A deep dive on the evolution of COVID and its variants

The reason we know so much about how SARS-CoV-2 works is because virologists have been tracking its mutations in real time. What they've seen has floored them.

When SARS-CoV-2 was first isolated in January 2020, researchers who studied viral genetics said it would mutate at some point. With millions of chances to replicate and adapt, mutations were an inevitability. But at first, many scientists thought the process would play out over years or longer. Instead, the past 24 months have been shaped by a procession of new variants, each with its own ability to cause disease.

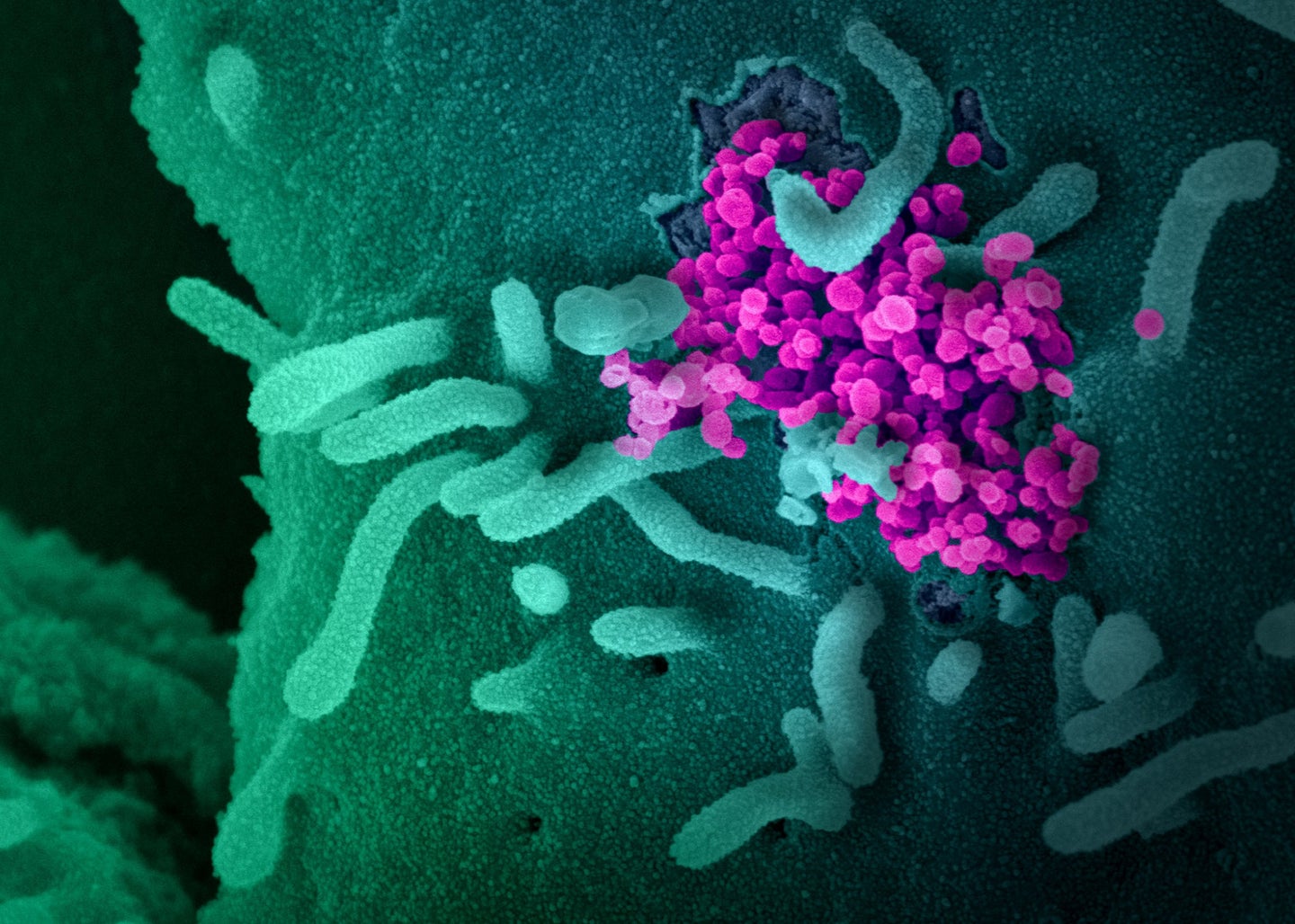

Over the last two years, a flood of imaging, genetic sequencing, and experimenting with everything from modified viral particles to disembodied spike proteins has allowed scientists to explain how this pathogen and its variants killed more than 6 million people and infected millions more.

[Related: Why it’s so hard to make quick, accurate estimates on new COVID variants]

The infectiousness and deadliness of SARS-CoV-2 depends on countless factors. To be successful, the virus has to grab onto host cells, reproduce inside, and then make a quick exit. It also has to adapt to different kinds of cells, from the lungs to the heart, and survive in tiny droplets in the air so it can spread from person to person.

Mutations affect all of those traits. But for the moment, the clearest window into the forces shaping the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 comes from studying the moment a single virus enters a human cell. Understanding that process can give researchers hints to how it might change next.

How the coronavirus attacks

A SARS particle is shaped like a chestnut seed: It has a packet of RNA and reproductive materials inside a thin shell covered with spike proteins. Those extensions pulse and sway, looking for a compatible protein on the surface of human cells to latch onto. Because the spikes are SARS-CoV-2’s main tool for invading cells, they’re also the primary target of antibodies—a person’s first line of defense against infections.

The tips on the spikes aren’t static, either. They each have a suction cup-like attachment, called the receptor binding domain (RBD), that flips up and down. The virus can only invade a cell when the RBD is flipped up, but that also leaves it open for attacks by the host’s immune system. Shang-Te Danny Hsu, a structural biologist at Academia Sinica in Taiwan, compares the RBD to a submarine’s periscope. “SARS-CoV-2 will lift the periscope to find a target, but at the same time, the antibody will recognize it,” he says.

Once a spike latches onto a human cell, the virus needs to fuse its body with the host and dump its genetic contents inside. All the machinery needed for that sits locked behind the RBD, in a piece of the spike called “S2.” To release it, the virus relies on a specific human protein, TMPRSS2 (“tempress”), to act like a pair of scissors. When tempress comes across a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein attached to a human cell, it snips off the RBD, exposing a spring-loaded system that sucks the virus and cell together. (Biologists still aren’t exactly sure what tempress does in humans, besides its role in COVID and other diseases.) Tempress coats human cells in the lungs, heart, liver, kidney, and gut, which might explain the range of symptoms caused by COVID-19.

There are three central factors that shape the virus’s journey through that process. First is how often spikes send up their “periscopes;” second is how tightly the RBD latches to human cells; and third is how well the spike can dodge human antibodies. Those mechanisms are determined by 1,273 amino acids, which fold up to form the body of the spike protein. A tiny change of as much as a single missing molecule can reshape the virus’s weaponry in surprising ways.

D614G mutant (“DOUG”)

First identified: February 2020 in Europe

Why it matters

D614G isn’t technically a variant—it’s just a single mutation that appeared in many of the first global COVID outbreaks. But it was the first mutation that tipped virologists off to the speed that SARS-CoV-2 could adapt. In early research posted online in April 2020, a team led by scientists from Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico determined the anomaly made the virus more infectious.

How it works

The mutation sits near the middle of the spike protein, and makes each individual receptor binding domain more likely to flip up to bind to human cells. How often coronavirus spikes are open seems to be related to the deadliness of the disease, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear. Modeling by Maxwell Zimmerman, a computational biologist at Washington University in St. Louis, found that SARS-CoV-2 is more aggressive in extending its RBDs than mild human coronaviruses, but less so than SARS-1, which killed 10 percent of people it infected.

But what makes the mutation “weird and unique” is that it appears to set the stage for other variants, says Kyle Wolf, a biophysicist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. SARS-CoV-2 infects cells faster when it has more RBDs flipped up—but that also makes its spikes more likely to fall apart before they find their target. A virus with DOUG appears to be more stable: When its RBDs up, they wedge together, holding the spike proteins together until it finds a host, Wolf explains. The mutation could be required for other variants, which opened the spike even further, but needed a way to stabilize the package, says Sophie Gobeil, a structural biologist at Duke University.

Alpha variant

First detected: September 2020 in the UK

Why it matters

This was one of three strains that emerged in quick succession in the first year of the pandemic. All of them showed different but overlapping sets of mutations, which researchers believe could have arisen from prolonged infections in people who were immunocompromised. Alpha spread about 50 percent faster than the original virus, and was even more infectious than the DOUG mutant.

Further research found that Alpha had signs of antibody evasion, which gave it an edge in spreading in a population that has already experienced an outbreak. It was also around 73 percent more likely to kill unvaccinated people than prior strains.

How it works

Lab experiments showed that the variant was better at grabbing onto cells and at fighting off antibodies. Many of those changes had to do with mutations on Alpha’s RBD. One of the bigger mutations boxes out antibodies while also fitting extremely tightly into the binding site with the host cell, Gobeil says. Other receptor binding domain mutations lock down the virus against additional antibodies.

Alpha’s mutations also made it a more efficient invader. The variant lost two amino acids that sit deeper in the spike protein. Without them, the RBD flips up more often, which makes it easier to grab onto cells and slip inside quickly.

Those aggressive qualities also seem to play a role in later stages of the infection. After SARS-CoV-2 storms a human cell, it can cover the outer lining of its new vessel in spike proteins. Then, like a pirate crew steering a stolen ship, the infected cell grapples in and fuses with other cells, allowing the virus to hijack multiple hosts without leaving its original refuge. Alpha appears exceptionally good at that process, creating globs of infected cells that probably cause severe lung damage.

Tools to ID COVID variants

Cryo-EM

To see how SARS-CoV-2 fits together on the molecular level, and how it interacts with human cells, structural are tapping a powerful imaging method called cryo-electron microscopy, or cryo-EM.

The process is deceptively simple. Scientists place tens or hundreds of thousands of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on a thin slide, and then freeze them to get a clearer picture. The cryo-EM then shoots electrons through the slide to cast a silhouette of each individual protein. Each shadow is just a blob, but with thousands of them, algorithms can stitch together into a 3D image that captures the near-atomic-level differences between the shapes of variants.

Image by NIAID

Beta and Gamma variants

First detected: May 2020 and November 2020 in South Africa and Brazil, respectively

Why they matter

The variants didn’t go global in the same way as Alpha, but Hsu, the biologist in Taiwan, thinks that might have been a matter of circumstance. If they’d emerged in a country where air travel was popular, like the UK, he says they could have been just as problematic.

How they work

Both variants have a set of mutations that allows them to shrug off antibodies that would otherwise clog up their binding machinery. This is, according to coronavirus researcher Thomas Gallagher, a professor at Loyola University Chicago, “the most obvious and straightforward way to evade [antibodies].”

Most strikingly, one mutation called E484K changes the shape of a “hook” structure on the side of the spike protein that some antibodies latch onto. In the original virus, the hook was present half the time, Gobeil from Duke University says. But with the mutation, the hook falls apart like a pile of spaghetti, so there’s nowhere for antibodies to bind.

Delta variant

First detected: February 2021 in India

Why it matters

Although it wasn’t identified for a few months, the Delta variant emerged during India’s catastrophic COVID wave in fall of 2020 before creeping across the world. It’s two or three times more infectious than the first strain of SARS-CoV-2 (the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have compared it to chickenpox), and was the first signal that a SARS-CoV-2 variant could be infectious enough to spread widely among vaccinated individuals, says Ravindra Gupta, a microbiologist at the University of Cambridge. But further analysis showed that it was also good at evading antibodies, both in people who were previously infected and in those who were jabbed.

As cases multiplied, it quickly became apparent that those with vaccines were more likely to catch and spread Delta than previous variants, although they were still protected from getting sick. But for the unvaccinated, it was several times more likely to cause severe illness and death. When it finally arrived in the US in the summer of 2021, the CDC reevaluated its vaccine-dependent COVID strategy, writing that “the war has changed.”

How it works

“I think it basically just picked up on Alpha, and got better at doing [the same thing],” Gobeil says. Delta is a virus that is extremely ready to bind: Mutations on the tip of the receptor binding domain allow it to latch onto human cells tightly, and its RBDs to flip up more. In the first variants, “you saw one RBD sticking out, like it’s reaching for a receptor,” says Jeremy Kamil, a virologist at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport. “By the time we got to Delta, structural biologists were seeing spikes with two or three up.”

That could partially be attributed to mutations far down the spike protein that kept the receptor binding domains from sticking together when they closed. Those same mutations seem to block antibodies from latching on to a particularly attractive spot far from the RBD. And like Alpha, the ready-to-open nature of Delta’s spikes lets it spread from cell to cell directly. “It was super good at inducing fusion between two cells,” says Gupta.

But what made Delta even more dangerous was its ability to juice up its offspring. In theory, all newly-minted SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins can get an extra snip from a human protein (different from tempress) while exiting a host cell. The second perforation makes the spike more flexible, making it easier for the pathogen to invade other cells. In the original virus, that maneuver was seen in about 10 percent of infections. In Delta, it was 75 percent.

Tools to ID COVID variants

Genomic sequencing

Over the last 20 years, the price of sequencing a viral genome has fallen from more than $1,000 to between $50 and $250. This has allowed labs across the world to sequence individual COVID samples in mere weeks.

GISAID, the most widely used database of SARS-CoV-2 sequences, currently holds more than 9 million individual viral genomes, allowing researchers to track mutations almost as soon as they emerge. Close to a third of those samples have come from the US.

Illustration via Nextstrain. Sequence data from GISAID. Full author information available here.

Omicron variant

First detected: November 2021 in South Africa and Botswana

Why it matters

Last fall, virologists cautiously predicted that Delta would be the model for future COVID strains. And indeed, from August 2021 to late November 2021, almost every single US COVID case was linked to Delta or its subvariants, like Delta-plus.

Then Omicron hit. So far, it’s the most mutated SARS-CoV-2 variant, with 50 individual changes across its genome and 30 in the spike protein itself. It’s also among the most infectious respiratory viruses humans have encountered, period. Part of that is because it’s exceptionally good at dodging antibodies, so it can spread through vaccinated or previously recovered people (without causing critical illness in most cases).

In many parts of the world, Omicron has killed a smaller percentage of people it has infected, but it’s still not clear whether it’s an intrinsically less severe virus. In spite of that, the variant has devastated healthcare systems across the globe by the sheer speed of its spread—evidence that viral evolution can go in unexpected directions.

How it works

Omicron is familiar in that it has many of the same mutations that let Alpha, Beta, and Gamma dodge antibodies. But when it comes to infecting cells, it takes a completely different approach—one that could signal a shift in the evolution of the virus.

While the spikes on other COVID variants stick up multiple receptor binding domains at a time, Omicron’s tend to stay bunched together when folded down, only poking one up at a time. Gallagher from Loyola University Chicago says this might be a “less obvious” way of warding off antibodies, by hiding vulnerable spots.

On its face, that seems like it’d make it harder to infect cells, because the virus would have less of a chance to grab on to something without waving. But the folded-down spikes appear to survive better inside a host, and grab onto human cells extremely tightly when they do find a target.

And it favors a different route into the cell. Once an Omicron particle grabs a human receptor, instead of snipping itself open to climb inside the host, it continues to hang on for dear life. Eventually, the cell swallows it up in a “tasting” bubble called an endosome.

Typically, a cell digests the acidic contents of its endosomes. But Omicron seems to have adapted to survive the harsh conditions to enter the cell through the service door. That could go a long way in explaining why the variant takes hold in the nose and throat, rather than deep in the lungs. “It is really quite defective in some cells where Delta was really good,” says Gupta. (Lung cells, it turns out, have more of the cell-surface proteins that Delta relies on.)

That could be a clue that SARS-CoV-2 is evolving to become more like mild human coronaviruses, which also tend to stay folded up. “At the time of spillover, it was just transmitting in a population where nobody had antibodies,” and favoring open, Delta-like viruses that would rapidly spread among susceptible hosts, Wolf explains. In other words, Delta and its predecessors might have been more like the weeds that spring up after a forest fire when there’s lots of light and room, rather than the slow-growing trees that fill in later.

Still, it’s not as simple as saying that variants like Omicron are going to be less deadly moving forward. It’s plausible that future SARS-CoV-2 variants will look more like other, folded-up human coronaviruses over time, Kamil says, “but that doesn’t mean zero disease. The thing to be clear about is: We don’t know the timescales.”

[Related: The 5 phases of COVID’s endgame]

Humans have never knowingly watched a coronavirus pandemic play out. There could be many more waves of variants that look like Delta; Omicron could continue to threaten those with serious health conditions, much more so than the flu. “Immunity is likely to contain the disease more than viral evolution,” says Kamil. “I think the important lesson is, don’t wait for the virus to evolve—get vaccinated.”

As public health agencies move away from tracking individual COVID cases, it’ll become even more critical to predict which mutations might give SARS-CoV-2 an edge. Not only will it help officials spot worrisome variants faster—it will also help virologists gain more insight on what another pandemic could look like.

Correction (March 14, 2022): An earlier version of this story overstated the historical cost of sequencing a viral genome.