Intel, the venerable microchip maker, is a company built around mining an almost infinite resource: increasingly powerful, increasingly cheap computing power. In 2017, computers and smart devices are ubiquitous, and it’s been 26 years since the company launched its “Intel Inside” campaign to sell people on computer guts. How can an aging tech giant try and stay relevant?

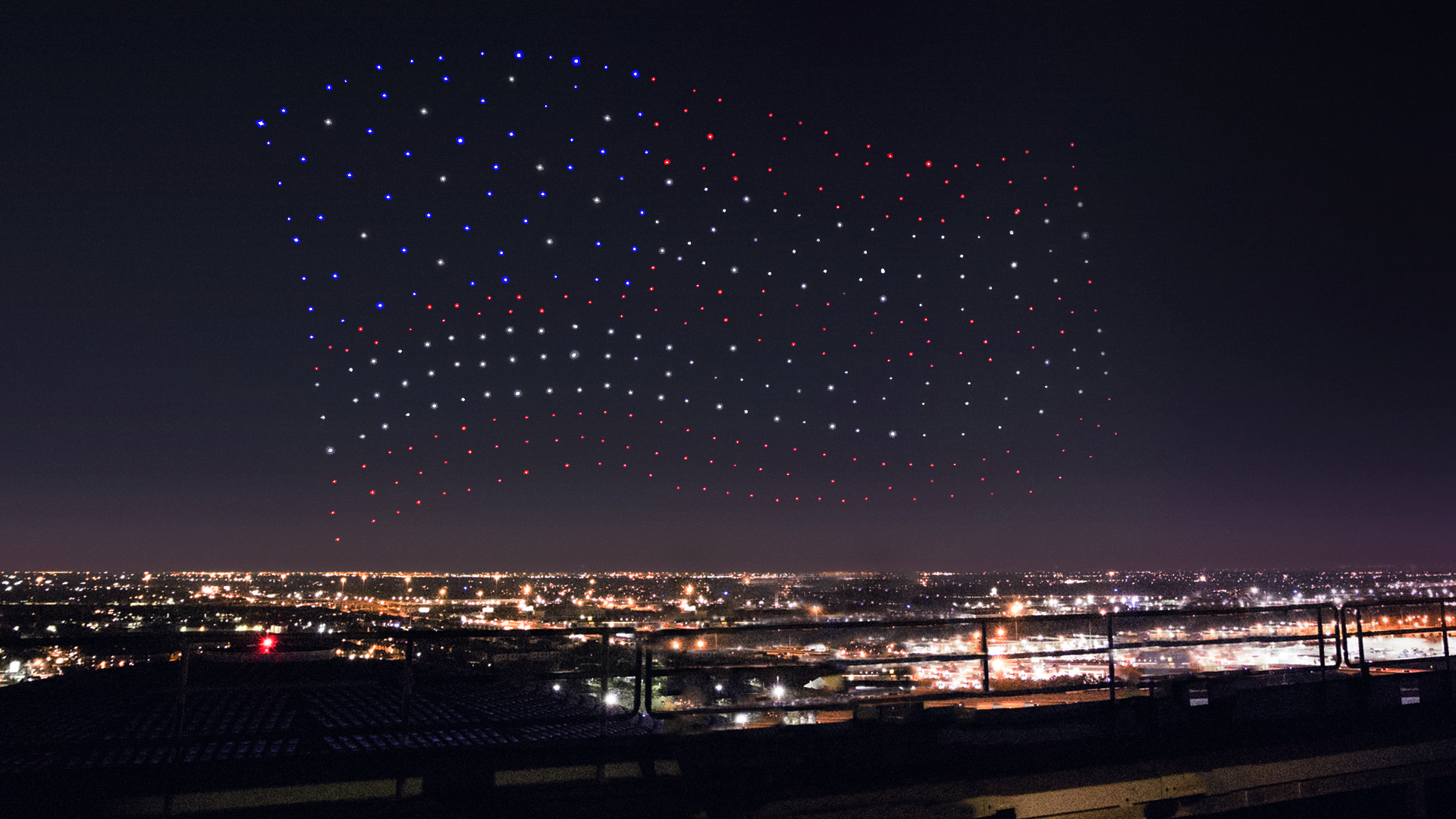

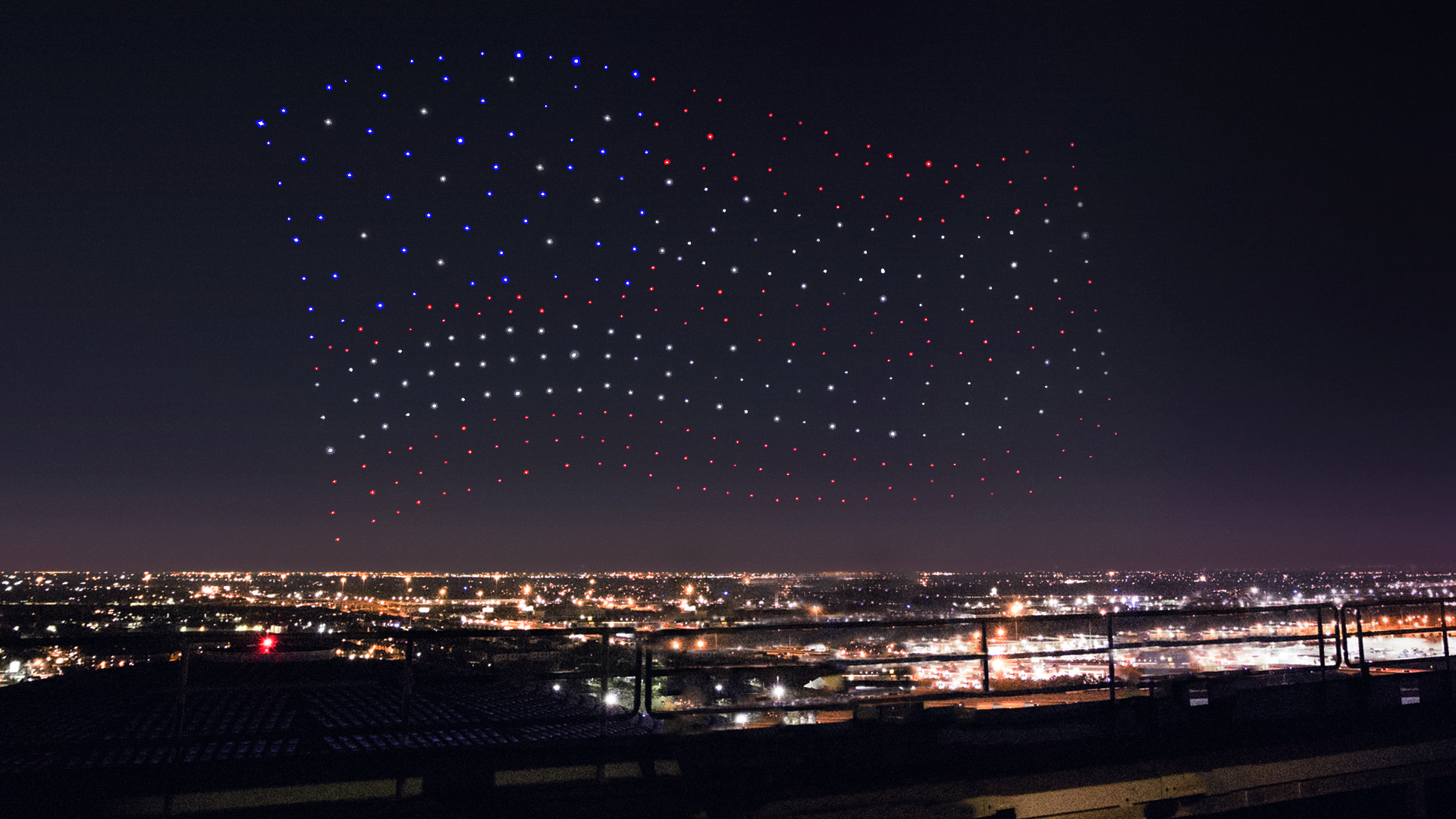

Drones, pop stars, and the biggest advertising night of the year. As Lady Gaga opened the halftime show at Super Bowl LI, she did so in front of a Houston sky, artificially lit by Intel’s drone swarm.

This artful drone swarm is not the first, though it is probably the highest-profile spectacle of its kind in the United States. Drones and dance troupes appeared on talent shows, drones have danced with humans alone in a field, an earlier Intel drone swarm set an early Guinness World Record with a dancing display. And there is my personal favorite, a small swarm of just 20 aerial robots performing before Mount Fuji, lights and flights creating a vibrant, thick sky.

At the end of their Half Time performance, Intel’s drones spelled out the name of the show’s other big sponsor, Pepsi.

Technology repeats itself, first as art and then as advertising. When computers are ubiquitous, the need to showcase their potential in new and novel ways leads to such things as the specially-designed robotic entertainers. Each one of Intel’s “Shooting Star Drones” weighs under 10 ounces, can fly for up to 20 minutes, and flies at around 6 mph. Yet it’s the computing that really stands out: the whole swarm of 300 flying robots are controlled by one pilot and one computer, with a second pilot on hand in case of emergencies.

Coordinating flying swarms has applications far beyond just entertainment. Revealed in a 60 Minutes segment in early January, the Pentagon tested an autonomous drone swarm in October 2016. Those robots, coordinating with each other and flying together towards set objectives, represent the first wave of military swarming, with smaller, cheaper flocks of robots replacing or complementing the jobs previously done by bigger, more expensive craft.

For a swarm to work, each drone in the swarm needs enough computing power to keep track of where it is relative to its neighbors, and to communicate that location, while also flying together in a present plan and accounting for how wind may push them off course. It’s a delicate dance, and one only really possible because of advances in modern computing.

How do you sell a microchip to a world where everyone has computers in their pockets? Cover it in lights, put it in the sky, and show people something they’ve most likely never seen: a brightly colored swarm, hung in the sky like a light-up pinboard.