An influential new report uses contributions from over 100 professionals in space-related research and industry across the globe to plan for the next decade of space exploration—and they have set their sights on the planet Uranus and an icy moon of Saturn named Enceladus.

The report was published last week by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, which is an independent organization tasked with helping NASA and the National Science Foundation to assess the state of planetary science research and choose goals. A previous report led to two of NASA’s biggest missions of this decade.

Scientists would love to “visit every body in the solar system,” but there are finite resources, so the report helps direct money towards the projects that will offer the most bang for their buck, says Amy Simon, the vice chair of the report’s giant planet systems panel and a planetary scientist at NASA.

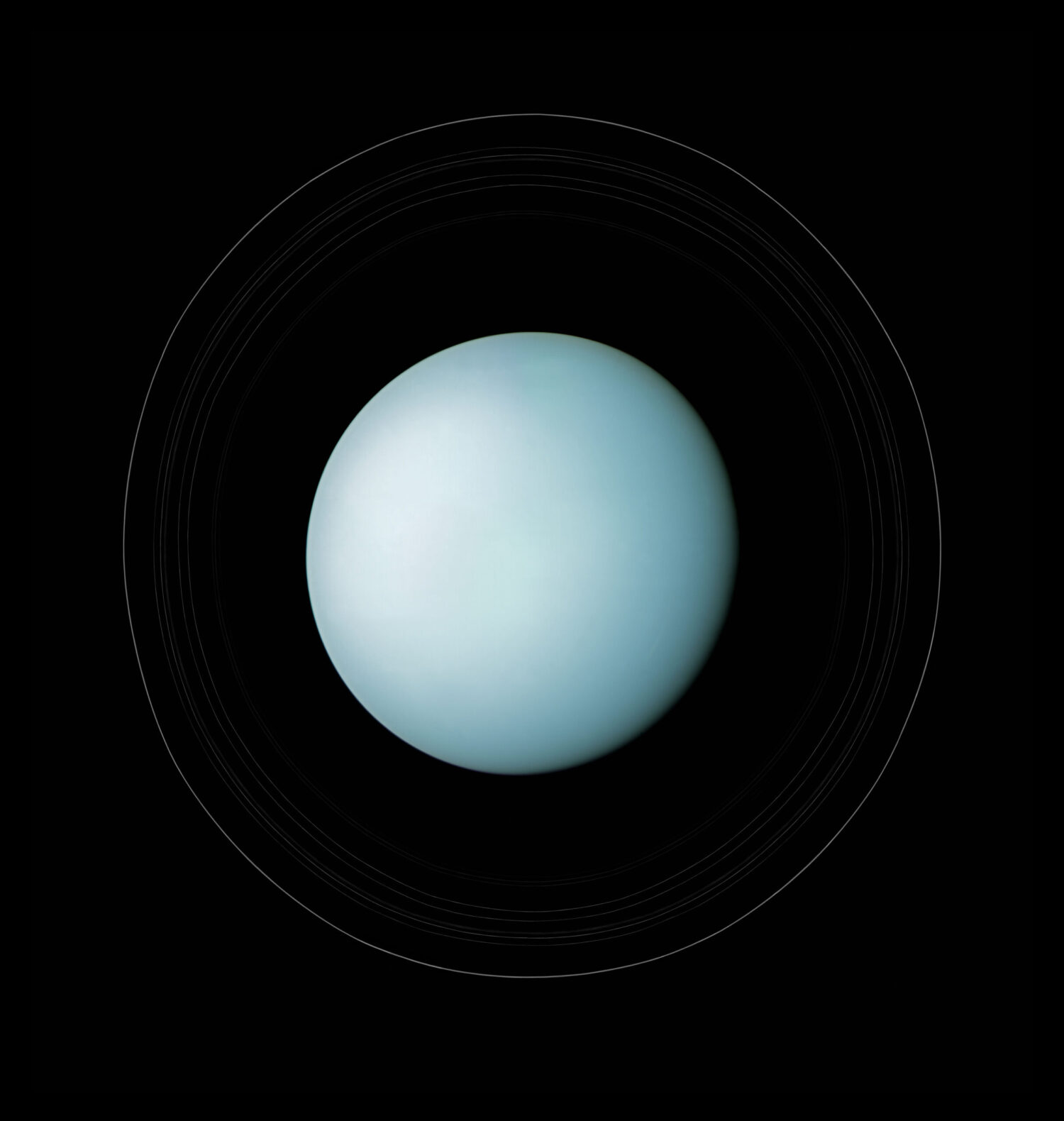

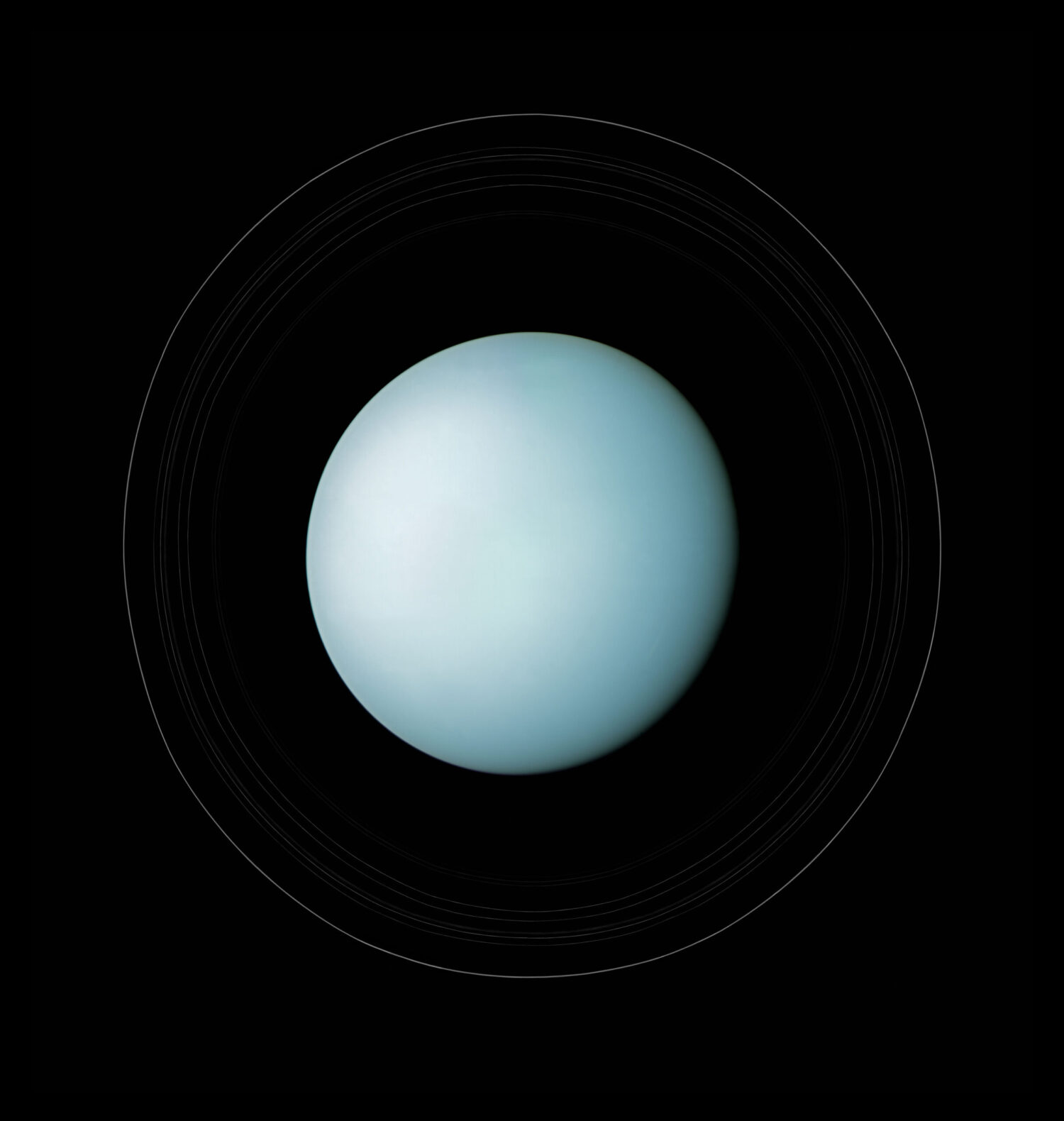

The last decadal survey, published 2011, recommended three “flagship” priorities: a sample return campaign to deliver Martian rocks to Earth, a major goal of the ongoing Perseverance rover project; a mission to the Jovian moon Europa, which became Europa Clipper; and a Uranus mission, which is yet to happen. Although the recommendations aren’t binding, NASA takes these reports seriously. Simon is “pretty optimistic” that a mission to Uranus, at least, will begin in the next decade.

This time, the 10-year report has “a renewed emphasis on astrobiology—looking for habitability and or existing life in the solar system,” Simon says, as well as a focus on exoplanets, which are worlds that exist outside our solar system.

The new survey had two top priorities: A flagship mission to explore Uranus and another to visit Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Both missions have been high priorities since the last survey, Simon says.

“Sending a flagship to Uranus makes a lot of sense” because Uranus and Neptune “are fairly unexplored worlds,” says Mark Marley, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona and director of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory who reviewed part of the early report and called it “clear-eyed.” Studying these worlds will help scientists understand both the formation of our solar system as well as an entire class of common exoplanets. Though some people are upset because, outside of the sample return mission, there isn’t much of a focus on future Mars missions, he says.

Congress, which decides NASA’s funding, puts a lot of weight in these decadal surveys, Marley says. Mission ideas might already be on the table, but the reports tell NASA in what order to pursue them.

Uranus and Neptune, the “ice giants” of the solar system, are among the least studied planets in our solar system. But exploring them in finer detail could help astronomers understand more about exoplanets—the ice giants share their mass, 10 to 15 times that of Earth, with the most common type of newly discovered exoplanets.

Uranus and Neptune are similar in their size, though Uranus has a colder subsurface than the other three gas giants, spins sideways, and has a system of moons that formed along with it. Neptune’s gravity, meanwhile, captured its moon Triton after the planet had formed, Simon says. Though Triton has earned researchers’ interest because it “could be an ocean world,” she says, the choice of which ice giant should be a higher scientific priority depends on who you ask. What’s not up for debate is that Neptune is about 50 percent farther from Earth, making it harder for a craft to reach and orbit around.

[Related: We’re finally figuring out how Uranus ended up on its side]

Astrobiologists are particularly interested in Enceladus, meanwhile, for its potential to be habitable to life.

Enceladus is an icy moon that’s roughly 300 miles in diameter and orbits around Saturn. The Cassini spacecraft first investigated Enceladus in 2005 and found evidence that it regularly spews plumes of water into space, suggesting there’s a liquid water ocean under the moon’s icy surface. Cassini flew through these plumes to measure their contents and found salty water with organic molecules, even though the orbiter wasn’t designed specifically for that task. Jupiter’s moon Europa likely also has a subsurface ocean, but Jupiter is very radioactive, which makes Saturn’s moon potentially a better bet for discovering life, Simon says.

The fact that Enceladus’s plumes are “spewing material all over the Saturn system” means that scientists have a way to study the contents of the planet’s subsurface with relative ease, Simon says. An orbiter could swoop through the plumes in space, rather than sending a robot to the moon to crack through the ice—which could be many miles thick.

The scope of new missions will depend on how much NASA’s budget grows in coming years and how expensive the mission to collect Perseverance’s Mars samples becomes, Marley says. But with decent funding, there’s a good chance that one or both missions come to fruition.