Amazon’s biggest problem is that it can’t teleport products into the homes of customers. As the largest online retailer, the company struggles with the “last mile problem,” or the difficulty of moving goods that final distance between a hyper-efficient warehouse and the eager customer’s front steps. To help solve this issue, the company has famously been working on drones to make the final drops.

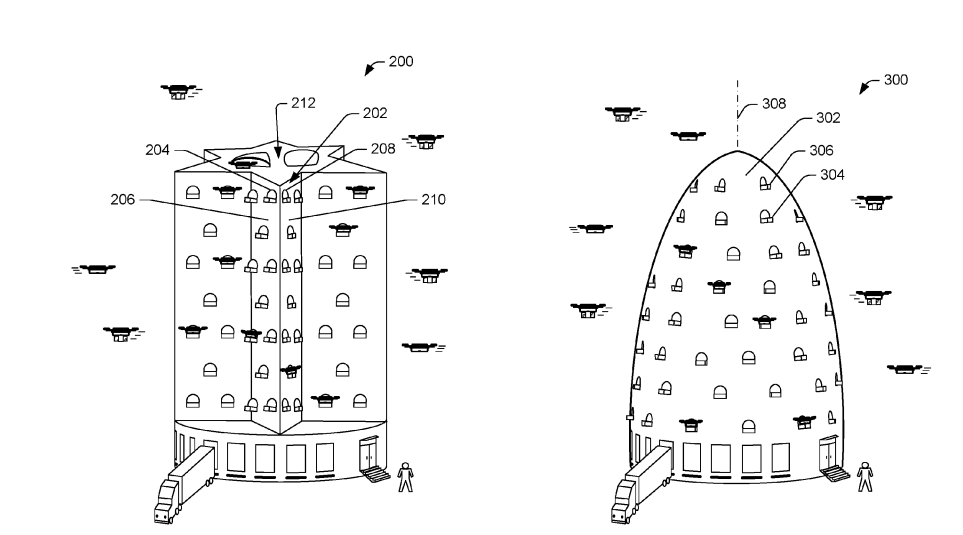

It still sounds like science fiction, but Amazon’s drone delivery program is actually deep into testing, and it is built like infrastructure, to accommodate the instantaneous demands of a massive population, where it can. Along with the testing, Amazon has filed several drone-related patents, including a concept for recharging stations mounted on streetlights, and a distribution center contained within an airship. The latest patent depicts a hive-like tower that houses and launches delivery drones throughout a dense city.

The concept is fantastical: Tall yet compact structures brimming with windows, and from those windows robots merrily delivering packages. Some are boxy towers, others fanciful hive-shapes. All are framed as a hedge against zoning laws, a way to put a high-density warehouse in the middle of a city, for fast delivery directly to customers.

“Fulfillment centers are typically large-volume single-floor warehouse buildings used to temporarily store items prior to shipment to customers,” reads the patent, “Often, due to their large footprint, these buildings are located on the outskirts of cities where space is available to accommodate these large buildings. These locations are not convenience for deliveries into cities where an ever-increasing number of people live. Thus, there is a growing need and desire to locate fulfillment centers within cities, such as in downtown districts and densely populated parts of the cities.”

It’s ambitious and clever, if not completely novel, but it poses some specific challenges in terms of urban infrastructure.

The large size is one reason why most full-scale warehouses are located outside of city centers (and, in the case of New York City, completely outside the city). When loading and unloading lots of goods, it makes sense to do it on one flat level where possible, and even more than that, it makes sense to have a warehouse from which large trucks can easily load and unload full shipping containers. That requires large parking lots, and the space to maneuver multiple 18-wheelers. It’s hard to do downtown anywhere, yet all of Amazon’s drone tower renderings show the towers accommodating big rigs.

“It seems like Amazon has patented the idea of a multi-story warehouse with windows,” says New York-based urban planner Neil Freeman, “And the multi-story warehouse is a building type that has been around for a really long time. They are all over SoHo and lower Manhattan, and now they are used for loft living. They got turned into houses, because they were no longer economical to use for warehousing.”

One big reason for that shift was the economics of shipping put warehouses and distribution centers outside of dense cities. The closest full-scale Amazon fulfillment centers to New York City are located in Teterboro and Woodbridge New Jersey, just off highway exits. It’s at those centers that the big trucks unload their cargo and then Amazon loads them onto smaller vehicles, that can better navigate city traffic. There are two exceptions to this: one is a new 975,000-square-foot warehouse in Staten Island, built on the site that was once considered from a NASCAR track. While within the city limits, it’s hardly the dense location the patent envisions for delivery by drone swarm. The other is a converted floor of a midtown Manhattan building, which can promise deliveries within an hour for a premium fee, and deliveries within two hours for prime members within range.

It’s this “instant delivery as a premium service” that is most likely the impetus behind Amazon’s drone tower. Here Amazon plans to compete with not just regular retail, but small couriers on bicycles and on foot. Still, it’s hard to tell if the drone tower is an actual way to reach that goal. In dense cities like New York, resupplying the warehouse with large trucks is an obstacle, and in places less dense than Manhattan—even Staten Island—large one-story warehouses are still the more-economical bet.

This is to say nothing of the regulatory hurdles facing drones themselves, which are required to fly below 400 feet, and more than five miles away from an airport. In addition, there are flight restrictions, like no-fly zones over power plants or helipads, that drone pilots are supposed to follow. All of lower Manhattan is under at least one permanent flight restriction, and Amazon’s Manhattan warehouse itself sits under the current presidential exclusion zone, which keeps the sky clear around Trump Tower.

There are still hard limits to what drones can carry, how they can operate, and places where it makes economic sense to do so. If Amazon can find another way to resupply its multi-story warehouses, free from the traffic-snarled frustrations of large trucks, and if cities can adapt zoning and public standards to accommodate a constant buzzing of delivery robots, then maybe the drone towers start to make sense as a delivery node. Until then, they are strictly the realm of fiction.