This past March, a sightseeing helicopter carrying five tourists crashed into the East River of New York City, taking all five lives with it. In the days and weeks that followed, the company that chartered the flight, FlyNYON, came under intense scrutiny. The media—from local news outlets to the national networks to press such as The New York Times, USA Today, and my own coverage in Wired and The Drive—fixated on a key safety shortcoming: The passengers had been inescapably tethered to the sinking chopper by the harnesses intended to secure them during the open-door, photography-oriented flight, turning what should have been a survivable water landing into a horrific tragedy.

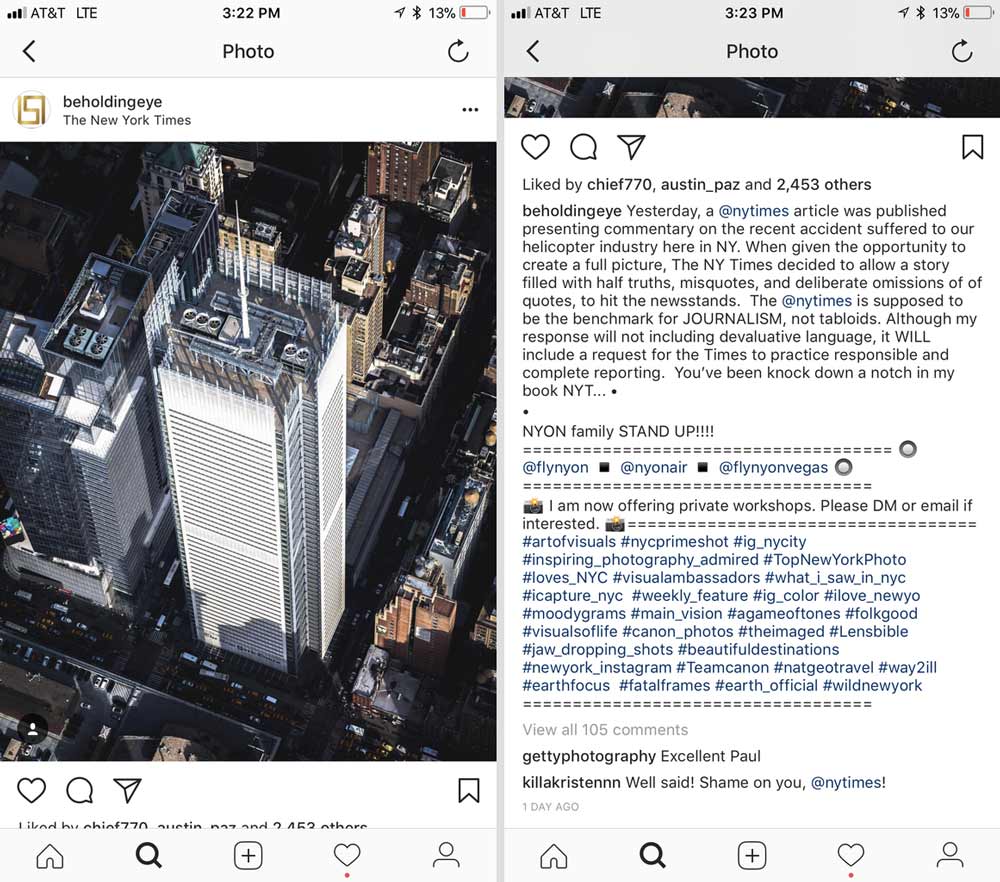

As the public descended on the company’s social media feeds—seeking information about the accident and often refunds on booked flights—something disturbing unfolded on Instagram. There, in the days and weeks that followed, FlyNYON’s paid influencers began unspooling a very different and potentially dangerous reality, all in the upbeat argot of a tone-deaf marketing squad. “Beautiful days ahead!” wrote Paul Seibert (@beholdingeye), a FlyNYON “Alpha” ambassador, to his 67,000 followers at the time. “Love my @flynyon fam” posted Matthew Pugliese (@mattpugs, 27,000 followers).

As the influencer group struggled to keep things upbeat, on FlyNYON’s channels and their own social feeds, tensions naturally escalated and the tone turned. Pointed and combative exchanges with the public began to pop up alongside the influencer’s boosterism and beauty shots. When one citizen poster urged the company’s followers to click over to a news report about the controversial safety harnesses that FlyNYON used during its open-door flights, “Ambassador” Craig Fruchtman (@craigsbeds, 93,000 followers), swept in with his keyboard set to neutralize: “They are the safest company you can fly with in the country,” wrote Fruchtman without any supporting evidence or facts. “There is no company that has as many safety protocols as they do… that’s a fact.”

Brand ambassadors are certainly entitled to support their corporate partners during crises. Whether its a celebrity hired in a sponsorship deal or a social media influencer with substantial followings, you’re gonna lick the hand that feeds you. The subtle charm, and influence, of these relationships is that they possess auras of informality. They’re meant to suggest that “Hey, we’re all friends here.” There’s often no mention of the mercenary—the merch, cash, and services that influencers pocket (or wear) in exchange for showing, mentioning, or endorsing a company’s products and services. “I actually drink this protein shake and you should, too.”

Influencer marketing, done right, can benefit all sides, including consumers hungry for new protein shakes. The problem is when consumers are fed misleading and ethically questionable posts. Some of those may even violate Federal Trade Commission guidelines, which require influencers and partner companies to explicitly reveal “material relationships.” The FTC says the same rules that apply to any advertising and sponsorship deals IRL also apply in cyber life.

And this is where FlyNYON’s brand ambassadors appear to have crossed the line. In the wake of the fatal crash, none of the ambassadors defending or endorsing the company appeared to identify themselves as FlyNYON’s paid partners in their posts or comments. That may happen a lot on social media with other seemingly organic posts and endorsements. But FlyNYON’s ambassadors—photographers with reasonably significant social media followings—took things further. They appeared to be actively encouraging followers to ignore safety concerns about their partner company. By doing so, they compromised not just advertising ethics, but also the lives of any followers who might have taken their endorsement to heart, should another incident involving the company have occurred.

Influencers Amok

Social media influencers still have the sheen of the hot new thing, but the wild-west landscape they have inhabited is fading fast, courtesy of those pesky FTC rules. The agency establishes standards for transparency in influencer marketing, just as it has done for radio, television, and print advertising dating back to 1980. That year, it published its first Guides for the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising. It updated those in 2009 to add examples of social media marketing, and again in 2015 and 2017 to address specific scenarios on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter, and other social channels.

Legally, all such marketing falls under Section 5 of the FTC Act, which prohibits unfair or deceptive commercial practices. “The law requires that those with a material connection to a company need to conspicuously disclose that connection,” says Jeffrey Brown, an attorney with the law firm Michael Best & Friedrich LLP, who specializes in brand/ambassador partnerships. “This enables the public to assess the credibility of a particular claim or endorsement. Moreover, the FTC takes the position that the brand ambassador can’t make a claim that the company couldn’t legally make. That is, claims must be truthful and not misleading. So a claim of superiority requires substantiation.”

Early last year, it became clear that online marketers and their partners were playing loose with the rules when the FTC publicly spanked 90 brands and influencers for not adequately disclosing their relationships. It then followed up in September with 21 of them who didn’t seem to have gotten the message. These included celebrities Amber Rose (endorsing Fashion Nova, Eyechic, and others), Akon (Ratel Geneve), Naomi Campbell (Globe-Trotter Luggage), Scott Disick (Pearly Whites Australia), Lindsay Lohan (Alexander Wang), and Vanessa Hudgens (My Little Pony). But it also netted dedicated influencers such as Tiona Fernan (Ovdbrand) and Rach Parcell (Nike, Gap Kids). All earn money through deals with clothing, food, alcohol, and spa brands, among many other product and service categories.

While the guidelines aren’t laws, they explain the FTC’s view of the law. According to the Commission, “if it believes someone has engaged in deceptive endorsement practices, it can file a complaint alleging a violation of Section 5 and seek an administrative cease and desist order, or a federal court injunction.” There are no fines associated with these violations, but the FTC will pursue the issue as much as it feels is appropriate, as in cases against Lord & Taylor, Warner Brothers, Machinima, and ADT. In September, the FTC settled the first-ever complaint against social media influencers, the YouTube personalities Trevor “TmarTN” Martin and Thomas “Syndicate” Cassell, both of whom had failed to properly disclose their paid relationships with the gambling site CSGO Lotto.

The FTC makes clear that both influencers and brands are responsible for knowing the guidelines and abiding by them: If you take sponsorship cash, you have to disclose it in every single paid post and paid comment. Those disclosures have to be explicit and prominent; simply tagging the company is a fail. So is using the company’s own jargon for a paid pundit, like FlyNYON’s “Alpha” designation. Ambassadors instead have to plainly describe the monetary relationship or include hashtags like #ad or #sponsored. Hashtags can’t be smuggled into strings of other hashtags, or ones that don’t show up until after the “more…” link.

So in the case of FlyNYON’s ambassadors—both the official “Alpha” designation and the less formal “Contributor”—it’s not enough to tag @FlyNYON or its affiliate account @NYONair in their bios. They should have, but didn’t, use terms like #sponsored, #ad, or #ambassador. They also didn’t clearly state their financial partnerships with the company. (One former FlyNYON influencer said the company’s partnerships ranged from paid ambassadorships to unpaid “contributor” roles that snagged complimentary or discounted flights in exchange for promotion.)

Michael Ostheimer, an attorney in the FTC’s Division of Advertising Practices, also said that even complete and proper disclosures in an influencer’s Instagram bio aren’t enough. They have to appear in the specific posts, too. “Generally, I would say most followers aren’t going to see every post from an influencer,” says Ostheimer. “So if somebody is an influencer and partnered with a company, they should disclose in every post that specifically endorses that company that there’s a material relationship.”

The FTC wouldn’t formally comment on the FlyNYON posts or whether it would take action in the case. A spokesman did concede that “it doesn’t look like they’re doing it right.” So looking at those accounts, post chopper-crash and in the midst of the company’s PR crisis, public followers wouldn’t have known who was touting FlyNYON’s safety record. They certainly couldn’t tell the posts came from surrogates who were paid to write flattering things about it.

Brand Loyalty

Whether the FTC will come down harder in posts involving life-safety issues is unclear. A media representative did, however, indicate that “deceptive claims that implicate serious health concerns” are “always a high priority for the Commission.” He cited a recent case against Aromaflage mosquito repellent that included the company’s co-owner and a relative writing 5-star Amazon reviews of the company’s products.

Of course, it’s one thing to post about loving a protein shake you never drink, and another to defend a company accused, in the wake of a fatal accident, of significant life-safety lapses, all without providing any supporting evidence. In a Fake News moment, FlyNYON ambassador Seibert (@beholdingeye) even went so far as to deny the company’s role in the accident. When a commenter responded that “five fellow photographers suffered and ultimately perished while in the hands of FLYON [sic],” Seibert shot back in typical online vitriol: “IT WAS NOT at the hands of FlyNYON. They unfortunately happened to be FlyNYON customers in a chartered helicopter. Your [sic] painting an incredibly vague picture with only one color and brush my friend.”

When reached for comment, Seibert said he didn’t realize he was potentially violating the FTC guidelines on disclosure. “I was unaware of my responsibility, and have updated my bio to reflect that relationship,” he responded in an email. “I am a recent hire as an employee of NYONAir. I would never encourage anyone to disregard any safety concerns, and don’t feel that any of my posts reflect otherwise.” Fruchtman, another FlyNYON ambassador, refused to address the same questions, and even accused this writer of posting a fake negative review of his mattress store online.

What these players should have done, say experts, is be more transparent, and post with a lot of caution. “It’s advantageous for companies to tell their story to news outlets and reporters covering the story,” says Terry Fahn, a senior executive at Sitrick and Company, a PR firm noted for crisis management work. “That means engaging directly in a professional, non-adversarial manner to convey your side of the story, instead of taking a combative role or attacking those covering the story. Be very considerate and thoughtful about what you say and how you say it.”

Brand ambassadors also shouldn’t be allowed to stir the pot on the brand’s behalf, says Fahn. That’s was Seibert seemed to do the day after The New York Times ran a story that suggested FlyNYON knew about significant safety risks before the crash. Seibert trolled the paper by posting an image of The New York Times building in Times Square (which has long since ceased to be its headquarters). In his post, Seibert described the Times piece as “filled with half truths, misquotes, and deliberate omissions of of [sic] quotes.” He not only didn’t offer examples or counter fact, he again did not identify himself as a paid ambassador. (FlyNYON’s own account lambasted the Times piece as “#fakenews” and the company sent a helicopter to hover menacingly above the Times building while live-streaming video of it on its Instagram account.)

FlyNYON possibly executed its own FTC violations by actively using its ambassadors in its post-crash social media strategy, posting their passionate testimonials without identifying them as paid partners. It’s unclear whether the company encouraged—or even instructed—its ambassadors to post in the fashion they did, and there’s no way to directly know because FlyNYON did not respond to requests for comment to this story. Doing so could be even more problematic, according to Brown, though nothing may actually come of it officially. “If we’re dealing with ‘astroturfing’—a PR campaign masquerading as genuine grassroots comments—that’s something that could get the attention of the FTC,” he says. “But with limited resources and competing priorities, I wouldn’t bet they’ll take action here.”

In the aftermath of the social media campaign, FlyNYON’s influencers worked to cover the tracks. Defensive and combative comments and posts relating to the accident have by now mostly been deleted by the ambassadors or by FlyNYON (some in the wake of negative public reaction to the defensiveness posturing, others immediately after individuals were contacted for this story). Similarly, some of the ambassadors mentioned in this story have since revised their Instagram bios to reflect the nature of their paid relationship to the company. They still don’t appear to be clarifying their relationships in captions or comments that endorse it.

Elsewhere, Brown notes that social media influencers in general are finally starting to pay attention to the rules as laid out by the FTC. But that may be due to a shift in social acceptance rather than a bear hug of transparency. “The #sponsored and #ad hashtag are no longer seen as jarring, and have become part of the social media fabric,” Brown says. Some influencers are even acknowledging there’s value—a “badge of honor”—in a formal, declared relationship with a prominent brand, he added.

Still, when a serious crisis does strike, it might be wise to follow the lead of some of the FlyNYON ambassadors who managed to stay out of the post-crash limelight entirely. Their strategy: Say nothing at all.