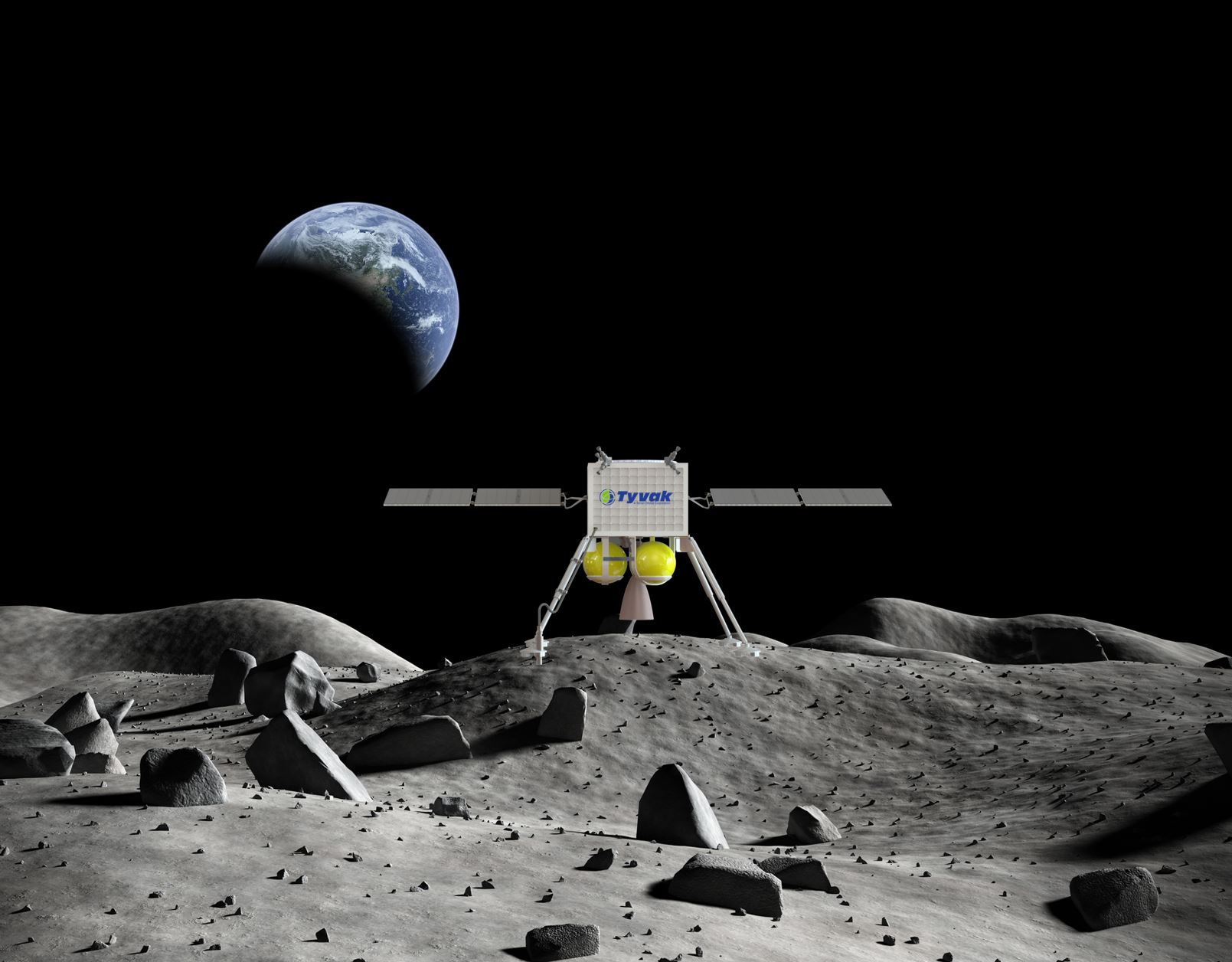

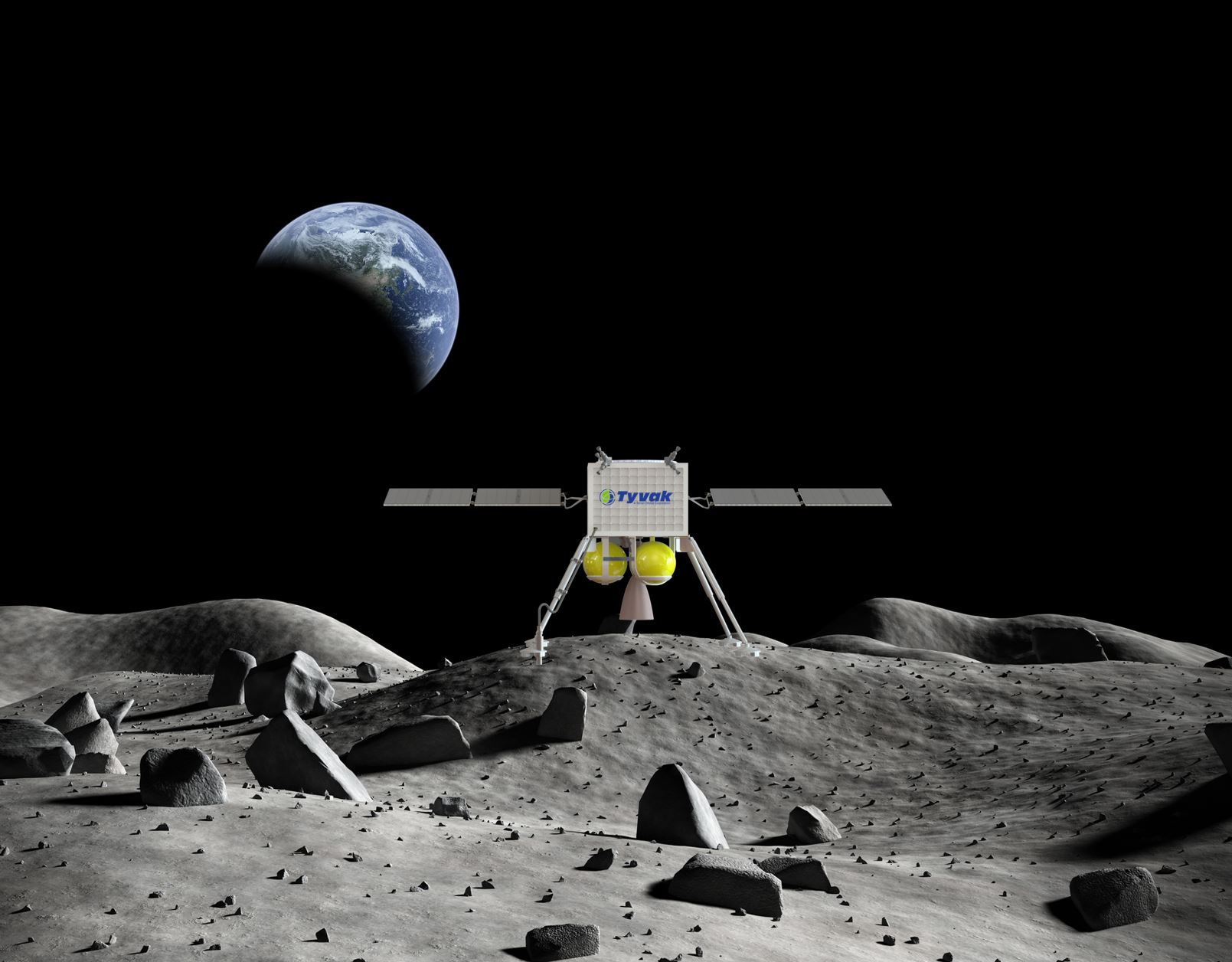

NASA also selected two relative newcomers, Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems and rover developer Ceres Robotics. In total the five companies, chosen from eight applications received after a call for proposals in July, join nine other companies previously named in 2018 as CLPS providers.

Now, when NASA wants to send a science or exploration mission to the moon, such as the upcoming ice-prospecting VIPER rover in late 2022, the CLPS pool of partners will theoretically serve as something like a lunar version of Uber. Rather than arranging the whole ride from scratch, NASA will describe where it wants to go and the instruments or equipment it would like to bring. Then the private partners will then submit bids and compete for the privilege of getting the hardware from terra firma all the way to the moon’s dusty surface. “These are not NASA missions. These are CLPS provider missions,” said Clarke. “We are operating along with [the providers] and buying a ride.”

When each of the fourteen providers will be capable of delivering such a ride remains to be seen, but two companies from the previous group, Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines, have already won contracts worth nearly 80 million dollars each to land missions in 2021. NASA originally awarded a third contract for a 2020 landing, but the company has since cancelled the agreement.

The agency will have plenty of work for any companies that are able to step up, with a dozen science packages and technology demonstrations already ready or nearly ready to go.

In addition to bringing NASA’s breakneck lunar timeline one step closer to reality, the billions of dollars invested in CLPS will also, the agency hopes, have a build-it-and-they-will-come halo effect. Once a few companies are regularly delivering payloads to the lunar surface, the thinking goes, those services could attract others interested in paying to send equipment into space, opening up a lasting shipping lane between the Earth and the moon.

“We’re on the precipice,” Clarke said, “of seeing the commercial services expand and flourish with not just NASA as a customer but lots of other customers. I think this is a catalyst here and we’re going to see this grow more and more over the next five years.”